Courrier des statistiques N7 - 2022

The arrangement of mixed-mode surveys

For INSEE, the development of mixed-mode surveys is part of a delicate and rigorous orchestration. Among other things, the aim is to create online questionnaires that are consistent with interviewers’ questionnaires and to coordinate the work of interviewers and managers involved in multiple data collection operations via different methods, all while maintaining smooth and effective implementation taking resource and timing constraints into account. These challenges relating to creation and transformation are themes of the approach implemented by INSEE over the past decade. The pace of this approach is determined by genuinely large-scale implementations relating to survey operations: first with companies and then with households, first via the Internet and then with interviewers, first using simple protocols involving only one collection method and then using complex protocols involving multiple collection operations, via different methods, simultaneously.

Since the launch of this structural evolution for Official Statistics, the same pattern has been applied: first think about the job, express it, design it, then move on to the implementation or scaling up phases. The experience gained at each stage favours the gradual creation of the conceptual and technical tools of “genuinely” mixed-mode surveys, in all their complexity.

- To switch from a single collection method to multiple ones

- “Poly-mode” collection (warm-up stages)

- Box 1. A change in song sheet: from the address sheet to the survey unit

- Conceptualise before implementation

- Business surveys (first symphony)

- Online household surveys (a variation on the same theme)

- Sharing resources without dogmatism (a shared song sheet, risks of dissonance)

- Poly-mode and mixed-mode, the same music?

- Each type of data has its own collection tool (the end of the one-man band)

- The “omni-mode” questionnaire (multiple couplets, a single arrangement)

- The coverage of omni-mode questionnaires (in three octaves)

- The challenges of the mixed-mode process (stakeholders who must act in concert with each other)

- A new concept? The survey unit of interest (a new scope)

- Knowing how to and being able to make yourself heard across collection methods (to avoid the cacophony)

- The different collection methods in unison

- First mono-mode operations (with mixed-mode tones)

- Improving virtuosity by tackling increasingly complex mixed-mode protocols

For many surveys of French Official Statistics, conducted among companies or households, online data collection has been an alternative to paper collection for a few years now. It is also becoming an alternative or supplement to data collection face-to-face or via telephone, thereby creating new, more complicated data collection protocols referred to as “mixed-mode” protocols.

Beyond the tricky statistical or methodological issues raised by the advent of such protocols, it is necessary to examine the operational complexity brought about by mixed-mode protocols, in light of the experience gained.

How does one create a consistent set of tools capable of delivering the expected services? What are the expected services, exactly? How should they be organised? Which stakeholder is responsible for which task? What range of services should be offered? In what order?

The approach is somewhat similar to INSEE writing its score and its arrangements to achieve harmonious mixed-mode collection. Initial solos, single-mode operations, first enabled the Institute to examine the concepts, tools and processes. Then “polyphonic” variations, in which different methods are implemented independently of each other, made it possible to characterise each collection method, which is a preliminary so-called “poly-mode” stage. It is preparing for the implementation of genuine mixed-mode protocols, in which the different collection methods must now act together.

To switch from a single collection method to multiple ones

The development of online data collection, supplementing another collection method, is bound to be accompanied by a set of associated practical questions: how does one construct a web-based survey? Should the same questions be used in the different collection methods? How are respondents contacted? How are they given reminders?

While mixed-mode data collection does raise some complex questions about the quality and usability of the data collected, it is first necessary to find an answer to the question of feasibility: how should a data collection operation involving multiple collection methods, one of which is new, be conducted? A first reflex is to rely on current practices to define the new ones, in an attempt to replicate what has already been done. However, the complexity caused by the new collection method (development of a new questionnaire, the need to manage usernames/passwords, etc.) and its specific features (not always an approach phase by an interviewer, context of less constrained responses, etc.) lead to taking another step in the thought process: to conceptualise what has already been done and what would need to be done.

“Poly-mode” collection (warm-up stages)

The first conceptualisation stage introduced by INSEE, which is easily the oldest stage at present as it has been in place for several years, is the automatic generation of collection instruments (sometimes inaccurately referred to as the generation of questionnaires). It is based on the principle of active metadata (Bonnans, 2019) and starts with the simple premise that a repeated process, in this case the development of a survey questionnaire, often benefits from being automated.

