Courrier des statistiques N6 - 2021

A new Labour Force Survey in 2021 Between the European imperative and the desire for modernisation

The new European regulation on social statistics (IESS), which has come into force in January 2021, requires greater harmonisation of the questionnaires of the European Labour Force Survey (LFS). The necessary overhaul of the questionnaire of the French LFS was an opportunity to adapt it to new forms of employment and emerging professional practices. In addition, by giving respondents the possibility of answering on the Internet during re-interviews, the French LFS has modernised its data mode collection. It is thus a pioneer in the direction taken by INSEE to develop multi-mode surveys, with the aim of maintaining high response rates over time and better targeting the work of interviewers.

In order to prepare for the transition to the new survey and to be able to meet the publication schedule, a large-scale pre-production operation, called Pilot, was conducted throughout 2020. The data collected, compared for one year with those of the LFS in production, make it possible to estimate the breaks that such a redesign is likely to induce on the main employment, unemployment and training indicators. By June 2021, INSEE will thus have been able to disseminate main labour market indicators from the new survey, and time-series corrected for the break.

- The source used to measure employment and unemployment, as defined by the ILO

- A key survey of the labour market statistics system

- A long history

- A survey that forms part of a European framework

- A continuous survey with a large sample size

- Why a new survey?

- A questionnaire that meets European requirements…

- … as well as national demands…

- Box 1. Some examples of new questions or questions responding to national needs

- … and is adapted to online collection

- The redesign of the questionnaire: a lengthy undertaking

- The general organisation of data collection remains unchanged

- A first interview still conducted face-to-face

- The choice of using the internet or telephone for re-interviews

- Box 2. The main lessons learned from the Muse tests

- To be able to manage a mixed-mode survey…

- … and reduce the burden on both respondents and interviewers

- Why have a major Pilot survey from 2020?

- A Pilot born from a set of constraints

- Estimating the break in the series and preparing for backcasting

- Legal references

Created in 1950 to provide a regular measurement of employment and unemployment, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) has undergone many changes over the years, regarding not only the information collected, but also methodological and technical aspects. The history of the LFS alone illustrates the significant developments in household surveys in recent decades. The entry into force of a new European regulation on social statistics, in 2021, invites us to turn to a new page in this story. The European obligation is an opportunity for a more profound reorganisation of the survey, which had not undergone any major changes since 2013. In particular, a new collection protocol now offers web-based response in a re-interview. What is unique about this redesign is that the entry into force of the new survey was preceded by a vast pre-production operation, called Pilot, which lasted throughout 2020 and the first quarter of 2021.

The source used to measure employment and unemployment, as defined by the ILO

Although its uses often go beyond this, because of its sample size and the richness of its questionnaire, the main objective of the Labour Force Survey is to measure employment and unemployment, according to the concepts defined by the International Labour Office (ILO) (ILO, 1982). These concepts are based on factual definitions of employment and unemployment, independent of the social regimes associated with the jobs or the support measures or benefit schemes for unemployment. They thus allow, insofar as possible, measurement that is stable over time and harmonised across countries. They are implemented by most of the world’s statistical institutes, especially those within the European Union. To improve comparability between countries, Eurostat proposes operational definitions of these concepts.

Many precise criteria are used to classify the population into employed, unemployed or inactive, as defined by the ILO. They concern, for example, whether or not people have worked during a given week, the reasons for absence for those who have a job but have not worked that week, whether people have taken specific steps to look for a job or whether they are available for work. No administrative register contains such information; it can only be collected through questions in a household survey. In France, that survey is the Labour Force Survey.

A key survey of the labour market statistics system

There are many advantages to the Labour Force Survey, which give it a key place within the labour market statistics system. The richness of its questionnaire (Figure 1) allows it to shed light on many aspects of the relationship to employment, well beyond the mere measurement of employment or unemployment; the concepts of under-employment and the unemployment halo, for example, make it possible to reveal the porosity of the boundaries between employment, unemployment and inactivity; a detailed description of the jobs (contract, working hours, occupation, status, etc.) makes it possible to state the quality of the jobs.

Conducted for decades, the Labour Force Survey can identify long-term changes in the labour market. Its inclusion in a European framework makes it a valuable tool for international comparisons.

The Labour Force Survey is used in a variety of ways, both in France (INSEE, Ministerial Statistical Offices and other French institutions such as the Treasury and France Stratégie) and abroad (Eurostat, OECD, etc.). In addition to the quarterly publication of a set of indicators shedding light on labour market conditions, including its flagship indicator, the unemployment rate, the survey is used for more structural or evaluative studies on various subjects, for example on long-term unemployment, the unemployment halo or short-term contracts.

Figure 1. A Questionnaire that Covers a Lot of Topics

A long history

Since its inception in 1950, the French Labour Force Survey has undergone many changes, both conceptual, to conform to ILO or Eurostat guidelines or to better measure labour market changes, and in terms of statistical engineering (sampling methods or treatment of non-response, collection modes, etc.) or technical aspects, with the increasing computerisation of data collection and processing (Goux, 2003).

