Courrier des statistiques N6 - 2021

The permanent demographic sample (échantillon démographique permanent – EDP): in 50 years, the EDP has really grown!

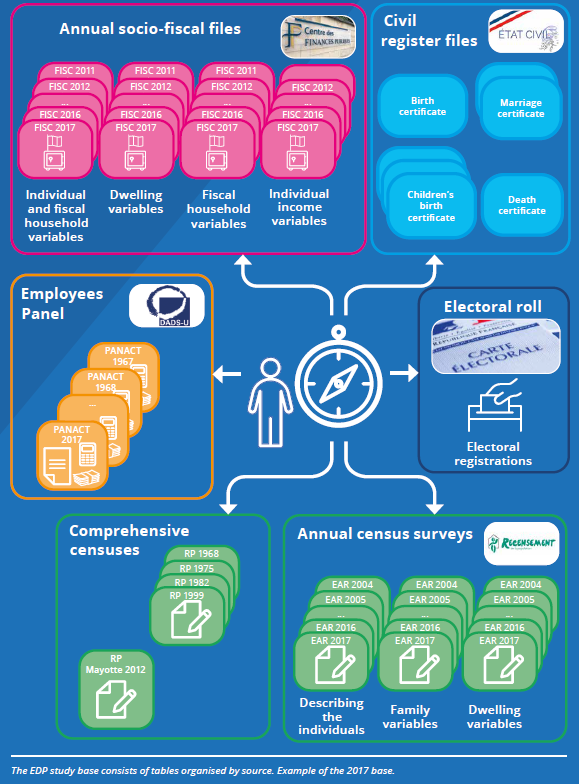

For more than fifty years, the permanent demographic sample (known as “EDP”) has been accumulating socio-demographic information for a sample of individuals representative of the population living in France. For each of these individuals, the EDP is enriched each year with data from the census, civil status, the electoral register and, more recently, employment data for salaried employees and tax data (income tax return and housing tax). This will soon be followed by the addition of data on the self-employed, and progress on the health side to evaluate the national health strategy.

The EDP currently tracks 3.7 million individual trajectories, including more than 200,000 over 50 years. It is a unique source for the study of geographical mobility over a long period, but also of changes in living standards in connection with family or professional events experienced, such as couples breakdowns or the transition to retirement. The inclusion of the standard of living in the EDP, in addition to the usual socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, socio-professional category, diploma, family situation) has further extended the field of study with this panel.

As a rare panel of individuals in the general population, the EDP has been able to adapt to changes in the sources it is based on. The transition from comprehensive census to census surveys in the mid-2000 s was an opportunity to broaden the sample size and integrate new comprehensive (tax data) or panel (employees) sources.

- Originally, the civil register and census for those born in the first four days of October

- Switching to 16 days to adapt to the continuous census

- With fiscal data, the EDP has regained its comprehensive nature...

- Box 1. What information is available in the EDP?

- … and is enriched annually with data on income and standard of living

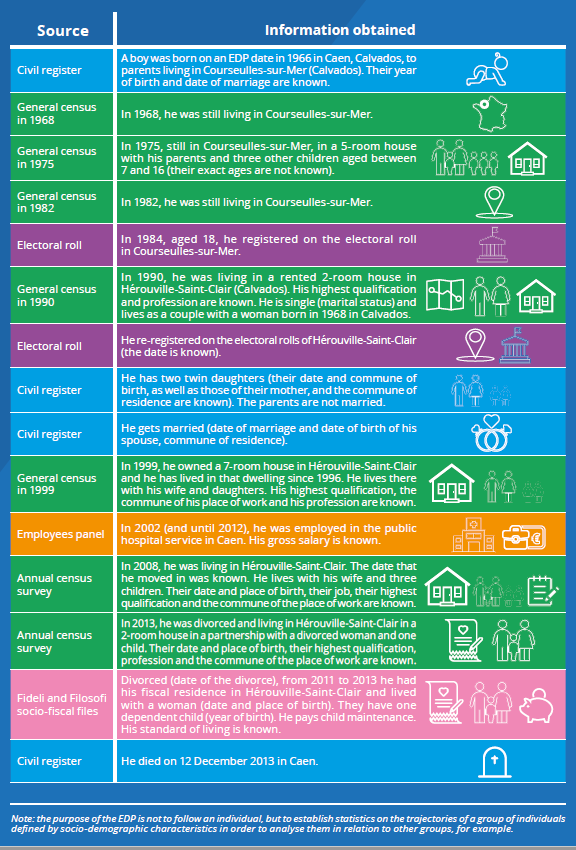

- Box 2. A fictional example of an individual trajectory

- Box 3. What happened to the people included on the census in 1968?