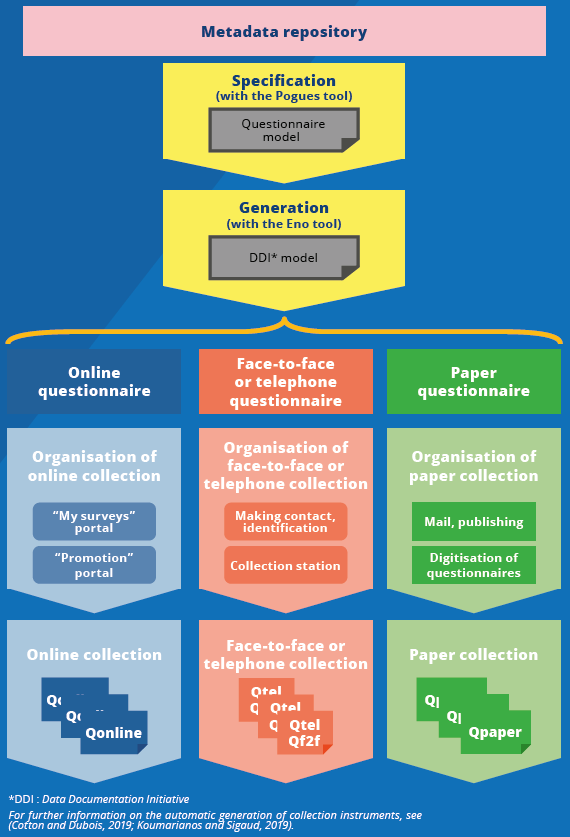

In order to conceptualise a process, i.e. the process of “manufacturing” the questionnaire, the Generic Statistical Business Process Model (GSBPM) is the reference standard in this field. It suggests an initial breakdown into a design phase and a construction phase. During the first phase, the questions are defined, without reference to a specific collection method. During the second phase, the collection instruments dedicated to a specific collection method are constructed. At INSEE, this breakdown provides structure for the tools Pogues and Eno (Cotton and Dubois, 2019; Koumarianos and Sigaud, 2019): Pogues allows the specification of a questionnaire in an application, while Eno supports the generation of collection instruments (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Poly-mode protocols, the first step toward using metadata for collection

This generative approach make it possible to capitalise on best practices across questionnaires

and to implement the functions specific to each method:

- barcodes for paper questionnaires;

- accessibility and functionality across multiple devices (smartphones, tablets, etc.) for online questionnaires;

- adapted navigation and ergonomics for questionnaires administered by an interviewer;

- questions placed in the right format for the collection method (drop-down list for online use/code card for in person use vs open response field for use on paper), etc.

Thus, the production of questionnaires can change in scale, from the ad hoc development of questionnaires specific to each collection method and each survey, to the automated production of collection instruments for several collections methods, relying on the same specification tool and streamlining the development work: formally, ad hoc development work is no longer carried out.

The “single-mode” approach, in which the process and tools are thought out and implemented for a specific collection mode, gives way to a “poly-mode” approach, in which the process and tools are conceptualised to support multiple collection methods and multiple surveys (online, paper, telephone, multiple collection sequences, etc.).

We then understand the full value of the active metadata approach, which allows the automatic generation of questionnaires, and more broadly the “collection instruments” (Koumarianos and Sigaud, 2019). Moreover, the approach is not limited to solely the phases for the design and construction of collection instruments. After these initial phases of the GSBPM, the collection process as a whole can be conceptualised in order to allow its establishment in accordance with the survey, its collection method and its protocol. Thus, metadata such as those resulting from breakdowns into operations (multiple sequences, collection rounds), schedules of collection operations (collection start/end, reminder dates) or protocol characteristics (competitive or sequential, with or without identification phase, with or without re-interviewing) could also be “activated” and enable the monitoring of the processes implemented.

One example of the transformation brought by conceptualisation perfectly illustrates the contribution of this metadata-based approach: the switch from the address sheet (document containing the contact details of a household to be surveyed) to the survey unit (Box 1). The concept of a survey unit refers to the account units of a collection operation, whether the survey is conducted online, by telephone, face-to-face or on paper. In particular, the concept allows data collected via a questionnaire to be linked to the information relating to how the collection was carried out (paradata), regardless of the collection method used.

Box 1. A change in song sheet: from the address sheet to the survey unit

The household surveys of French Official Statistics have long relied on face-to-face collection, which can be seen in the usual name used at INSEE for the “household respondent” item under the term “address sheet”.

An address sheet, in INSEE vocabulary, initially refers to the paper form on which the contact details of a respondent, individual, household or dwelling that an interviewer needs to interview are recorded.

In a mono-mode context, there is a certain degree of joined up logic between the production of these paper documents for interviewers, the drawing of the sample and the configuration of the applications and flows for the implementation of a collection operation. Each time, the information discovered is more or less the same as that recorded on the “address sheets”. Thus, in a distortion of the language, the respondent is also referred to as an “address sheet” and everyone understands what is meant.

However, what happens to this address sheet in the context of collection online or by telephone, when no interviewer visits? Does this paper still need to be printed? What happens to this paper when the telephone details are needed rather than a physical address? How can the information obtained from concurrent online collection be recorded on this paper?

These questions require a preliminary consideration regarding the process (approach or identification, contact/appointment or access to the online questionnaire, retrieval of the collected data, etc.) before the survey can be set out using a new method.

The address sheet then becomes the survey unit and it moves through the different phases of the collection process, from its “birth” in the sample cradles to its “education,” whether under the watchful eye of an interviewer or involved in the more “chaotic” interactions of connected modernity, until its “transition to adulthood,” transformed by processing into statistical variables. The design of this “life cycle of the survey unit” makes it possible to identify the concepts and the events necessary to trace the history of the survey unit. It is then possible to identify items that can be shared within the different systems: contact details, classification of the type of non-response, etc. This clarification of events may be relevant to a particular method (contact or identification attempt for surveys using telephone interviewers or interviewers visiting in person, authentication information for surveys using the Internet, printed notices for surveys offering the possibility of replying by paper, etc.) or may be set out for each method (non-respondent, collection start/end date, reminder, etc.).