Without going into detail about its entire history, the last twenty years illustrate the significance and variety of the changes that the survey has undergone. The year 2003 is a first milestone: following a European decision, the annual Labour Force Survey becomes a “continuous” survey, meaning that it has since covered all weeks of the year. It is therefore a major source for the analysis of market conditions. Another important date is 2009: in response to a “controversy” over unemployment figures in 2006-2007 (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDurieux et al., 2007), its sample is increased by 50%. In 2013, its questionnaire is changed to make it easier to administer, particularly over the telephone, to improve the coding of occupation and diploma variables, to enrich knowledge of the labour market and to comply with Eurostat guidelines on some indicators (training and unemployment halo). The measurement of employment and unemployment will be affected by this. In 2013, the computer application for managing the survey, which is a vital tool for a survey of this scale that is subject to strong production constraints, is also overhauled. In 2014, the geographical scope of the survey was extended: French overseas departments (excluding Mayotte) are included in the continuous Labour Force Survey process.

Each change to the survey affecting the measurement of the indicators entails a major correction for breaks in time series exercise, i.e. the production of break-corrected series to provide a consistent view of the labour market. For this reason, the Labour Force Survey does not change every year, but every ten years or so, as part of heavy redesign exercises.

A survey that forms part of a European framework

Since 1973, the Labour Force Surveys has been part of a European regulatory framework, which has evolved towards increasing harmonisation. This framework sets out some constraints, but also allows countries a degree of freedom in the implementation of the survey. Thus, whether it is the regulation that prevailed until 2020 (Regulation 577/1998 of 9 March 1998) or the one that has been in force since (IESS FR – Integrated European Social Statistics Framework Regulation), the information that the survey must collect is defined at European level, which constrains the questionnaire to some extent.

Similarly, the European regulation imposes some methodological principles, whether relating to the sample (such as having a rotating sample, having a sample evenly distributed over the whole year and of sufficient size, via requirements in terms of the accuracy of the indicators), or to downstream processing (by imposing, for example, that the survey be calibrated to population margins at regional level).

Finally, by limiting the maximum collection period to five weeks, for example, the Regulation provides a framework for some aspects of the protocol.

The European constraints are minimum requirements. In the case of France, we often go beyond this, for example in relation to the data collection period, for which we impose a smaller window, or to the questionnaire, the French edition of which contains many questions that are not required.

In contrast, other aspects of the survey are left to the discretion of the countries. This is applicable to using a sample of individuals or dwellings or to the collection mode; countries are thus free to use collection modes that either involve an interviewer (by telephone or face-to-face) or do not (by internet or on paper) (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEurostat, 2019).

A continuous survey with a large sample size

A key characteristic of the French Labour Force Survey, which determines its sampling and strongly impacts the way in which its collection is organised, is the fact that it is a continuous survey: the sample is divided over all the weeks of the year; it is as if the survey were carried out on 52 independent samples. Each weekly sample is associated with a so-called reference week, in relation to which respondents are asked to describe their employment situation.

To avoid recall bias and ensure quality data, the collection period is very short: until 2020, respondents had to respond within two weeks and two days after the reference week.

Another feature of the survey is that it concerns a panel of dwellings. Inhabitants of the sampled dwellings are interviewed six quarters in a row, in order to estimate trends more robustly and to produce longitudinal analyses. Until 2020, for the first and last interviews, households were interviewed face-to-face; for the intermediate re-interviews, for which the questionnaire was shorter, they were interviewed by telephone. The questionnaire consists of a part that briefly describes all the inhabitants of the dwelling, followed by an individual questionnaire to be answered by each inhabitant of the dwelling aged 15 or over. The questionnaire includes each year an ad hoc module, a set of twenty or so questions which shed light on a particular theme.

The Labour Force Survey is a large-scale operation. Each quarter, almost 100,000 people respond to the survey. In 2019, it alone accounted for more than one third of the survey burden placed on the INSEE households.

Why a new survey?

Since 2014, the Labour Force Survey had not seen any major changes, but in early 2021, a new Labour Force Survey was introduced, primarily to meet a European requirement. Indeed, the new Integrated European Social Statistics (IESS) Framework Regulation has been applicable to statistical institutes since the beginning of 2021 (Cases, 2019). It does not significantly change the European requirements in terms of statistical engineering or protocol; in particular, it still leaves countries free to choose their collection mode. Its main ambition is to further harmonise the information collected, both between countries and between the different surveys it covers. The innovation introduced by the IESS Framework Regulation is, in fact, providing a single framework regulation for all the European social surveys.

The new regulation also reaffirms the need to cover the whole national territory, which is not yet the case as the department of Mayotte is still covered by an annual survey (see above). Mayotte will join the LFS in force in the rest of the national territory in 2024, while this project is being studied and the appropriate organisation is being put in place.

In order to introduce a single break in time-series, the redesign made necessary by these new European requirements provided an opportunity to incorporate other developments desired at national level, but not required at European level. The first of these was to modernise the survey’s collection protocol by proposing the internet as an additional response mode, in line with INSEE’s policy of developing multi-mode surveys, following the example of many other national statistical institutes. The second involved the update of the weighting method used for the survey.

