Courrier des statistiques N7 - 2022

The challenge of developing a statistical classification of crimes

France lacked a statistical nomenclature of offences common to all those involved in criminal statistics; the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice used different nomenclatures for dissemination, which prevented the availability of fine-grained statistics that were consistent throughout the criminal justice system. The development of an international nomenclature by the UN in 2015 provided the opportunity to launch this project in France, which was completed in spring 2021.

In order to overcome the differences in criminal legislation, an approach based mainly on the behaviour of the offender has been adopted. Based on a very detailed pre-existing legal nomenclature, an inter ministerial working group has built the French Nomenclature of Offences over a period of five years: the NFI is thus linked to the international nomenclature for the main categories, but with a more relevant detail in the French context. This new tool will make it possible to finally have fine statistics that are comparable between the two ministries and, moreover, that can be compared internationally.

- Incomplete crime statistics

- Box 1. The criminal justice system, from the offence to the execution of the sentence

- Box 2. Criminal statistics are a reflection of criminal activity in society

- The challenge of an international classification

- A possible hierarchy between sections

- The French version of the international classification

- Five years to define a new classification

- A resulting hybrid classification

- Box 3. The first two levels of the French classification of crime

- Titles adapted to the national context

- The limitations inherited from the international classification

- Use that complements other approaches

- A tool that needs to be calibrated through use

- A step towards expanding the coverage of quantitative analyses

Incomplete crime statistics

Crime statistics are one of the oldest forms of statistics: the first regular statistics in France were disseminated from 1827 in the form of a “general account of the administration of criminal justice” (Perrot, 1976). These statistics attracted widespread interest from sociologists, as they cast a light on the moral health of the country; this is the beginning of criminology.

However, interest in these “moral statistics” would then fall and little progress would be made in this area, with the statistics continuing to be based on administrative sources; the statistics of the Ministry of Justice would go on to be supplemented, then largely replaced in the 1960s, by statistics from the Police and the Gendarmes, which identify crime further upstream.

However, this administrative source-based approach has its limits. Such sources are based on legal rather than analytical categories and they also reflect the activity of the services fighting crime: with a constant level of crime, strengthening checks regarding the use of drugs or road traffic automatically increases the number of crimes.

It was not until the 1990s that so-called victimisation statistical surveys were introduced, drawing on Anglo-Saxon examples (Chambaz, 2018; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEstival and Filatriau, 2019). There was then a source available that measured crime experienced without the use of administrative statistics: international comparisons became possible, but these remained limited to the major categories of the victimisation surveys and did not cover all serious and intermediate crimes. These crimes are understood in great detail in the sources from the Ministry of Justice and the Police, but with different “area” classifications (Box 1 and Box 2).