Conceptualise before implementation

Precisely defining the process to be implemented and following the GSBPM to break the process down into “phases”, which are coherent sets of area-specific actions, are prerequisites for any implementation in the various collection methods. Disconnected thinking would result in the creation of tools and processes that are inconsistent with each other or incompatible with the most demanding needs, such as online data collection and concurrent or competing interviewers, or even the monitoring of the consolidated process across different collection methods.

This does not preclude an incremental approach, both in the operations and in the complexity considered. Thus, within INSEE, the first developments concerned business surveys, which are more homogeneous than household surveys by nature.

Business surveys (first symphony)

INSEE’s Coltrane project has set up automated and shared services for business surveys, so as to allow collection either online or on paper. Coltrane faced a strong challenge to moderate costs, particularly in relation to specification, acceptance and IT development work. The platform and its associated services establish a process that, although adapted to business surveys, falls within a more global conceptual framework. In particular, a fine breakdown of the process, based on the GSBPM, allows for the separation of the respondent approach or access phases from the questioning phases themselves. Next, a “My Surveys” portal was created (Figure 1), which provides a “dashboard” for people responding within a company, who are interviewed multiple times and often in relation to multiple surveys at the same time.

In addition, a standardised mail offering and integrated automatic mail delivery processes are in place for all business surveys.

It is this fine breakdown of the process, particularly into survey access and questionnaire response phases, that will make reuse and sharing possible in the context of household surveys.

Online household surveys (a variation on the same theme)

While the initial operations concerned business surveys, INSEE has since extended the thought process and work to include household surveys.

To consider re-using the services implemented in a “business” context in a “household” context, even in “pieces”, it is the granular analysis of the collection process that makes it possible to propose scenarios. The services provided and the tools implemented, once correctly broken down, can then be “recomposed”. In the case at hand, it was necessary to make some changes in comparison with the Coltrane experiment.

Statistical questioning was first analysed as a common area need: it could therefore be implemented by the same technical departments, with calibration to provide suitable contextualisation for each type of respondent; this concerned:

- the first pages of the questionnaire (containing, in particular, the legal framework of the survey);

- the graphic charter of the questionnaire (e.g. the logo of the partner statistical services);

- the authentication mechanisms on the website (a different theme and instructions);

- support options for respondents.

In contrast, the needs of the two populations diverge significantly with regard to accessing the questionnaire. Indeed, business respondents are more familiar with Official Statistics surveys as they are often interviewed by several of them. In a “business” context, an access portal must therefore respond to the need for visibility across all surveys for which a respondent’s participation is requested; it must also take into account links between the contact person and the companies for which they are authorised to respond that are sometimes complex (for example, accountants are often respondents for several different companies for several different surveys). Thus, the decision was for a “My Surveys” portal, a site where a respondent can access the various questionnaires that apply to them, with reminders of deadlines. Functions to update personal contact details, which is particularly important information in a context where a single company is interviewed numerous times (at each round of certain surveys, or by different surveys), are also implemented.

Household needs are completely different: respondents are usually asked to respond to only one survey. They are not necessarily familiar with the concepts of Official Statistics surveys and they are often less inclined to devote time to them. In a “household” context, needs are more focused on information, or even on promoting the survey to the respondent. Thus, a so-called “Promotion” portal is proposed, displaying information about a particular household survey, its previous results, its legal framework and any other element that might encourage a response from the respondent household.

Sharing resources without dogmatism (a shared song sheet, risks of dissonance)

This “dissociated” approach is appealing in several ways. First, it offers an interesting modularity, with it being possible to re-implement or share each service, as desired. It also allows incremental implementation in which the area target is achieved in stages: no more monolithic “do it all” application, with its unavoidable redesign projects, but instead using product sets that evolve at different paces.

For example, this has made it possible to provide a multi-tenant portal for the Labour Force Survey, while retaining its traditional data collection applications: thus, the survey’s designers could carry out the methodological work needed to secure the switch to mixed-mode protocols, and could aim for a full “swing” only with new, mature tools. Furthermore, this is what makes it possible to ensure the collection of the online component of mixed-mode surveys, such as the Everyday Life and Health (VQS) survey or the Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) survey, providing follow-up and support in relation to this online data collection, while also retaining the traditional tools used by the interviewer component of the data collection.

The perfect conceptual target cannot be fully achieved, as the usual operational and budgetary constraints are very concrete realities. Thus, it is not just an ideal target, but a framework, a global coherence that the various operations must respect, good practices that must govern both the construction of the tools and the area practices.

For example, for mail and various communication media, the framework initiated with business surveys has been extended to include household surveys. Alternatively, the support services offered to respondents and their related processes ensure that the same criteria for security and confidentiality of personal information are respected. The same questionnaire design tools (Pogues and Eno) are used, which already incorporate good methodological practices.

However, pragmatism also means avoiding unnecessarily complicating an already unavoidably complex system. Excessive sharing or “genericisation” of resources must not become a dogma and the reuse of resources must be studied on a case-by-case basis.