A questionnaire that meets European requirements…

The overhaul of the questionnaire serves three purposes. Firstly, and this was unavoidable, it had to be brought into line with the IESS Regulation, which updated the list of information required. For example, reasons for migration, contractual working hours or having worked during studies are now included in the required variables. However, insofar as the French questionnaire was already much richer than required by Eurostat, few new questions had to be introduced.

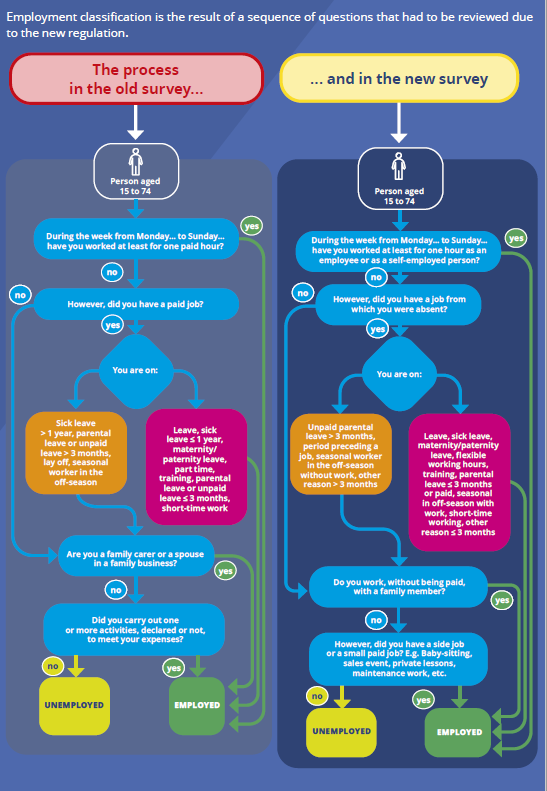

However, Europe has taken the ambition of harmonisation between countries a step further: for the most central variables, i.e. those used to determine activity status as defined by the ILO, the order of the questions and the flow of the questionnaire are now mandatory. This is the major innovation introduced by the IESS Framework Regulation. It did not result in a major change to the French questionnaire: this was already quite close to the new European framework, even if on closer inspection there are more changes than it would appear. For example, Eurostat’s new interpretation of the ILO criteria leads to the classification of persons who report having a job but being absent from work due to illness for any length of time as employed, compared to a limit of one year in the old survey. Similarly, people absent from work for parental leave are now classified as employed if their absence is less than 3 months as well as, and this is new, if they perceive a job-related income, such as the shared child-rearing benefit in France (Figure 2). As another example, the position of the questions on the desire to work and on job seeking is reversed, returning to the situation that prevailed before 2013. Finally, the list of job seeking approaches is much shorter than in the previous survey. These are merely examples. All of these changes are likely to affect the measurement of employment and unemployment by the survey.

Figure 2. From Conception to Implementation in the Questionnaire, the Example of Employment

… as well as national demands…

In addition to the European requirements, the redesign of the questionnaire was an opportunity to respond to national expectations on subjects that had, at that time, not been covered or covered little by the Labour Force Survey. There are primarily questions relating to:

- working conditions including, in particular, questions on teleworking (only working from home, which is European information, has been covered by the survey so far);

- new forms of employment (e.g. to identify temporary workers with permanent contracts, apprentices on permanent contracts, or the dependent self-employed workers), in line with the recommendations of the National Council for Statistical Information (CNIS) (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGazier, Minni and Picart, 2016);

- and job-related non-formal training.

The new questionnaire also incorporates new questions in order to implement the new ILO nomenclature on employment status, which was defined at the 20th International Conference of Labour Statisticians in October 2018 (ILO, 2018). On this point, France is ahead of the European agenda: Eurostat has only just launched, in early 2021, a task force to investigate the implementation of this new nomenclature in the Labour Force Survey.

The new French Labour Force Survey is also the first household survey to implement the updated national nomenclature of occupations (professions et catégories socioprofessionnelles – PCS) (Amossé, 2020).

Finally, certain specific French features were reaffirmed at the time of this redesign (Box 1); in particular, these include the collection of information on the parents’ occupation and questions on the receipt of social benefits.

Box 1. Some examples of new questions or questions responding to national needs

Franco-French questions that existed and are retained

- Occupancy status of the dwelling, receipt of housing benefits (dwelling questionnaire)

- Characteristics of job sought or desired (contract, working hours) (modules A and B)

- Situation on joining the company, situation before starting the job, assisted contracts (module B)

- Date of completion of initial studies (module D)

- Pensions and other benefits (module F)

- Profession of father and mother (module H)

New European questions

- Contractual hours (module B)

- Employment experiences during the course leading to the highest qualification (module D)

- Previous country of residence, reason for migration (module H)

New Franco-French questions

- Questions for coding the PCS 2020, module on clients and other relationships of the self-employed, remote working, profession and contract in secondary employment (module B)

- Last employment contract (module C)

- Description of most recent non-formal training for professional purposes (module E)

… and is adapted to online collection

The design of the new questionnaire had to take into account the other major innovation brought about by the redesign: the introduction of self-administered online questionnaire for the re-interviews. Given that the objective was to have a single questionnaire, regardless of the collection mode, it was necessary to find simple formulations that were adapted to self-administration.