- Building your population of interest…

- Box 4. Panel monitoring requiring a unique and unvarying identifier

- … knowing how to use weightings

- Access to the data has a strict framework

- Box 5. The legal framework of the EDP in a nutshell

- Ongoing and future projects

- Legal reference

The permanent demographic sample (échantillon démographique permanent – EDP) was created in 1968 at INSEE from the compilation of data from the population censuses and civil register. The aim was to set up a new tool for the analysis of geographical mobility and social trajectories (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSautory, 1988), such as social differentials in mortality, professional trajectories over a long period or the trajectory of immigrants (professional mobility and acquisition of French nationality, for example).

Several approaches are possible to build up trajectory data: surveying people at a given time by asking them questions about their past career (retrospective survey, calling on the memory of the respondents); interviewing the same people several times to gather information over the years (but with the difficulty of finding people again to re-interview them, and with attrition therefore increasing over the years); or, like the EDP panel, gathering data collected elsewhere over the years.

Since its inception, the EDP has used administrative data and population census data, making it a particularly cost-effective system: no collection costs and no response burden on respondents. The sample can therefore be large in size, without attrition or memory bias. A very simple sampling criterion was used: date of birth. This simplifies the implementation of the panel and thus its sustainability.

With no memory effect or attrition, the EDP is also unique in its size (currently 3.7 million people), its historical depth (50 years of data for more than 200,000 people), and in the diversity of its sources (civil register, census, then electoral register and socio-fiscal data).

Over 50 years, the EDP has had to adapt to the sometimes significant changes in the data sources; the panel has also been able to integrate new data, which have enriched the studies, but have also made its use more complex.

Originally, the civil register and census for those born in the first four days of October

The people included in the EDP are those born on certain days of the year, known as “EDP dates” and established by decree since 2014. Initially, it was people born on the first four days of October. The first source used to start the panel was the 1968 census, supplemented by civil register data (births, deaths and marriages).

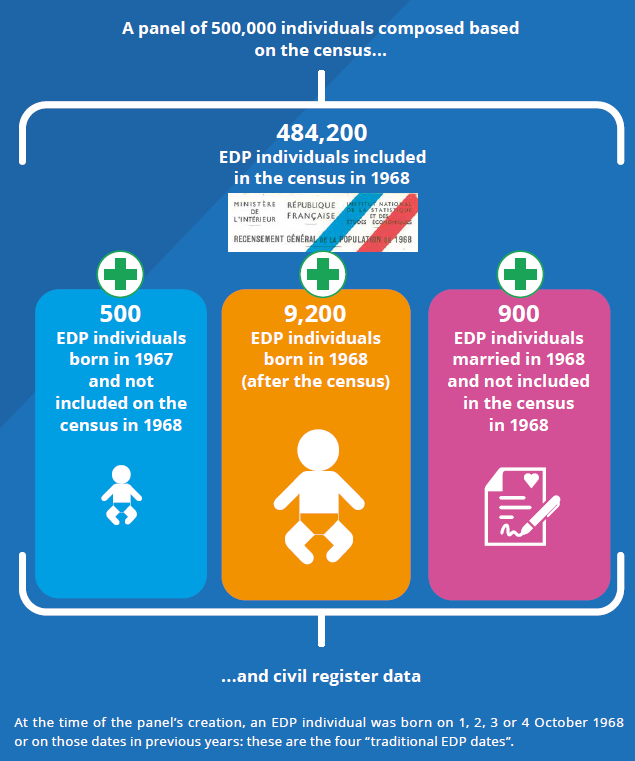

In 1968, the year in which the EDP was created, 500,000 people were included in this panel (Figure 1):