The existence of the two types of portal for French Official Statistics surveys is a good illustration of this. It might seem appealing to imagine a “meta-portal” offering different contexts depending on the type of respondent. However, once correctly broken down into building blocks, only the authentication and assistance functions provided genuine opportunities for sharing resources. The two portals cover significantly different needs and are simple applications that benefit from remaining that way, in order to facilitate their maintenance and development. No significant structural gain can be expected (at present) from sharing resources. Once again, the metadata-based approach offers an interesting analytical angle; different natures of metadata, here the general information about a survey compared with company-contact links and multiple survey schedules, often suggest “distant” needs.

Poly-mode and mixed-mode, the same music?

The initial conceptualisation work for scaling up has enabled the collection process to be consolidated and re-established in several contexts: services from the “business” domain used in a household context and a collection process built around the concept of a survey unit, regardless of the collection method. It is possible to contextualise the different concepts, in accordance with the collection method.

However, can this process simply be used for an online collection method and for an interviewer-based collection method and then referred to as a mixed-mode collection? Has this issue of the mixed-mode data collection therefore been solved with this “poly-mode” vision?

It may be tempting to answer yes, but mixed-mode data collection cannot be reduced to merely several independent processes. This is because these processes need to interact (for example, the responses from one collection method must be able to be reversed in another) and sometimes even coexist (as in the case of competitive data collection between an interviewer and web). Being content with a poly-mode vision is not sufficient and the additional complexities inherent in mixed-mode data collection should be taken into consideration.

Furthermore, additional complexities also lead to additional concepts:

- mixed-mode questioning (re-use of responses from one method to another, consolidation of responses afterwards, etc.)

- a mixed-mode process (additional mixed-mode monitoring functions, quality control in a mixed-mode context);

- roles for the different stakeholders involved in a mixed-mode collection operation (use of interviewers for the resumption of incomplete online questionnaires, use of managers for the resumption of “in error” online questionnaires, etc.).

This, too, is a pre-analysis that is an essential step in any implementation of mixed-mode data collection. On this journey towards “genuine” mixed-mode data collection, it is necessary to start with the central issue when it comes to surveys: being able to use the data collected.

Each type of data has its own collection tool (the end of the one-man band)

The data collected is the main issue of the... collection process. The purpose of such a process is to collect these data and enable their use. This is primarily the data collected from a respondent through questions; however, there are other types of data:

- data allowing the monitoring and management of the collection operation (actions by interviewers/managers, paper envelopes returned due to an incorrect address and reminders sent);

- data on how the survey is being conducted: paradata, technical information collected on respondent behaviour (the different user clicks, the equipment used, the session duration, etc.).

The “traditional” channels of the INSEE surveys have not waited for conclusions on mixed-mode data collection to use and collect these different types of data: the strictly mono-mode approach often leads to the production of a questionnaire, a collection instrument, with the data model serving as an “all-in-one application” (collecting statistical responses, producing management and monitoring indicators, measuring technical times, classifying contact or non-response phases, etc.).

However, the processed data is not intended for the same stakeholders or the same uses. In addition, a dissociated approach calls for such data to not be collected by the same tools. Accordingly, within the new tools for the implementation of mixed-mode data collection:

- the data collected come from the collection instrument (the questionnaire);

- the monitoring/management data are the responsibility of the collection organisation tools (management position or interviewer collection position);

- in turn, the paradata are based on dedicated and specialised technical services.

Therefore, it is possible to offer a view of the data collected in one questionnaire or another (the retrieval of online data by an interviewer, for example) to allow simple viewing or modification of a questionnaire in a quality control context without interfering with the monitoring data of the interviewer activity, or to propose “warehousing of paradata”-type services to survey designers to support experimental approaches and methodological analyses.

The “omni-mode” questionnaire (multiple couplets, a single arrangement)

Once the different types of data have been collected, it becomes possible to deal with one of the major complexities of mixed-mode surveys: their statistical usability. “Collection method effects” – in which the answers to what is believed to be the same question vary according to the context of questioning – raise difficult questions in terms of using the statistics. In order to limit the effect, a certain number of principles are implemented not only within the mixed‑mode collection protocols, but also in the design of the survey questionnaire(s).

First of all, the questioning must be in mixed-mode format. In other words, it must be seen as a consolidation of different collection processes, which are operationally broken down according to the interaction methods implemented: the data collected must remain roughly the same, with adaptations being limited to operational or “ergonomic” considerations.

Discussions regarding the scope of mixed-mode questionnaires are not limited to the questioning alone; it is the actual variables collected and the “post-collection” processes that need to be consolidated.