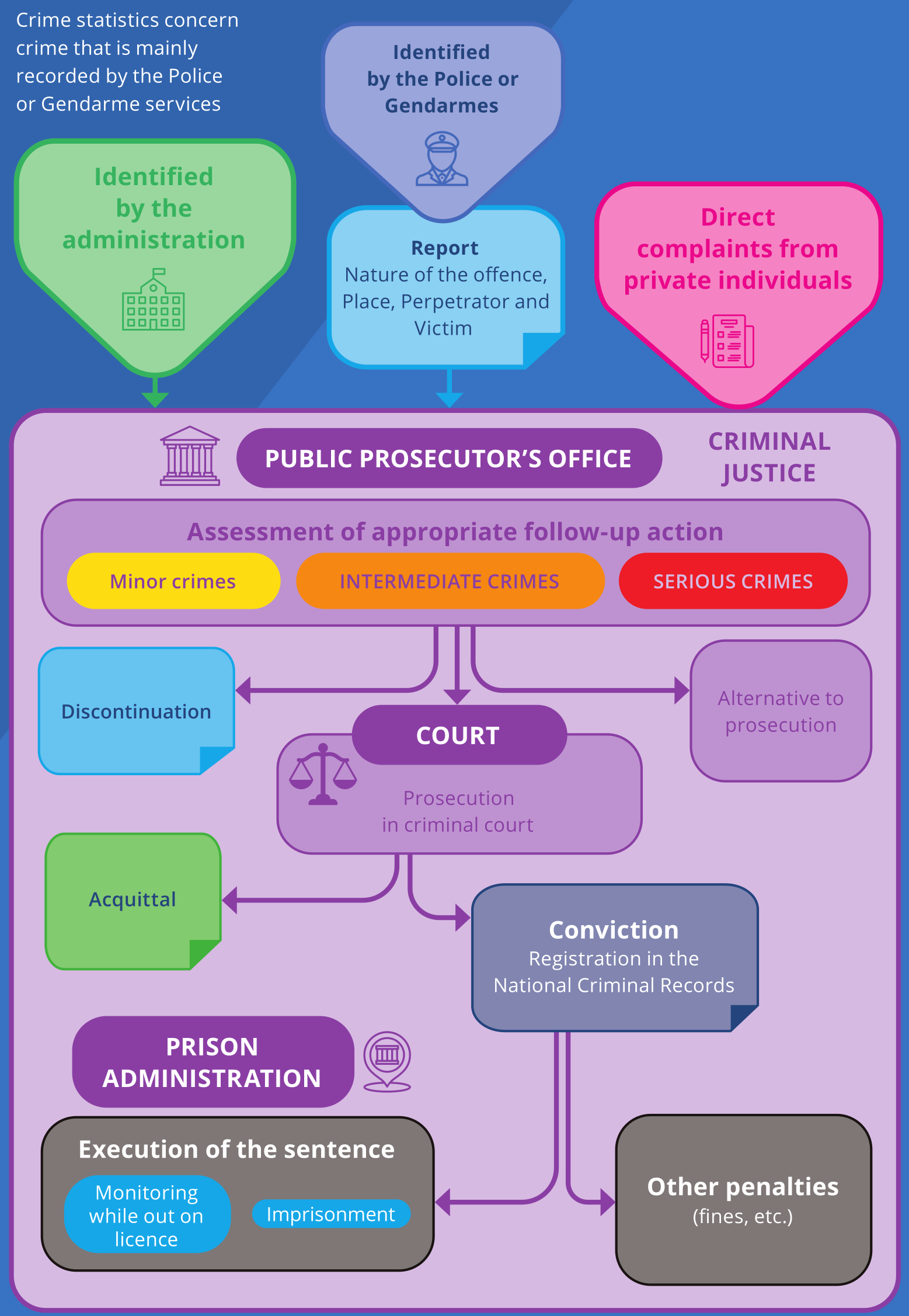

Box 1. The criminal justice system, from the offence to the execution of the sentence

Crime statistics relate to infringements of penal laws and therefore to a legal area that is often referred to as crime. It corresponds to the notion of crime recorded mainly by the Police, Gendarme or Justice services and therefore to administrative statistics.

In simple terms, a crime is most often first identified by a Police or Gendarme service. It is then the subject of a report describing its characteristics: the nature of the crime, location, perpetrator if known, any victims, etc.

This report is then sent to the Justice services by means of a criminal justice system involving the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice for addressing crime.

Criminal justice aims to punish offenders. Depending on the severity of the crime, the channels and the penalties are different:

- the most serious offences, classed as serious crimes (homicides, rapes, etc.) are punishable by imprisonment of ten years or more;

- the least serious offences, classed as minor crimes (speeding, excessive noise at night, hunting without a licence, minor assaults and injuries, etc.) are punishable by fines;

- medium-level offences, classed as intermediate crimes, are punishable by imprisonment of less than ten years.

The first level of the criminal procedure in France is that of the Public Prosecutor’s Office (ministère public), also known as the Parquet in French, which receives the reports of the judicial police officers, mainly from the Police and the Gendarmes, but also from various administrations, and sometimes direct complaints from private individuals.

The Public Prosecutor’s Office assesses the appropriate follow-up action: discontinued (no known perpetrator, no legally constituted offence, insufficient charges, etc.), alternative to prosecution (reminders of the law, compensation, etc.) or prosecution in a criminal court, which may acquit or convict; these convictions are then recorded in the national criminal records.

The execution of the sentence may lead to imprisonment in case of a prison sentence or to monitoring while out on licence (electronic tag, etc.) as part of the prison administration (Figure 1).