- 484,200 people included in the census in 1968 and born on 1, 2, 3 or 4 October (regardless of their year of birth);

- 9,200 people born on 1, 2, 3 or 4 October 1968, for whom the birth certificate was available in the civil register. They were not included in the census in 1968, which took place in March 19681, before they were born;

- 900 people added through the marriage section of the civil register (6,900 people born on 1, 2, 3 or 4 October got married in 1968, of whom 6,000 were included in the census in 1968);

- and 500 people born in 1967 but not included in the census in 1968 (of the 8,300 birth certificates of children born on 1, 2, 3 or 4 October 1967, 7,800 were for people already included in the EDP thanks to the 1968 census).

Figure 1. The EDP on its inception in 1968

If the panel had been limited to people born in 1968, it would have taken many years

to study trajectories. To avoid this issue, the sample included people of all ages

from the start. The panel was then enriched each year with people born on one of the

four reference days during the year in France, using information collected in civil

register entries and information recorded in successive census bulletins. Thus, the

base was close to a representative sample at 1/100th (4 days/365 days) of the population

residing in France (Couet, 2006).

Since its creation, the sample has been renewed by births or by the arrival of new people in France. If they were born on an EDP date, they join the EDP on the time of a census or an event recorded in a civil register entry (Couet, 2006). In contrast, the tracking of an individual ends, in effect, in the event of death or departure abroad. However, the traces of this individual remain in the sample with the details of the demographic events that marked their journey while in the country, and we can thus compare the trajectories of different cohorts at any time.

Switching to 16 days to adapt to the continuous census

The population census is primarily used to establish the number of inhabitants of each administrative district (establishment of the so-called legal populations), but it is also a privileged source for describing the population (sex and age, as well as highest qualification, social category, family configurations, etc.): as such, this source is fundamental for the EDP.

The method used for the census has changed: having been a comprehensive census every seven to ten years until 1999, it became annual in the early 2000s and is now based on a survey. Since 2004, annual census surveys (enquêtes annuelles de recensement – EAR) have thus been carried out on a sample of addresses. The consequence for the individuals included in the EDP is that they are no longer included in the census at the same time; for a given year, only one in seven individuals is present in the sample of the census survey.

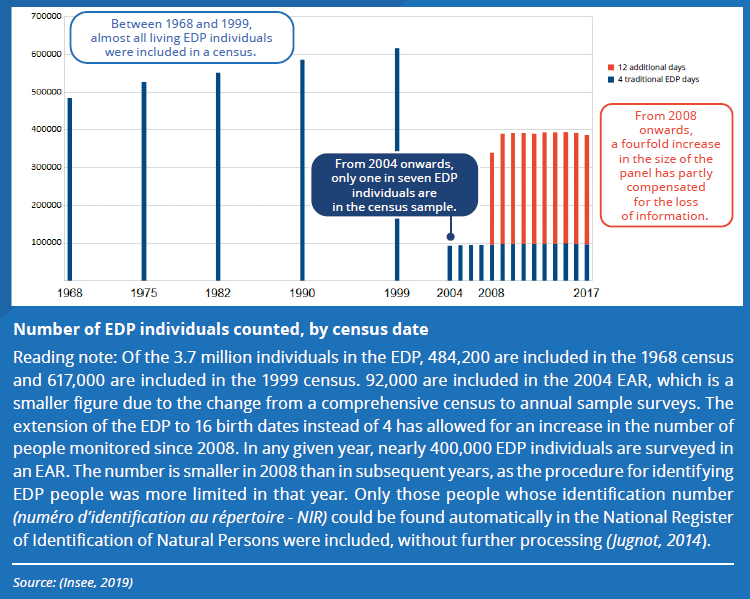

To compensate for the deterioration of the quality of the estimates due to the reduction of available data in a single year, the sample size was increased considerably: the number of EDP reference days was increased from 4 to 16 (Figure 2). This increase was not retroactive, as personal data are not kept in the census files.