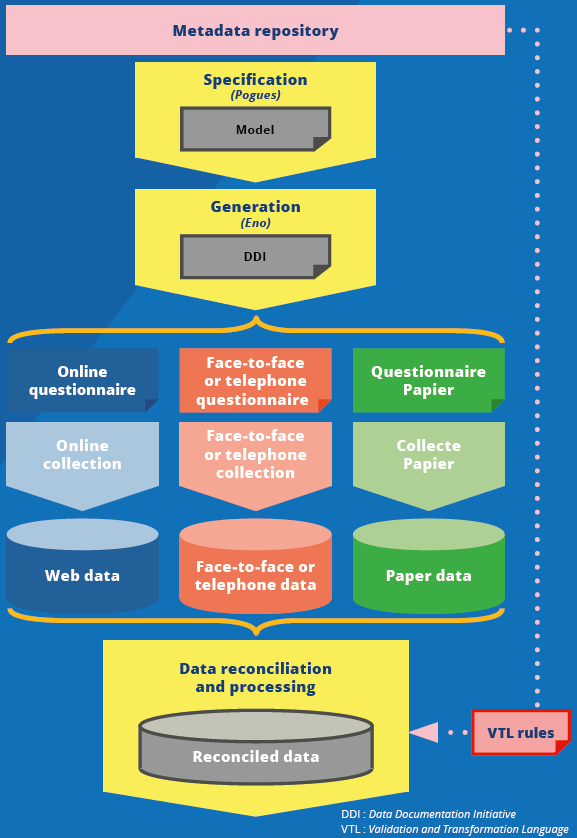

To ensure their usability, the data collected by different tools will need to use different technical channels before being finally made available in consolidated databases. There is also a need for a consolidated vision of the process to ensure consistency: use the same post-collection checks or even the same quality control tools. Such consolidation requires a major streamlining of the information system in order to ensure that the different collection methods “co-operate”.

The tools must allow the design of an omni-mode questionnaire, in that it is designed to ensure the most similar possible questioning across different collection methods, the most comparable values of collected variables and streamlined use.

The coverage of omni-mode questionnaires (in three octaves)

There are actually three dimensions behind the term omni-mode:

- the questionnaire is “unique” and common to all collection methods;

- the questionnaire is adapted to all collection methods;

- the responses from the different collection methods must be reconciled into a single statistical variable.

The first two dimensions are largely taken into account in the questionnaire design tools already used at INSEE: Pogues and Eno allow the same questionnaire objects (questions, response fields, etc.) to be automatically adapted to different collection methods and they limit the specific objects to a given collection method.

The breakdown of questionnaire objects into the different collection methods has already been mentioned; as for elements restricted to a single collection method, it is a practice that the tools allow but limit. The contextualisation of an instruction (for an interviewer or an online respondent, for example) is quite common and usual, but filtering questions or blocks of questions in accordance with the collection method must be managed so as to preserve the principle of the omni-mode questionnaire with the same variables collected. Good practice is to limit these cases to questions for which the answers can be imputed automatically, ensuring a certain degree of independence for the post-collection processing operations (each answer collected goes through the same processing chains, regardless of the collection method).

The theoretical example of the question “Are you personally able to access the Internet?” is a good illustration of this. In an online context, this seems superfluous and the answer could be imputed automatically as “Yes”. There are also questions about the description of a dwelling (for example, the distinction between an apartment or a detached house) that can be part of the interviewer’s preliminary identification phases and reduce the need for face-to-face statistical questioning (while remaining relevant in other collection methods).

The third dimension of the omni-mode questionnaire, that of consolidated statistical variables, is a developing area to examine. It would seem efficient to be able to specify not only the statistical variable, but also its collection method (the question, its wording, etc.) and the format constraints (the different controls in questionnaires) and to select the consolidation or automatic imputation rules to be applied to it post-collection.

Thus, returning to the previous illustrative example, an automatic rule to impute the answer “Yes” could be specified for online respondents alongside the wording of the question “Are you personally able to access the Internet?”. Furthermore, the specification of a single-value variable taken from a list of options (a “drop-down list” on the Internet) could be enriched by rules for mixed-mode consolidation and adjustment: consider the classic example of the exclusively “yes/no” answer for which a mischievous respondent can check both answer boxes on a paper questionnaire; when designing the question, an automatic adjustment rule could also be specified (uncheck the answer boxes or give preference to “Yes” if undesired multiple responses are provided).

This type of processing is currently carried out afterwards, as part of the post-collection processing, and it is done in a manner specific to each survey. An imputation rule of this type requires a certain degree of formality in how things are written and would enrich the questionnaire specification elements to describe these processing operations throughout the process. INSEE has started work based around VTL, a meta-language to specify algorithmic rules, promoted by Eurostat: the same language is used to specify the filters, the controls during or post-collection, the variables calculated within the questionnaire or the statistical variables to be delivered. In doing this, new metadata are “activated”.

Using an omni-mode conceptualisation of what statistical questioning should be, it is possible to limit the collection method effects, improve the statistical usability of the results and streamline the tools used in the consolidation of the collected variables. Thus, more than just questioning, it is a case of designing the collection of statistical variables, a “tree of variables” to be obtained, requiring the establishment of multiple collection processes, and all of the collected responses must be “reconciled” in a consolidated database (Figure 2).

Figure2. With omni-mode protocols, there are more rules for reconciling all data after mixed-mode collection

The challenges of the mixed-mode process (stakeholders who must act in concert with each other)

Mixed-mode collection, based on an omni-mode questionnaire, still poses a number of operational and organisational challenges.