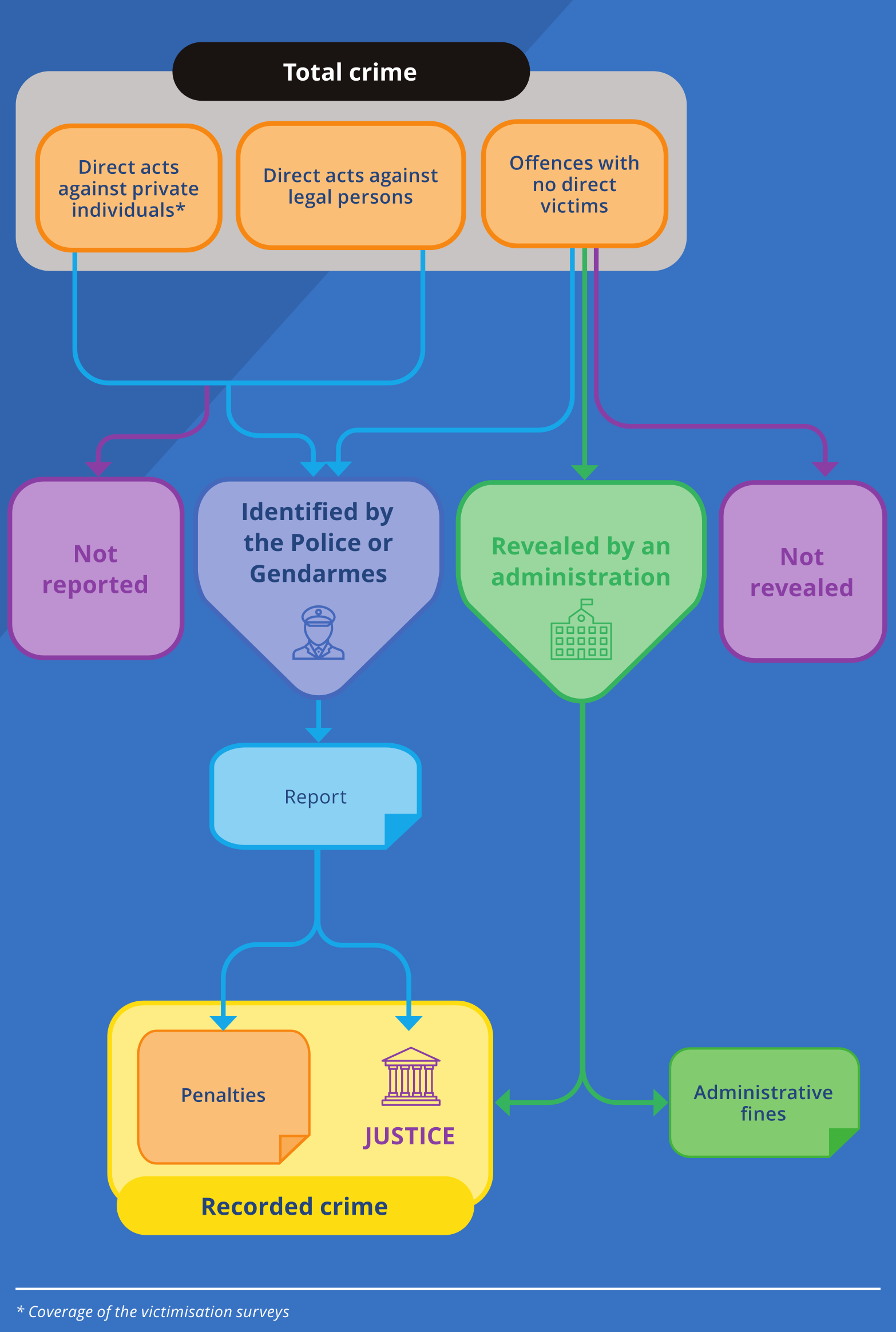

Box 2. Criminal statistics are a reflection of criminal activity in society

First and foremost, these are management statistics. They measure the activity of the security and justice services, which is crucial for these essential government functions: these statistics help to justify the resources requested by the Ministries of the Interior and Justice, are used for the allocation of resources among the many local units (police stations, courts, etc.) and make it possible to measure the effectiveness of the services; they provide information on criminal policy by quantifying the impact, efficiency and effectiveness of many criminal laws; they could also support forecasting work on the flows of cases and offenders through the criminal justice system so as to adapt the security/justice system.

Next, crime statistics measure recorded crime. Crime statistics provide a deformed and truncated view of reality, as though through a prism, as only recorded crime of a certain level of severity is observed.

Since the 1970s, the Police and Gendarme services have released monthly indicators, akin to statistical bulletins on the crimes detected or on the future evolution of crime as far ahead as possible in the criminal justice system. These data are now finely localised and allow for the mapping of crime by type. Subsequently, the Justice service publishes statistics in accordance with the stages of judicial processing: cases sent, follow-up given, judgments handed down, convictions, incarceration or monitoring while out on licence. This measurement of crime has known biases: it concerns only crime recorded by the Police and the Gendarmes and crime suffered but not reported is only identified by victimisation surveys (which cover only part of the crime, that involving individual direct victims); this measurement also depends on the activity of the security forces. However, this measurement is very valuable: it allows the observation of cyclical trends in crime and makes it possible to very precisely determine the type of crime and the profile of the perpetrators, especially if they are first offenders or repeat offenders. This results in fruitful analyses of recidivism, which can be seen as an indicator of the effectiveness of the criminal justice system and which is at the heart of the analysis of crime.

While the main economic and socio-economic areas have regularly updated classifications (Amossé, 2020; INSEE, 2008; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGuibert, Laganier and Volle, 1971), crime statistics lacked the thing that forms the foundation of any statistical work: a statistical classification that is broadly shared among all stakeholders.