The increase in the number of “EDP dates” was deliberately spread over the year, to improve the analysis of trajectories that may be affected by the seasonality of births (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletCNIS, 2006). Since 2008, the monitoring of the EDP panel has therefore concerned people born in the first four days of each quarter, with a tweak so as to avoid 1 January. The “EDP individuals” are people born on one of the following 16 dates: from 2 to 5 January, from 1 to 4 April, from 1 to 4 July, or from 1 to 4 October (with the latter four dates being the “traditional EDP dates”).

The increase of the panel to 16 days is not the only innovation put in place to compensate for the end of the comprehensive nature of the census. The EDP turned to another comprehensive source: socio-fiscal data.

Figure 2. The switch to 16 days makes it possible to partly offset the impact of the new census

With fiscal data, the EDP has regained its comprehensive nature...

Initially, the EDP compiled data from the civil register and population censuses. In 2008, it was enriched with data from the electoral register (dates of registration on electoral rolls, dates of removal from the roll, communes of registration), then from the “all employees” panel (which describes the history of salaried employment and remuneration, since 1968) and socio-fiscal data with Fidéli (demographic files on dwellings and individuals) and Filosofi (localised social and fiscal file) (Box 1).

The integration of fiscal data into the EDP has restored the comprehensive nature that it had lost when the population census method was changed. The fiscal data provide annual information for all individuals born on one of the EDP dates, including information on:

- the dwelling (location and characteristics of the dwelling);

- and on family circumstances (as this affects the marginal tax rate).

This therefore compensates for the fact that this type of information can no longer be collected via the census in a given year for all individuals.

The integration of socio-fiscal data into the EDP has undoubtedly been its biggest advance in recent years. These comprehensive administrative data come from the declarations used to calculate income tax and housing tax, supplemented by data on social benefits. They are used for statistical purposes and allow the EDP to enrich the areas covered by introducing the standard of living, a key variable in many socio-economic analyses.

… and is enriched annually with data on income and standard of living

While the statistical use of fiscal data outside the EDP only allows for individual monitoring of standard of living over two successive years, the integration of data from the Fidéli and Filosofi systems into the EDP now allows for monitoring over a longer period.

This panellisation of fiscal data since the 2011 tax returns (income for 2010), for the sample of people born on an “EDP date”, opens up a wide range of research possibilities. In this respect, an example is a recent study on the evolution of the standard of living of retirees (Abbas, 2020): at this time of pension reform debate, this analysis sheds light not only on the financial circumstances of retirees in the year of their retirement, but also on the evolution of their standard of living in the three years preceding retirement and the three years following it. It thus highlights the deterioration of living conditions for some people at the end of their career and the improvement of their financial situation after retirement, particularly for the least qualified retirees. This groundbreaking study would not have been possible without the EDP: it combines social characterisations (census data) and knowledge of resources over the years (panel fiscal data), which are only available in the EDP.

The individual trajectories monitored in the EDP have thus been expanded (Box 2).

The introduction of comprehensive socio-fiscal data has also enabled unprecedented new studies on family circumstances following the breakdown of a relationship, as the data allowing such approaches are rare, as highlighted by the CNIS (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletThélot et al., 2016). This is the case for the study on family housing in the year of a couple split and in the following years (Durier, 2017). Or analyses of changes in standards of living after a break-up, which show a sharp drop, on average, for women in the year of the break-up and a subsequent “recovery” in the following years (Costemalle, 2017), an improvement that is observed especially for parents who quickly form a new couple (Abbas and Garbinti, 2019).

The strength of the EDP also lies in the size of its sample: the study on the standard of living after a separation was thus adapted for the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region (Balouzat and Labosse, 2020), which would not have been possible with a smaller national sample.

The diversity of the sources that form its input, the potential geographical detail of the analyses thanks to the size of the sample and the historical depth of monitoring over 50 years (Box 3), the EDP is an essential source for panel studies: nearly 60 research teams are currently working based on these data (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletCASD, 2021). However, in contrast, this richness is accompanied by greater complexity in using the data.

Box 3. What happened to the people included on the census in 1968?