What is the burden on an interviewer of a questionnaire collected via the Internet? A questionnaire taken from the Internet? How can an interviewer’s activities be coordinated correctly when there are mass paper reminders? How can complex events such as household, housing or budget breakdowns be reflected in the different processes? How can the work of interviewers be organised correctly when such events come from responses collected via the Internet?

The statistical quality obtained depends as much on the rigorous design of the questioning as on the implementation of the collection process in which each stakeholder has a role to play. With the advent of mixed-mode data collection, it is an entire process and the related roles and responsibilities of the different stakeholders that must be thought out. Once again, dissociating the methodological and statistical challenges facing a question designer (questions correctly understood, variables of interest identified, protocol managed) from the more operational challenges facing a collection process project manager (monitoring interviewers’ activity, managing the interviewer network, granular prioritisation of operations) is a preliminary step. Their objectives, while not diverging, benefit from being identified and consolidated respectively.

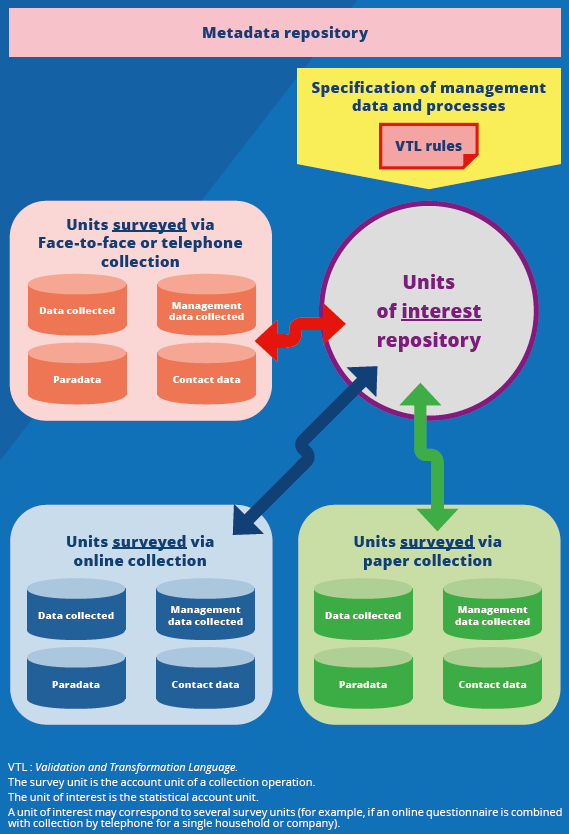

A new concept? The survey unit of interest (a new scope)

The project manager of a survey, who designs a survey, its protocol, its questionnaire, its schedule, etc. is interested first and foremost in the “initial” or “final” statistical unit.

This is the concept of the survey unit of interest that is introduced here: it corresponds to the statistical account unit resulting from the initial sampling. It ensures that the data related to this unit will be collected correctly (no duplicates, no “collection gaps”) and delivered correctly (a technical reconciliation in the form of statistical data before the correction of any collection method effects).

In turn, the statistical project manager must organise the work of the different stakeholders and implement the necessary tools, in order to allow the smooth running of the different, sometimes concurrent, collection processes across multiple surveys. He needs a collection unit, the survey unit, which will guarantee that the events, cost and charges associated with the process of collecting a unit will be recorded properly during the operations.

Without this dual concept, the “management control”-oriented information is mixed with more “statistical”-oriented information, and the objectives of each of these two approaches are corrupted.

A typical example is that of the traditional INSEE procedure in which “results codes” were produced. These aggregates were calculated during collection in order to provide both the elements for calculating interviewer performance as well as those necessary for adjustment, imputation and other statistical processing operations referred to as “downstream” processing. The list of existing “results codes” had become complex, difficult to maintain and difficult to consolidate across surveys and it was sometimes causing forced compromises regarding the statistical or operational need covered. The ambiguity over the term “out of scope” is a good illustration of this:

- it can be understood in the operational sense of the term (a destroyed dwelling, for example) and not be counted or included in the calculation of interviewer performance or in the statistical results;

- or it can be understood in an exclusively statistical sense (a household without a civil servant for a survey on the civil service as another example), but it must be counted as a successful survey by the interviewer.

To meet both needs, it is necessary to dissociate the concepts and, above all, to shift the calculation of the aggregates into the processes that consume them: one to compile a data warehouse useful for management control over the activities of the interviewers and the other to feed into the processing chains with qualification of the statistical response or, most often, non-response. As with the two portals adapted to the two types of survey respondents, this dissociation makes it possible to limit the complexity involved and to ensure that everyone’s needs are covered, with each party being responsible for their own aggregates.

At present, the tools that INSEE makes available to interviewers implement these principles. For example, the functions of organising and monitoring the collection are in application “building blocks” separate from the functions related to conducting a statistical survey.

Knowing how to and being able to make yourself heard across collection methods (to avoid the cacophony)

The last, but not least important, stage of conceptualisation, in order to be able to successfully implement mixed-mode data collection, concerns “mixed-mode communication”.