In practice, the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice had developed very detailed but incompatible classifications, which resulted in the recurrent dissemination of inconsistent crime figures, with statisticians having to regularly explain the reasons for the counting discrepancies. However, deep down, it is a case of tracking the same element: the penal processing of a crime, from detection through to the penal response by the Justice system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. From the offence to the execution of the sentence: the criminal justice system simplified

With the digitisation of the National Criminal Records system in the 1980s, the Ministry of Justice implemented a granular coding of crimes called NATINF (named for the nature of a

crime – NATure d’INFraction in French); this management classification is intended to assign a numerical code

for each crime created by the law. The NATINF is truly highly detailed: under the

legislation in force, it covers around 900 serious crimes, 9100 intermediate crimes

and 7000 minor crimes. For several years now, this classification has also been applied

in the software used by the Police and Gendarmes and it is thus included in all the

applications of the criminal justice system (Police, Gendarmes and the Ministry of

Justice). This common management classification contained the first basis for the

possibility of producing statistics that are comparable across the Ministry of the

Interior and the Ministry of Justice.

The creation of the Ministerial Statistical Office for Internal Security in 2014 contributed to the production of statistics on crime classes shared by the two Ministries. Methodological work has been carried out in conjunction with the Ministerial Statistical Office for Justice and the Directorate of Criminal Affairs and Pardons to reconcile data from the services in the legal field of drugs (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletClanché, Chambaz et al., 2016) as well as on the issue of domestic violence (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBrunin, Guedj and Le Rhun, 2019).

In addition, in response to certain institutional requests, these services held discussions in order to have common crime areas, for example for gender-based attacks (High Council on Gender Equality [Haut Conseil à l’égalité entre les femmes et les hommes]), racist, xenophobic or anti-religious attacks (National Advisory Commission on Human Rights [Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme], National Institute for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights [Institution nationale de protection et de promotion des droits de l’homme]) or money laundering and terrorist financing (Financial Action Task Force [Groupe d’action financière]). However, the aim of this ad-hoc work was not to create a genuine classification aimed at covering all legal areas.

The challenge of an international classification

In 2009, the UN set up a dedicated team to develop a classification of crimes. Its work culminated in 2015 with the approval of an International Classification of Crimes for Statistical Purposes (ICCS) by the UNODC, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletUNODC, 2015).

A crime is an assault on society’s values, but it is the law that sets out the unacceptable deviations from these values, hence the ICCS’s operational definition: crimes are “behaviours which are defined as criminal offences and are punishable as such by law. The offences defined as criminal are established by each country’s legal system”.

The problem is that countries’ criminal law systems are very diverse: Roman law in Latin European countries, Anglo-Saxon common law, Islamic law, Chinese law, etc. To overcome differences in criminal legislation, the ICCS adopted an approach based primarily on the behaviour of the perpetrator of a crime. As regards its terminology, the classification is based on the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as on many international UN conventions to fight crime (drug trafficking, human trafficking, money laundering, terrorism, organised crime, etc.) and sometimes on other international texts (e.g. a European directive on insider trading). These aspects of international law make it possible to overcome the problem posed by the existence of very different criminal law systems.

In order to create the ICCS, priority was given to criteria of particular interest to crime prevention and criminal justice policies. Then there are the criteria:

- relating to the target (person, object, natural environment, State, etc.), which corresponds to the French concept of protected interests;

- relating to severity (act that resulted in death, etc.)

- or relating to the methods used (with violence, etc.).