The most emblematic development in this respect concerns the collection of occupation and diploma. The previous protocol was to enter these labels in plain text. It required a great deal of training and support for interviewers and was clearly not suitable for self-administered data collection. Accordingly, the selection from a pre-defined list was introduced. In view of the large number of occupations (the list contains no fewer than 5,000 labels), the challenge was to develop effective tools for navigating the list, closely following the protocol established by the CNIS working group dedicated to the redesign of the PCS (Amossé, 2020).

Furthermore, the online collection for the re-interviews required a fluid and short questionnaire, while ensuring that changes in situation were well identified. In particular, it was necessary to greatly reduce the size of the questionnaire of the last interview (see collection protocol below), previously conducted face-to-face. To achieve this, questions were moved from the last interview to the first one. This was the case for the ad hoc module, in particular. To compensate, the module on the situation one year earlier, which was asked in the first interview, has been removed; it was found to be subject to memory bias and was losing relevance with the development of longitudinal uses of the survey.

Finally, the processes for the transition to the new survey were determined: a switch on a given date for all surveyed units, regardless when they entered the panel. It was therefore necessary to design a specific questionnaire, known as a switchover questionnaire, to manage this transition. The switchover questionnaire is a hybrid questionnaire that mixes first interview and re-interview questionnaires.

The redesign of the questionnaire: a lengthy undertaking

The work to design the new questionnaire was carried out within the European framework and took place over a period of around ten years. To draw up the new texts governing the Labour Force Survey, Eurostat set up several working groups (or task forces) dedicated to certain parts of the questionnaire. In spring 2011, a task force was assigned to draw up a new operational definition of employment and unemployment based on the principles of the ILO, which have remained unchanged; another was dedicated to measuring working time (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEurostat, 2018) and a final group was set the objective of redefining the content of all the ad hoc modules.

Once the European framework was sufficiently defined, the design work could be launched at French level. In 2017-2018, no fewer than ten working groups covering all the themes of the survey brought together experts from throughout the Official Statistics.

The new questionnaire has been tested on several occasions: in June 2018, the first interview questionnaire was tested face-to-face with 1,000 households; in December 2018, a 100% online test was carried out with volunteers; in 2019, a full test, in two waves (first interview and re-interview), was carried out with 1,400 households according to the protocol that was intended to be used for the target audience.

The general organisation of data collection remains unchanged

The protocol for the new survey was developed by an internal INSEE working group, which involved survey managers and interviewers.

The general organisation of data collection remains unchanged: the data collection remains organised continuously over all the weeks of the year and structured around the reference week; the surveyed unit remains the dwelling, which is surveyed in six consecutive quarters. Response by a third party (proxy), in case of the concerned person is absent, is still allowed.

The protocol for the Labour Force Survey differs greatly, depending on whether the household is being interviewed for the first time or being re-interviewed. With the redesign, the protocol for the first interview has changed little, while the protocol for re-interviewing has changed more.

A first interview still conducted face-to-face

The protocol for the first interview retains the two main characteristics that it had until late 2020: a field trip and a face-to-face interview.

The sample of the Labour Force Survey includes vacant dwellings and secondary residences, as the status of the dwelling may vary between the sampling frame and the collection. It is therefore important for the interviewer to check, by means of a field trip, that the dwelling still exists, that it is occupied and used as a private household. During the reference week, the interviewer carries out this identification phase and makes contact with the persons to be interviewed. New information has been added to assist the interviewer: the telephone number and e-mail address of the occupants of the dwelling are now provided when they are available in the sampling frame.

The first interview of a household is still conducted by a face-to-face interview. This is the case for dwellings entering the sample, as well as for new households during the panel, either because the dwelling was previously vacant, or because the household did not respond to the survey, or because there was a change of household due to a move. In the first interview, concepts can be clarified by the interviewer and the questionnaire is longer. This contact with the interviewer is also important for establishing trust with the household and a commitment for the duration of the panel.

Retaining a first face-to-face interview is a divisive point between countries: some countries have made the same choice as France, such as Germany, Portugal or Belgium; others have preferred to introduce the internet from the first interview, under severe cost constraints and after having substantially reduced the size of the questionnaire; this is the case in the Netherlands and Denmark, for example.

In France, the main change in the protocol for the first interview is the extension of the collection period to three weeks. Interviewers are still instructed to carry out as many interviews as possible at the beginning of the period; firstly, to limit memory bias (most of the questions relate to a very specific period, the reference week), and secondly, because the interviewer thus gives himself or herself the means of interviewing the people who are least available.