A mixed-mode process enables collection to be implemented regardless of the mode used. Consolidation at statistical questioning level guarantees statistical usability. Consolidation at statistical account unit level guarantees the coherent and efficient management of the successive collections of a survey. However, an additional dimension is not yet taken into account: the need for processes to communicate with each other “live”.

This communication is essential to enable competitive mixed-mode collection or mixed-mode collection based on reconciled sequences (for example, the processes for “online collection” and “interviewer collection” that need to be notified of each other), so as to allow consolidated monitoring of the various collection operations (the monitoring of the different survey units, regardless of the collection mode, must be consistent and consolidated in a single interface), or the implementation of hybrid data collection operations (such as those based on a diary survey, in which the start of the online collection of the diary must be synchronised with the visit of an interviewer).

In a “total” mixed-mode collection process, it is easy to imagine three to four simultaneous collection processes that need to communicate with each other. Do these different processes form a single complex, or are several “talking” to each other? How is it possible to ensure that this communication does not become a cacophony? In short, how should these parallel collection processes be designed?

The different collection methods in unison

At INSEE, this designing has been fairly “organic”. Starting from an initial conceptualisation of poly-mode collection, in which a collection process can be implemented several times in different collection methods, initial survey operations could be conducted. Thus, when the tricky question of ensuring that these processes communicate arose (for example, when an online collection operation must “warn” an interviewer that a response has been received, or when an interviewer must “warn” an online collection diary that a new respondent will arrive), the challenge was to maintain the stability of existing systems, as well as to ensure the continuation of the collection operations already implemented.

In a “mono-process” approach, a complex process with multiple collection instruments and multiple management and synchronisation rules makes it possible to manage all collection operations, from the most simple using only one collection method through to mixed-mode collection operations. Rather than opting for this approach, the choice was to use a “poly-process” approach, in which several processes coexist independently of each other and communicate with a central system (Figure 3). This system is therefore the conductor of the mixed-mode collection, the sole bearer of the complexity of the management rules related to the protocols (which collection methods should be used, which actions should be triggered, etc.).

Figure3. The management of mixed-mode collection generates a major need for synchronisation

Thus, the increased burden and the increasing complexity of the protocols under consideration

have limited impact on the complexity of each process. First, only the most complex

mixed-mode collection protocols require real inter-method communication (competitive

collection for employment figures or collection based on activity or budget diary,

in particular). The vast majority of collection operations, even mixed-mode ones,

are sequential and a “poly-process” model is perfect. Second, it is the central system,

responsible for the communication between each of the processes, which is most affected

by the level of complexity to be implemented. The developments to be made to the existing

systems to support the most complex protocols are thus limited (schematically, exchanges

of “messages” with a central system).

First mono-mode operations (with mixed-mode tones)

The first steps in scaling up, in accordance with the defined conceptual framework, aim to secure independent collection systems. A first collection via the Internet in a household context, a first collection by telephone and a first face-to-face collection.

While these first operations do not use mixed-mode “communication”, strictly speaking, the mixed-mode dimension is already present in the process and the work of the different stakeholders. For example, the first collection by telephone is taking place as part of a sequential mixed-mode operation, the 2022 pilot of the new Housing survey.

In sequential collection operations in which the first method is online, optimisation strategies are implemented for reminders and switching between collection methods. They require the stakeholders to have good command over the different processes and to be able to handle the different types of data (collected data, paradata and monitoring data) even if the tools do not formally communicate directly.

In these same collection operations, using answers provided earlier via the Internet in a collection operation by interviewers requires the specification of a methodological framework. Is the interviewer expected to resume the questionnaire completely, with the answers provided online serving as a “narrative arc” for a traditional interview? Or, on the contrary, is it an effective answer, with the answers provided online serving as a “stopgap” to allow a shorter interview? For the training of interviewers, the inclusion of this new area in their tasks is an integral part of the impact of mixed-mode data collection operations, from the first operations classed as “mono-mode”.

More generally, setting out and formalising mixed-mode protocols in instructions, tasks or roles of the stakeholders involved in the collection (from the interviewer to the survey project manager or the statistical project manager) is one of the challenges of these initial operations.

Improving virtuosity by tackling increasingly complex mixed-mode protocols

With the implementation of more complex mixed-mode collection protocols, it is no longer just the applications, tools or technical systems that need to evolve, but also the areas.

The method of analysing target processes in advance is still being used, with its set of questions:

- What is mixed-mode monitoring? What indicators can be used to monitor consolidated collection?

- What is the quality control for online household questionnaires? Should it be based on a “business” process, relying on managers? Or should the interviewer’s expertise be involved?

- How long does it take for an interviewer to resume an online questionnaire? More time, because there is advance preparation time and a support phase for the respondent that is slightly longer? Or less time, because the interview is shortened?

These are complex questions to which a priori answers cannot be accepted. Therefore, there will be further experimentation, to allow for testing and the determination of the facts. This means that the processes designed and the tools proposed will need to be sufficiently flexible: standardised services that are easy to implement and stakeholders who are trained and attuned to the experimental nature of the work. This is because, in a mixed-mode collection system, the complexity requires flexibility, in order for knowledge of this new area to be deepened and for interpreters of future collection operations to gradually take on the techniques of tomorrow.