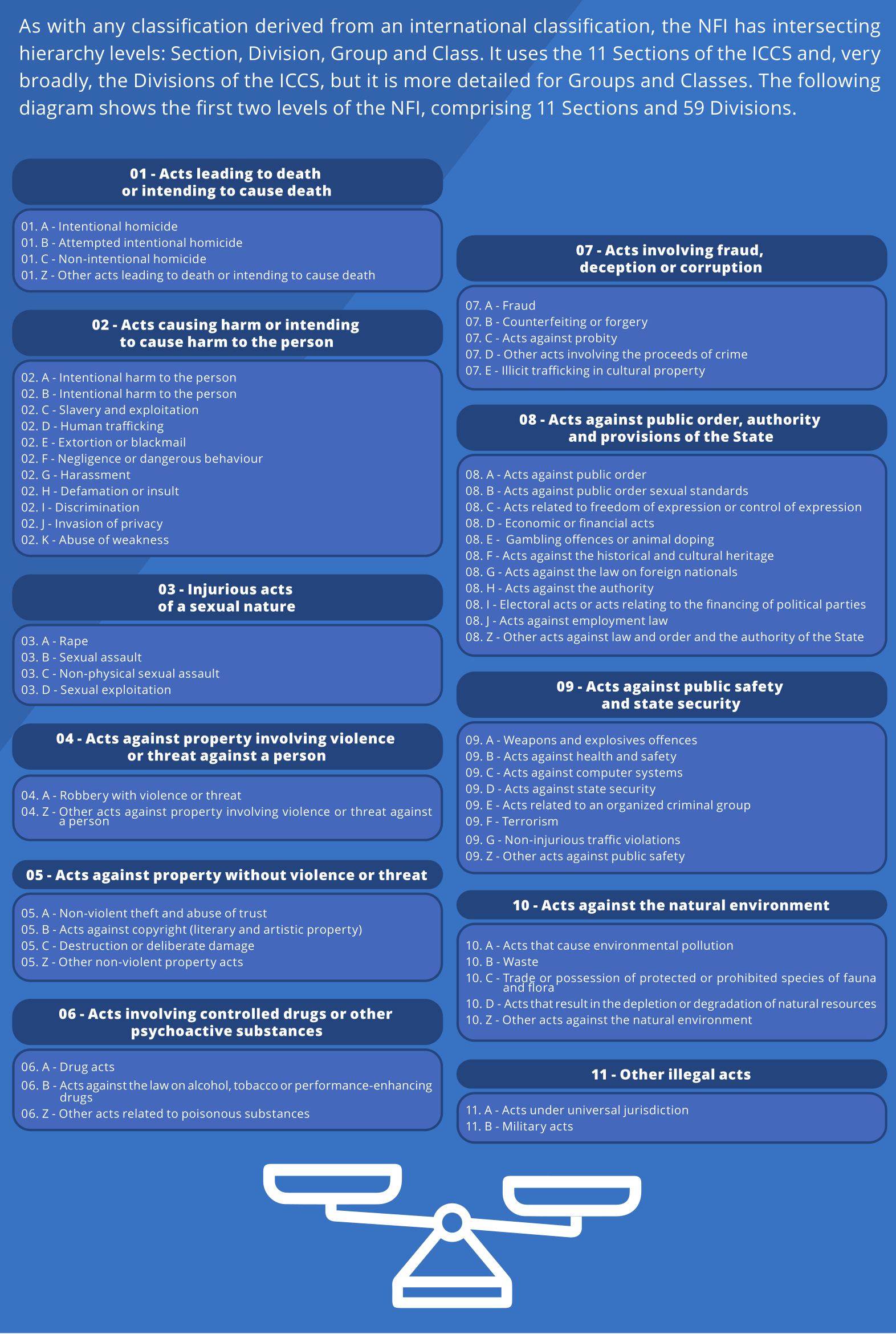

The international classification consists of 11 sections with a breakdown by major domains and a potential hierarchy in the order of sections (Figure 2):

- first, all acts leading to death or intending to cause death (Section 01);

- then all acts causing harm or intending to cause harm to the person (Section 02);

- separating injurious acts of a sexual nature (Section 03);

- then acts against property, making a distinction for acts involving violence or threat against a person (Section 04);

- and acts against property only (Section 05);

- and finally, acts against society (Sections 06 to 10): drugs (06), fraud (07), acts against public order (08), acts against public safety (09) and, finally, acts against the natural environment (10);

- the remaining Section 11 essentially includes acts under universal jurisdiction (such as crimes against humanity).

Figure 2. The same first level for the French classification (NFI) and the international classification (ICCS)

It is understood that the first sections correspond to well-defined areas of traditional

crime and that the later sections relate to attacks on society the definition of which

changes more over time and varies in space; for example, cybercrime, which was unknown

decades ago, or attacks against public morality (decriminalisation of homosexuality

that is uneven across countries).

A possible hierarchy between sections

All acts leading to the death of a person are grouped together under Section 01 (except crimes against humanity): for example, rape followed by death is classified in Section 01 and not in Section 03 “Injurious acts of a sexual nature”; death following a terrorist act is also classified in Section 01, not Section 09, “Acts against public security and state security”.

Another peculiarity is that, in order to cover the entire international scope of crimes, the classification includes crimes that correspond to acts that are legal in some countries and illegal in others, or even against human rights (apostasy, proselytism, abortion, adultery or homosexuality, for example). However, these situations concern only a very limited number of items, resulting in marginal impact on international comparisons.

The French version of the international classification

It was INSEE’s responsibility to coordinate the adaptation and implementation of the ICCS in the French Official Statistics system, in order to make the latter the reference framework for the production and dissemination of Official Statistics in all areas of security and criminal justice.

To that end, an inter-ministerial working group involving the main stakeholders concerned was established in 2016. The working group was to carry out a dual-purpose project: to complete the ICCS items as well as possible and to define a national version that is linked with the ICCS and relevant in France. This work was also intended to determine an aggregated statistical classification common to the Ministries of the Interior and Justice, which did not yet exist. At the end of a cycle of 34 meetings, the working group thus proposed an initial version of the French Classification of Crimes (Nomenclature française des infractions – NFI) in April 2021.