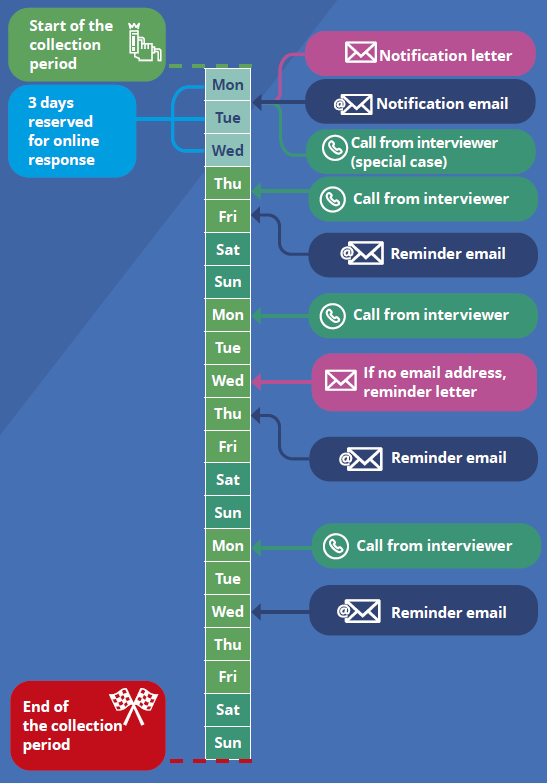

The choice of using the internet or telephone for re-interviews

In the re-interviews, in contrast, whether in the intermediate re-interview or the final re-interview, the protocol changes significantly. The internet is introduced as an alternative response mode to the telephone. The challenge was to develop a good connection between the two modes so that, within the three-week collection period, the addition of one mode would result in at least maintaining the response rate. Although the broad outlines were defined, several experiments were necessary to refine all the parameters of the protocol: the duration of internet exclusivity, the media (mail or email) to be used to communicate with households, dates of reminders, etc. (Box 2).

More specifically, on the Monday of the first week of data collection, all respondents receive a notification letter and a notification email with the address of the collection website and their login details, inviting them to complete the questionnaire online.

In general, the first three days of collection are reserved for online responses (Figure 3), so as to relieve the interviewers of the responses provided without difficulty and without delay by respondents (Garnero, 2019). It is only from the Thursday of the first week of collection that the interviewer can call the household if it has not already answered and offer to fill the questionnaire by telephone. Interviewers call until the questionnaire is completed. The collection website remains accessible to the household until it has completed the survey, regardless of the completion mode, and at the latest until the Sunday of the third collection week. Households for which a valid email address is available received up to three reminders by emails; the others receive a remind letter.

In some cases, the telephone survey may start from the Monday of the first week of collection. These cases are respondents identified as unlikely to respond online or cases in which interviewers know in advance that they will be absent, which makes it possible to spread their workload. As before, in rare cases left to the discretion of the interviewer, the survey may be conducted face-to-face, for example for large households or those with poor French language skills.

Box 2. The main lessons learned from the Muse tests

The Mixed-Mode Labour Force Survey (Multimode sur l’enquête Emploi – Muse) project sought to trial the use of the internet in the collection of the Labour Force Survey (Garnero, 2019). In total, seven trials were carried out between 2014 and 2018:

- to develop a “fluid” questionnaire for the online version (2014-2015);

- to test the operation on a large scale on INSEE’s servers, with a sample of 30,000 households interviewed three times exclusively online (2016);

- and to test several variants of a mixed-mode internet/telephone protocol (2017-2018).

The tests confirmed that the first interview should remain a face-to-face interview:

- because it is preferable for the different concepts to be introduced by an interviewer;

- because the time needed to complete the questionnaire is not suitable for an online response.

In contrast, the response time required for an individual questionnaire is much shorter in the re-interviews. It takes twice as long online as it does over the telephone, but it is not necessarily perceived this way by respondents.

As with the census, the households most likely to respond online are younger, more affluent and more “connected”, in the sense that they have more often provided an email address to the tax authorities.

Online, respondents complete their own individual questionnaire more often than by telephone or in face-to-face interviews. It is as though the household members passed on the link on the questionnaire to each other, whereas on the telephone it is common for one person to answer for all or some of the household members.

In the 2016 large-scale trial (in which response was mandatory), the response rate in the first interview was 31%; 57% responded in the second interview and, of the latter, 78% responded in the third interview. In the (non-mandatory) mixed-mode online/telephone test, the response rate of clusters for which the test could be carried out without major IT incidents was 35% for online and 26% for telephone.

Online responses are quite concentrated at the beginning of the collection period.

Notification letters are more effective than notification emails. However, the impact of a paper reminder differs little from that of an email reminder.

The mixed-mode online/telephone survey process was well received by interviewers during these tests, as they appreciated the reduction in the burden of telephone re-interviews, which was perceived to be excessively repetitive. The initial period reserved for online responses lightens the burden on interviewers and allows them to better target their intervention.

The three-week period is considered sufficient to switch from one collection mode to the other. Telephone reminders to encourage households to respond online do not seem appropriate: when the interviewer contacts a person by telephone, the most effective way is to offer to carry out the survey immediately by telephone.

Figure 3. Three Weeks of Re-Interviewing to Respond Online or by Telephone

To be able to manage a mixed-mode survey…

For mixed-mode survey management to work smoothly, interviewers must be fully informed of what they must do and of the progress of the collection. To that end, they have a “tour book” on their computer, which shows all of the dwellings assigned to them, as well as the date they are supposed to intervene (Monday or Thursday) and the completion of the questionnaire online.