Paru le :19/02/2024

At the very beginning of the 2000s, the Ministerial Statistical Office of the Ministry of Industry launched the first online surveys of Official Statistics. In their current guise, in 2021, 40 business surveys and 4 household surveys (including the Labour Force Survey) use online collection.

In respect of these issues, see the article by François Beck, Laura Castell, Stéphane Legleye and Amandine Schreiber on “Mixed-mode collection in household surveys: a modernised collection method and a more complicated process” also in this issue.

Editor’s note: musical metaphors will not surprise readers of previous issues on related subjects, such as (Cotton and Dubois, 2019; Haag and Husseini-Skalitz, 2019; Koumarianos and Sigaud, 2019).

The first work on the generation of questionnaires at INSEE dates back to 2013 and concerned the questionnaire of the annual sectoral survey of the business sector.

Generic Statistical Business Process Model, established within the framework of UNECE. See Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletUNECE (2019) and Erikson (2020) for an example of its operational implementation.

A collection instrument is the establishment of questioning in an operational context (online questionnaire, questionnaire adapted to a telephone call by an interviewer, adapted for an face-to-face visit by an interviewer or a paper questionnaire).

Formally, the GSBPM sets out 8 phases: specify needs, design, build, collect, process, analyse, disseminate and evaluate.

(Collecte Transversale d’Enquêtes – Transverse collection of data for business surveys) is now a complete service offering that allows survey designers: to collect responses online, to have a repository of contacts within companies and to manage it and to send letters, emails and paper questionnaires to companies that want them, while also having a dedicated support system (Haag and Husseini-Skalitz, 2019).

These shared mailing templates also conform to the recommendations of the Official Statistics Quality Label Committee.

With services specialised in publishing.

The sample drawing services offered by INSEE to its household surveys and to those of the Ministerial Statistical Offices (MSOs) ensure that an individual household is not re-interviewed from one survey to the next, so as to limit the burden borne by respondents individually.

The different types of mixed-mode data collection are detailed in the aforementioned article by François Beck, Laura Castell, Stéphane Legleye and Amandine Schreiber also in this issue.

In the case at hand, the Blaise data model.

For example, this avoids being obliged to become an interviewer when a person is a manager or being obliged to develop an ad hoc application.

Generic is an application for data retrieval by managers, relying on active metadata and automatic questionnaire generation. The implementation of paradata warehousing and of the process for the recovery of questionnaires from the web is also under way.

See the article by François Beck, Laura Castell, Stéphane Legleye and Amandine Schreiber also in this issue.

Beyond considerations regarding wording, this is seen as a textbook example of an “absurd” question in an online context.

This consolidated specification can then be automatically broken down into the different tools and processing operations, although using different computer technologies (Java, JavaScript, etc.). See (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSDMX, 2020; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBanca d’Italia, European Central Bank et INSEE, 2021).

Whether competitive or sequential mixed-mode collection is used, it remains a single account unit, with which multiple survey units may be associated, in different collection methods, at different times. It can be formally compared to the concept of the unit of statistical interest of the General Statistical Information Model (GSIM).

Pour en savoir plus

BANCA D’ITALIA, EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK and INSEE, 2021. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletVTL Community. Towards a community of VTL developers. [online]. GitHub. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

BONNANS, Dominique, 2019. RMéS: INSEE’s Statistical Metadata Repository. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 27 June 2019. Insee. N°N2, pp. 46-57. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

COTTON, Franck and DUBOIS, Thomas, 2019. Pogues, a Questionnaire Design Tool. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 19 December 2019. N°N3, pp. 17-28. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

COTTON, Franck, DUBOIS, Thomas, SIGAUD, Éric et WERQUIN, Benoît, 2021. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletA fully metadata-driven platform for the conception of survey questionnaires and the management of multimode data collection. [online]. 27-30 September 2021. Unece, Conférence des statisticiens européens, Expert Meeting on Statistical Data Collection. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

ERIKSON, Johan, 2020. Using a Process Model at Statistics Sweden - Implementation, Experiences and Lessons Learned. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 29 June 2020. Insee. N°N4, pp. 122-141. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

GUILLAUMAT-TAILLIET, François and TAVAN, Chloé, 2021. A new Labour Force Survey in 2021 - Between the European imperative and the desire for modernisation. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 8 July 2021. Insee. N°N6, pp. 7-27. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

HAAG, Olivier and HUSSEINI-SKALITZ, Anne, 2019. Internet Business Data Collection: INSEE Enters the Coltrane Era. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 19 December 2019. N°N3, pp. 45-60. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

KOUMARIANOS, Heïdi and SIGAUD, Éric, 2019. Eno, a Collection Instrument Generator. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 19 December 2019. N°N3, pp. 29-44. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

SDMX, 2020. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletValidation and Transformation Language (VTL). [online]. Uptated 4 August 2020. The official site for the SDMX community. A global initiative to improve Statistical Data and Metadata eXchange. [Accessed 6 December 2021].

UNECE, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGeneric Statistical Business Process Model GSBPM. [online]. January 2019. Version 5.1. [Accessed 6 December 2021].