The difficulty of the exercise was to make a clean break with the old classifications and create a common classification. In fact, the stakeholders involved performed well, probably because the ICCS offered a highly structured framework that was missing in the area classifications usually developed over time without any statistical purpose. The investigation work carried out to define the ICCS was of high quality. As evidence of this, as early as 2016, American academic experts recognised that the ICCS had all the qualities expected of a classification of crimes and thus proposed to adopt it as a central framework for a classification in the United States, with some adjustments to take the national context into account (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletNASEM, 2016).

In terms of coverage, a 2019 ICCS implementation manual (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletUNODC, 2019) recommends that countries using Roman law limit themselves to the most serious offences (serious crimes and intermediate crimes). However, the working group chose a broader option, adding minor crimes, as the boundary between serious crimes and intermediate crimes and minor crimes varies over time (example of driving without a licence) and, as a result, this broad coverage most often corresponds to the coverage of the statistics currently disseminated by the Ministries of the Interior and Justice in France (Figure 3). International comparisons will only be possible in the area of serious and intermediate crimes.

Figure 3. From total crime to recorded crime

Five years to define a new classification

A first step was to establish a table for switching from the NATINF to the ICCS. DACG experts therefore needed to analyse some 17,000 basic items in the NATINF used in the applications of the criminal justice system. This advance work is recommended by the UN and Eurostat (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEurostat, 2017) and it was followed in particular by German statisticians (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBaumann, Kerner and Mischkowitz, 2016). This is complex and thorough work that requires many choices with gradual refinements as the different sections are examined, which explains the duration of the working group.

The assignment of a specific crime to an ICCS item has often posed boundary problems. The working group sought to identify the main area of the crime in order to form homogeneous categories. For example, French environmental law involves many crimes that are preventive: they have been assigned in Section 10 “Acts against the natural environment,” not Section 08 “Acts against public order, authority and provisions of the State”, because the main protected social value here is the environment, thereby bringing together all environmental offences in one place.

Another assignment criterion is assignment to the most precise item. For example, tax fraud is separated in Section 08 in Item 08041 “Acts against public revenue provisions” and not in a more general item in Section 07 “Financial fraud against the State” (070111), whereas the ICCS’s inclusions/exclusions were contradictory in this regard.

The NATINF legal classification does not fully describe behaviour; for example, crimes of “theft with aggravating circumstances” may not reveal certain characteristics of the behaviour: the victim’s status, the place of offence, the nature of the property stolen, etc. That is why, beyond NATINF, other management variables such as the “index” (dissemination category) coding of the Ministry of the Interior or the nature of “aggravating circumstances” for the Ministry of Justice sometimes needed to be used, for example, to distinguish between theft with or without violence.

A resulting hybrid classification

Starting from the NATINF/ICCS switching table, the French classification of crimes was linked with the ICCS and adapted to the French context. A hybrid nomenclature, blending an international statistical version and granular coding of criminal legislation, has been constructed.

The granular nature of the NATINF/ICCS switching table essentially sets the levels used for the French classification. The degree of overlap between the two classifications differs depending on the sections. The breakdown into sections and divisions used by the ICCS has been retained almost systematically (11 first levels and 62 second levels). Within the divisions, one sought to stay as close as possible to the ICCS sub-divisions; when this was no longer possible, a simple breakdown was introduced with categories of acts that were well separated and of importance in France, so as to ensure a statistical classification of crimes relevant to the country. For example, for Section 10 (acts against the natural environment), the French classification of crimes uses the sub-divisions of the ICCS, while making them more detailed for the extra item “other acts against the natural environment”, by adding 8 sub-divisions to make a distinction for the area of preventive acts (Box 3).

This approach is similar to that of the United States, which in 2016 defined a statistical classification of crimes using the 11 divisions of the ICCS, but restructured breakdowns from the division level (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletNASEM, 2016). For example, in Section 02, rather than making a distinction between serious assault and minor assault, the Americans separate violence into violence with and without firearms. Generally speaking, the NFI deviates from the sub-divisions of the ICCS much less than the American classification.

Titles adapted to the national context

The titles of the French classification use those of the French version of the ICCS, except to take into account the practices of the identification of crimes and of French criminal law in order to produce more understandable titles in France. Many of the titles have thus been amended compared to those of the French version of the ICCS: “legal person” rather than “legal entity”; “robbery with violence or threats against a person” rather than “robbery”; “harassment” rather than “acts intended to induce fear or emotional distress.”