When contacting the household, the interviewer is thus in a position to know whether to encourage to finish the questionnaire if good progress has been made online, or whether it is preferable to complete the questionnaire by telephone.

Respondents who experience difficulties with the survey (connection problems, difficulties in answering a question, etc.) or wonder about its objectives, duration, future re-interviews, etc. can contact a help-desk, by email or telephone. A common difficulty faced by households is forgetting or losing their password. In this case, respondents who have provided an email address can immediately obtain a new password from the survey website without even contacting the help desk; for others, they have to follow an authentication procedure.

… and reduce the burden on both respondents and interviewers

This mixed-mode survey protocol aims to encourage households to respond, as they are increasingly keen to use the internet for their daily activities or to respond to surveys. It is also intended to lighten the burden on interviewers, for whom telephone interviews are repetitive. However, even in re-interview, the role of the interviewers remains crucial in obtaining responses from households that are less familiar with the internet or more sensitive to telephone reminders.

As the survey is a relatively burdensome panel (six interviews separated by only one quarter), an important issue is to keep the survey burden on households to a minimum. This requires work on the questionnaire, as mentioned above, but also a variety of possible response modes, adapted to the wishes of households.

Some populations feel less involved by the survey and would be difficult to retain over the duration of the panel even though their situation does not change. These are generally older people and disabled people. Eurostat has proposed simplified rules for these people: from the first interview, people aged 90 or more are removed from the scope of the survey; inactive people aged 70 or more, as well as inactive disabled people, are not re-interviewed and their responses from the first interview are “copied”.

Finally, in order to reduce the burden on interviewers, secondary residences and non-ordinary dwellings, which are unlikely to change in use over the duration of the panel, are removed from the sample once their status has been confirmed in the field. In contrast, the dwellings identified as vacant are scheduled for collection every quarter as a not insignificant proportion of them are likely to become main residences over the duration of the panel.

Why have a major Pilot survey from 2020?

The experience of the previous redesign of the Labour Force Survey in 2013, when a simple “tidying up” of the questionnaire was not expected to have a significant impact on the indicators, has left its mark. It was indeed a complete surprise when the first uses of the new questionnaire revealed breaks in the indicators. After many checks, once the correct functioning of the entire production chain had been confirmed, the evidence had to be accepted: the changes made, particularly concerning the order of the questions on the desire to work and job-seeking, had caused a break in the series for unemployment rates. The 2021 redesign, which was to fundamentally overhaul the questionnaire, change the protocol and update the weighting method, was also likely to cause a break in the main labour market indicators. It was therefore necessary to carry out a preparatory operation, aimed at ensuring the correct functioning of the tools (management application, IT architecture adapted to a mixed-mode survey), to prepare the processing chain downstream and to provide sufficiently precise information to best estimate breaks in the series and to be able to produce break-free time-series.

Aware of the need to inform users of changes affecting these indicators, most notably the unemployment rate, Eurostat has strongly urged Member States to put in place ambitious operations to estimate the break caused by implementation of the new regulation in order to provide break-free series. The European guidelines were thus in line with the objectives that INSEE had set for this new redesign.

A Pilot born from a set of constraints

In 2017-2018, INSEE began designing this preparatory operation, which had to take into account a whole range of constraints.

The first of these was the scale of the planned redesign, which affected several aspects of the survey: it was not possible, as in 2013, to carry out an analytical deconstruction of the questionnaire; a complete survey had to be conducted.

The second constraint concerned the timetable: the date of entry into force of the new regulation, 2021, the fact that INSEE planned to keep the timetable of its quarterly dissemination unchanged and the fact that the experience of 2013 had shown that the impacts could vary over the year, due to seasonal behaviour, particularly during the summer. It was therefore decided to carry out the preparatory operation in 2020 and to cover all the quarters. This meant that a very tight preparation schedule was necessary, especially as important parameters depended on European decisions that were still pending at the time.

The third constraint, which had to determine the size of the operation, had to reconcile two contradictory requirements: a precision requirement, in order to be able to detect significant impacts, and a cost limitation requirement. It was therefore decided to draw a quarter of the sample for the survey in production to carry out the Pilot.

Finally, the Pilot was intended to ensure that all the mechanics of the new survey were working and to estimate the breaks in the series introduced by the new survey. It therefore had to play out in advance exactly what was going to happen when the new survey came into force and be fully consistent with what the new survey would be like, in terms of questionnaire, protocol or even downstream processing method.

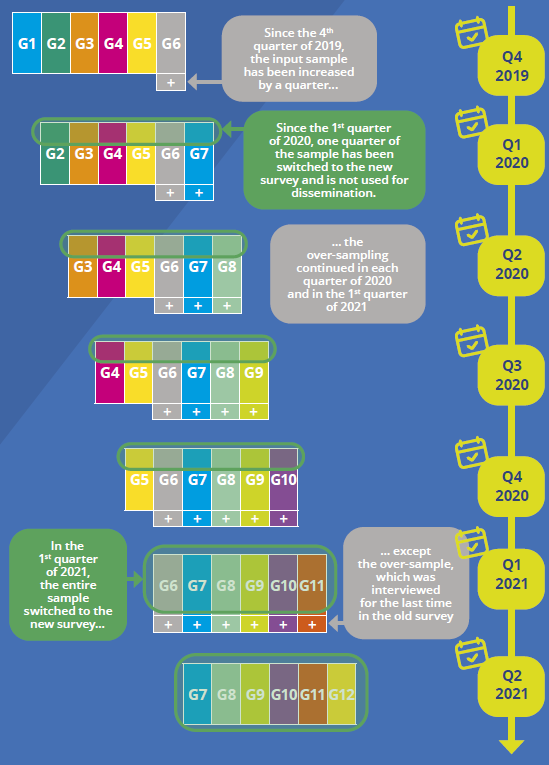

Ultimately, the Pilot consists of two components (Figure 4):

Figure 4. The Pilot, an Early Switchover and an Over-Sample Throughout 2020

- an early switch to the new survey: one quarter of the sample, across all waves, switched to a new survey as of the 1st quarter of 2020. This switch presaged the one that took place in the 1st quarter of 2021 for the rest of the sample;

- an over-sample in the old survey: an additional sample, introduced gradually from the 4th quarter of 2019, was re-interviewed in the old survey until the 1st quarter of 2021 inclusive. Thus there was a complete control sample (waves 1 to 6) in the old survey as at the 1st quarter of 2021, when the new survey entered into production. This over-sample was also used for dissemination in 2020, partly offsetting the drawing carried out for the “switchover” component.

In the 1st quarter of 2021, the first part that had switched one year earlier was completed by the remaining three quarters that had remained on the old survey and have now switched in turn. The survey sample thus regained its “full” size.

Estimating the break in the series and preparing for backcasting

The primary objective of the Pilot was to provide a set of information so as to allow the potential breaks in the series caused by the new survey to be estimated as accurately as possible. The major difficulty in estimating breaks in the series was the large margin of uncertainty surrounding the estimates: in the old survey, despite the large sample size, the quarterly unemployment rate is estimated with an accuracy of ± 0.3 percentage points. With the Pilot system, by comparing the indicators measured through the old survey and through the new survey, five quarterly measurements were available for breaks in the series, from the 1st quarter of 2020 to the 1st quarter of 2021. The availability of multiple quarters made it possible to measure the break in the series as an annual average, with greater precision, as well as to detect possible seasonality in the impacts. However, in view of the large margin of uncertainty expected for the estimates, only significant seasonal changes could be identified. Finally, the 2020 sanitary crisis has made the measurement of breaks in the series more complicated, as it can have different impacts on both surveys, the old one and the new one.

Due to the multiplicity of sources of serial for breaks in the series and potential cross-effects, the preference was to estimate the break in the series in an overall manner, by comparing the two versions of the survey, without seeking to systematically quantify the specific contribution made by each change. Nevertheless, it was possible to isolate some specific effects, e.g. with regard to conceptual changes or changes in the weighting method (INSEE, 2021). Isolating the effects of the change in questionnaire or the effects of responding using the online response mode (Vinceneux, 2018), which combine a “measurement” effect (the fact that a person responds differently online than to an interviewer) and a “selection” effect (the fact that responding online allows new respondents to be included), is more complex and could be the subject of future analysis.

The aim was to obtain an estimate of breaks in the series in order to produce break-free series for the main indicators as soon as the results for the 1st quarter of 2021 were published, so as to be able to communicate on developments between the 4th quarter of 2020 and the 1st quarter of 2021 that make sense.

Legal references

Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletRèglement 577/98 du Conseil du 9 mars 1998 relatif à l’organisation d’une enquête par sondage sur les forces de travail dans la Communauté. In: Office des publications de l’Union européenne. [online]. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletRèglement 2019/1700 du Parlement européen et du Conseil du 10 octobre 2019 établissant un cadre commun pour des statistiques européennes relatives aux personnes et aux ménages fondées sur des données au niveau individuel collectées à partir d’échantillons. In: site EUR-Lex. [online]. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletRèglement d’exécution 2019/2240 de la Commission du 16 décembre 2019 spécifiant les éléments techniques de l’ensemble de données, établissant les formats techniques de transmission des informations et spécifiant les modalités et le contenu détaillés des rapports de qualité concernant l’organisation d’une enquête par sondage dans le domaine de la main-d’œuvre conformément au règlement (UE) 2019/1700 du Parlement européen et du Conseil. In: site EUR-Lex. [online]. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

Paru le :02/10/2023

This is the IESS Framework Regulation, see below and also the references to regulations at the end of the article.

At that time, the level and development of unemployment was monitored using two sources: administrative data on jobseekers and data from the Labour Force Survey. The results of the two sources were linked by calibrating the administrative data to the unemployment measured by the Labour Force Survey. In 2006, for the first time in 20 years, this calibration could not be carried out due to a strong divergence between the two sources. Subsequently, this calibration was discontinued and measures were taken to improve the accuracy of the Labour Force Survey and the understanding of the differences between the two sources.

An annual survey has been conducted in Mayotte since 2013.