The work to create the NFI was carried out based on the NATINF, but other information was sometimes used. As discussed previously, some of the criteria used by the ICCS are sometimes not included in the title of the NATINF, but are accessible in other variables describing the criminal acts and available in criminal justice system files (for example, the age of the victim, to identify acts against minors, “aggravating circumstances”, the “index” of Police or Gendarme records). The introduction of the NFI takes this possibility of more granular coding of certain segments of the criminal justice system into account. One parallel can be made with the classification of “Professions and Socioprofessional Categories” (Professions et Catégories Socioprofessionnelles – PCS) which can be coded at a different level depending on whether the statistical sources are “employer” or “employee” sources. For example, only the use of the “index” variable in Police/Gendarme sources makes it possible to make a distinction between robbery with violence involving a person, in a public place, in a private place, in a financial institution or in a non-financial institution.

The limitations inherited from the international classification

The ICCS is an international classification that focuses on areas of international crime which have been the subject of agreements, such as drugs, intellectual property or organised crime. In contrast, areas with a local dimension or those in which criminal law is less developed are less well covered. Thus, the accompanying manual does not refer to infringements of town planning or construction law, nor to infringements related to means of transport other than road traffic (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletUNODC, 2015).

In defining the NFI, therefore, efforts were made to overcome this limitation by adding sub-divisions that supplement the UNODC classification approach. As a result, some precautions will be necessary for its use, particularly when making international comparisons.

The areas covered by the first five sections are relatively easy to identify: acts against people and property. The same cannot be said in respect of acts against society. Although the areas covered by Sections 06 (Acts involving controlled drugs or other psychoactive substances) and 10 (Acts against the natural environment) are well delineated, there are possible overlaps between Sections 07 (Acts involving fraud, deception or corruption), 08 (Acts against public order, authority and provisions of the State) and 09 (Acts against public safety and state security). For example, illegally practising a profession may be related to ICCS item 07019 (Other acts of fraud) or item 08042 (Acts against commercial or financial regulations) or even item 02071 (Acts that endanger health) in the case of illegally practising medicine.

When making international comparisons, it is important to recognise that legislation may sometimes differ significantly. There are areas where comparisons can be made without particular difficulty, such as homicides or attempted homicide, and other areas, such as drug use, where criminal legislation can diverge greatly. In practice, a large proportion of the crimes fall into the former areas.

Use that complements other approaches

Finally, as with any classification, the assignment of a crime to one and only one category is reductive and does not allow for certain national analysis needs. Certain crimes could be related to two categories; this difficulty was encountered when developing the NFI. The categories for which a dual approach may be possible could be separated. A theoretical optimal solution would have been to use a sufficiently detailed NFI to allow this dual approach. For example, while rapes followed by death were separated in the NFI, the aggregated number could be calculated for all rapes (with or without death). However, the systematic application of this approach would be very costly (due to the multiplication of granular NFI items with low numbers), meaning that it has rarely been used. For example, counterfeit goods that are dangerous to health are classed as unsafe acts in Section 02 so that they can be aggregated with all counterfeit goods that are classified elsewhere in Section 07 (Acts involving fraud, deception or corruption).

In order to address cross-cutting issues (such as organised crime), it will therefore be necessary to move away from the NFI and use the groupings of the NATINF. The best way to overcome this limitation is to add “additional descriptors” for each crime, as recommended in the ICCS manual; such an expansion requires a lot of work that could be organised in the future to ensure greater flexibility in the use of the classification, as the Americans have done (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletNASEM, 2016).

A tool that needs to be calibrated through use

The next step is to begin use of this initial version of the NFI to test its relevance and robustness. Only analyses by type of crime will show the most relevant aggregation levels. It will also be necessary to study possible backcasting and to document any series breaks. The linking of the NFI with the ICCS will facilitate responses to international crime questionnaires and will make it possible, in particular, to provide information on some of the UN’s sustainable development indicators, mainly those associated with the 16th goal “Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions” (Clanché, 2019).

This exercise to define a national classification also allows for a critical feedback to UNODC, with a view to the future revision of the ICCS. For example, the division of acts against society (Sections 07 to 10) between the various headings is yet to be clarified by location. In Section 07, the first division 701 (Financial fraud against the State) has a misleading title, as it excludes tax fraud. Similarly, it should be noted that there are strong overlaps between the items in Section 08 and 09. Sometimes the level of detail is excessive: in Section 01, the items of interest are the first three divisions and the next five are there only to isolate certain types of homicides that are not very comparable between countries or for which there are low figures; it would be beneficial to group them together into a single division (Other acts leading to death or intending to cause death) as was done in the NFI. The development of the NFI led to the creation of 30% more items than the ICCS; the UN could consider whether or not these additions are of interest in a broader context.

A step towards expanding the coverage of quantitative analyses

Thus, this classification marks a decisive step in the quantitative approach to crime, by expanding and structuring the coverage of studies. In particular, analyses into areas of crime still not well covered could be enriched: areas such as economic and financial crime, cybercrime, the environment, etc.