The new European regulation also imposes precision levels to be reached for some key indicators, such as the unemployment share for the Labour Force Survey, leading to constraints in the sample size and its regional allocation. For the Labour Force Survey, these constraints have been taken into account in the renewal of its sample, since the 3rd quarter of 2019, as part of the renewal of the INSEE master sample (Sillard et al., 2020).

In particular, the Netherlands and Denmark have been pioneers in responding to the LFS online. See also (Signore, 2019).

These modules are now fully integrated into the Labour Force Survey. An eight-year cycle was defined, with six recurring themes: accidents at work and occupational health problems, the labour market situation for immigrants and their descendants, retirement and labour market participation, young people in the labour market, achieving a work-life balance, work organisation and working time arrangements.

Due to the health crisis, since March 2020, face-to-face interviews have been suspended several times and temporarily replaced by telephone interviews. In certain periods when restrictions on movement were most severe, identification operations could not be carried out.

The online household survey portal can be accessed via the INSEE website. The Labour Force Survey is available at: Ouvrir dans un nouvel onglethttps://particuliers.stat-publique.fr/eec.

Tests carried out as part of the Muse project showed that more than 10% of respondents responded within the first few days, and that the first email reminder was most effective when sent at the end of the week. The timing of the reminders supports the online response throughout the three weeks of collection.

These households responded by telephone to the previous question, did not provide an email address, and answered “no” to the question “Would you have had the equipment and knowledge to respond online?”. They still receive login details in the notification letter.

It is currently not possible to finish a questionnaire started online by telephone.

In France, conditions regarding age or previous activity have been added.

Due to the rotating nature of the sample and its size, the transition from the old survey to the new one was done in the form of a switchover (and not a gradual ramp-up), as was done in 2013.

Pour en savoir plus

AMOSSÉ, Thomas, 2020. La nomenclature socioprofessionnelle 2020 : Continuité et innovation, pour des usages renforcés. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 29 June 2020. INSEE. N° N4, pp. 62-80. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

CASES, Chantal, 2019. IESS : l’Europe harmonise ses statistiques sociales pour mieux éclairer les politiques. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 19 December 2019. INSEE. N° N3, pp. 125-139. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

DURIEUX, Bruno, DE NANTEUIL, Yann, RÉMOND, Sébastien, DU MESNIL DU BUISSON, Marie-Ange, GRIVEL, Nicolas et WANECQ, Thomas, 2007. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletRapport sur les méthodes statistiques d’estimation du chômage. [online]. 1st September 2007. Inspection générale des Finances, Inspection générale des Affaires sociales. N° 2007-M-066-01 and RM 2007-141. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

EUROSTAT, 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletQuality issues regarding the measurement of working time with the Labour Force Survey (LFS). [online]. 13 March 2018. Statistical reports. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

EUROSTAT, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLabour Force Survey in the EU, candidate and EFTA countries – Main characteristics of national surveys 2018. [online]. 15 November 2019. Statistical reports. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

GARNERO, Marguerite, 2019. Le projet Muse : 5 ans d’expérimentations pour préparer l’introduction d’Internet dans l’enquête Emploi. [online]. 11 December 2019. INSEE. Documents de travail, n° F1907. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

GAZIER, Bernard, MINNI, Claude et PICART, Claude, 2016. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLa diversité des formes d’emploi. [online]. July 2016. Cnis, rapport de groupe de travail, n° 142. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

GOUX, Dominique, 2003. Une histoire de l’Enquête Emploi. In: Économie et Statistique. [online]. 1st July 2003. INSEE. N° 362, pp 41-57. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

INSEE, 2021. L’enquête Emploi se rénove en 2021 : des raisons de sa refonte aux impacts sur la mesure de l’emploi et du chômage. [online]. 29 June 2021. INSEE Analyses, n° 65. [Accessed 29 June 2021].

ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DU TRAVAIL (OIT), 1982. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletRésolution concernant les statistiques de la population active, de l’emploi, du chômage et du sous-emploi. [online]. 1st October 1982. Treizième Conférence internationale des statisticiens du travail. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DU TRAVAIL (OIT), 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletRésolution concernant les statistiques sur les relations de travail. In: Vingtième Conférence internationale des statisticiens du travail. [online]. 10-19 October 2018. Genève. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

RAZAFINDRANOVONA, Tiaray, 2015. La collecte multimode et le paradigme de l’erreur d’enquête totale. [online]. 27 March 2015. INSEE. Documents de travail, Méthodologie statistique, n° M2015/01. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

SIGNORE, Marina, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletMixed-Mode Designs for Social Surveys – MIMOD. Final methodological report summarizing the results of WP 1-5. [online]. 26 March 2019. Eurostat et Istat. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

SILLARD, Patrick, FAIVRE, Sébastien, PALIOD, Nicolas et VINCENT, Ludovic, 2020. Pour les enquêtes auprès des ménages, l’Insee rénove ses échantillons. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 29 June 2020. INSEE. N° N4, pp. 81-100. [Accessed 11 June 2021].

VINCENEUX, Klara, 2018. Mode de collecte et questionnaire, quels impacts sur les indicateurs européens de l’enquête Emploi ? [online]. 4 October 2018. INSEE. Documents de travail, Direction des Statistiques Démographiques et Sociales, n° F1804. [Accessed 11 June 2021].