In conclusion, let’s hope that this classification encourages the development of quantitative studies on crime in the broad sense (serious, intermediate and minor crimes). The field remains poorly studied, although the statistical sources of the Ministries of the Interior and of Justice have now become very rich and usable in common categories: this was legitimately expected by parliamentarians, the media and the general public. Finally, these categories allow international comparisons that put the French figures into perspective.

Paru le :19/02/2024

More specifically, the Criminal Policy Evaluation Unit of the Directorate of Criminal Affairs and Pardons (Direction des affaires criminelles et des grâces – DACG).

In its final composition determined in 2018, this group included the Ministerial Statistical Office for Internal Security (Service statistique ministériel de la Sécurité intérieure – SSMSI) of the Ministry of the Interior, the Sub-Directorate for Statistics for Studies (Sous-direction de la Statistique des études – SDSE), the Ministerial Statistical Office for Justice, the Criminal Policy Evaluation Unit (Pôle d’évaluation des politiques pénales – PEPP) of the Directorate of Criminal Affairs and Pardons (Direction des Affaires criminelles et des grâces – DACG) of the Ministry of Justice, representatives of the operational services of the Ministry of the Interior (Directorate-General of National Police [Direction générale de la Police nationale] and Directorate General of the National Gendarmerie [Direction générale de la Gendarmerie nationale]).

The final version was published online on 2 December 2021 (Ministry of the Interior, 2021).

Minor crimes represent a significant part of the crimes perpetrated in certain areas: consumption, the environment, road traffic and acts against public order.

In force or repealed.

Pour en savoir plus

AMOSSÉ, Thomas, 2020. La nomenclature socioprofessionnelle 2020 : Continuité et innovation, pour des usages renforcés. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 29 June 2020. Insee. N°N4, pp. 62-80. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

BAUMANN, Thomas, KERNER, Hans-Jürgen et MISCHKOWITZ, Robert, 2016. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletNational Implementation of the new International Classification of Crimes for Statistical Purposes (ICCS). In: WISTA – Scientific Journal. [online]. 1er May 2016. Statistisches Bundesamt. N°5-2016, pp. 102 et suivantes. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

BRUNIN, Louise, GUEDJ, Hélène et LE RHUN, Béatrice, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletComparaison des statistiques Sécurité et Justice : Le contentieux des violences conjugales. [online]. November 2019. SSMSI-SDSE-DACG. Interstats Méthode N°16. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

CHAMBAZ, Christine, 2018. De l’activité de la justice au suivi du justiciable, faire parler les données de gestion. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 6 December 2018. Insee. N°N1, pp 45-57. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

CLANCHÉ, François, 2019. La mesure de la sécurité et la satisfaction vis-à-vis des institutions en France, l’impulsion donnée par les objectifs du développement durable des Nations Unies. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 27 June 2019. Insee. N°N2, pp. 33-45. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

CLANCHÉ, François, CHAMBAZ, Christine, LETURCQ, Fabrice, LIXI, Clotilde, MAHUZIER, Ombeline, TURNER, Laure et VIARD-GUILLOT, Louise, 2016. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletPour une méthodologie d’analyse comparée des statistiques Sécurité et Justice : l’exemple des infractions liées aux stupéfiants. [online]. December 2016. SSMSI-SDSE-DACG. Interstats Méthode N°8. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

ESTIVAL, Alexandre et FILATRIAU, Olivier, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLa mesure statistique de la délinquance. In: Dalloz AJ pénal. [online]. April 2019. pp. 224-231. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

EUROSTAT, 2017. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEU guidelines for the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes – ICCS. [online]. Octobre 2017. Manual and Guidelines. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

GUIBERT, Bernard, LAGANIER, Jean et VOLLE, Michel, 1971. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEssai sur les nomenclatures industrielles. In: Économie et Statistique. [online]. February 1971. N°20, pp. 23-36. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

INSEE, 2008. Dossier spécial Nomenclatures. In: Courrier des Statistiques. [online]. November-December 2008. N°125. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

MINISTÈRE DE L’INTÉRIEUR, 2021. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLa nomenclature française des infractions (NFI). [online]. 2 December 2021. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

NASEM, 2016. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletModernizing Crime Statistics: Report 1: Defining and Classifying Crime. [online]. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The National Academies Press. Washington, DC, USA. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

ONUDC, 2015. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletClassification internationale des infractions à des fins statistiques. Version 1.0. [online]. March 2015. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

ONUDC, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletICCS Implementation manual. [online]. Marchs 2019. [Accessed 16 December 2021].

PERROT, Michelle, 1976. Premières mesures des faits sociaux : les débuts de la statistique criminelle en France (1780-1830). In: Pour une histoire de la statistique. Contributions Insee. Economica/Insee, Tome 1, pp. 125-137. ISBN 2-7178-1260-1.