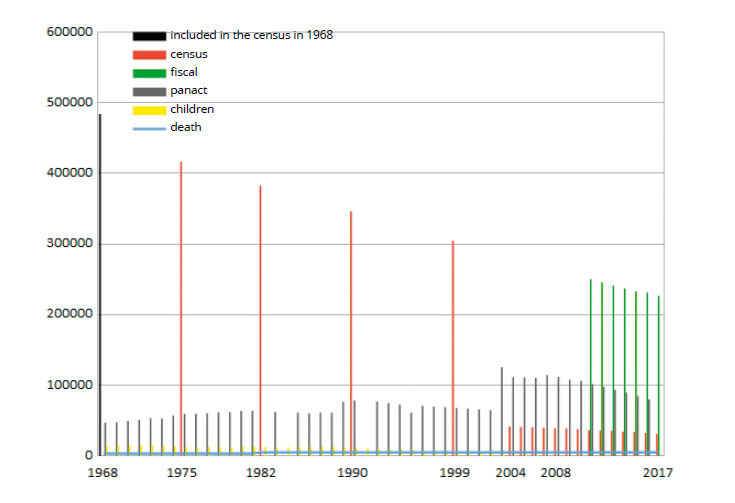

484,200 people born on 1, 2, 3 or 4 October, regardless of their year of birth, and included in the census in 1968, are tracked in the EDP. Over the years, they are present in the labour market, have children, are included in censuses, and some die:

- for 416,900 (86%) of them, statistical information is available from the 1975 census;

- for 346,200 people, data is available from the censuses in 1968 and 1999, to describe their trajectories over 30 years;

- the number of people found in the censuses after 1968 decreases over the years, as there are deaths and potential migrations;

- it drops sharply with the switch from comprehensive censuses to annual census surveys,due to the fact that data are now collected on a sample of the population: thus, for 41,600 individuals in the EDP panel who were included in the census in 1968, information is available from the 2004 annual census survey (EAR) and, for 31,400 of them, data is available from the 2017 EAR, the most recent year integrated into the EDP to date. However, there are many more people for whom there is information from the fiscal data: 226,700 people included in the census in 1968 also have statistical information about them in the EDP from the 2017 fiscal data, with statistical monitoring over almost 50 years.

The cohort approach can also be carried out by year of birth. In the same way, we can follow the lives ofthe 9,200 people born on 1, 2, 3 or 4 October 1968 based on the event tracked in the EDP.

Note: the number of children born with at least one parent born on an EDP day and included in the census in 1968 is estimated by multiplying by 2 the number of children born to EDP parents born on 1 or 4 October, to take account of collection gaps (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDurier, 2018).

Coverage: individuals born between 1 and 4 October (regardless of year) and for whom statistical information is available is available in the EDP from the 1968 census.

Source: (INSEE, 2019).

Building your population of interest…

The EDP allows individual pieces of information from multiple sources to be cross-referenced: for example, mortality (civil register data) can be studied by highest qualification (census), social category (census or all employees panel) and standard of living (fiscal data). However, the richness of the information is matched by the complexity of using the data: thinking about how to build your population of interest and whether or not to weight the data is a prerequisite for conducting a study based on the EDP. These prerequisites mean that the EDP is aimed at research officers or researchers who are comfortable with using data and have solid statistical skills, so as to avoid the introduction of bias into the results and analyses.

It is by combining information from the various sources integrated into the EDP that each research officer builds their population of interest and the data needed for their study (Box 1). They must then make use of various statistical tables in the EDP’s study database (Figure 3), which are connected by a common identifier (Box 4).

For example, in order to estimate life expectancies by standard of living, social category and highest qualification, a study which was carried out for the first time in 2018 thanks to the integration of fiscal data into the EDP, (Blanpain, 2018a), it was necessary to select people included in the census (highest qualification and SC), for whom civil register data (vital status) and fiscal data (standard of living) were found. The formation of its study base required prior expertise. The author has compared the magnitude of social differences in mortality (Blanpain, 2016) according to whether the social category is taken from the census or from the all employees panel (Costemalle, 2016). They assigned a standard of living based on income variables when information on the standard of living was not available. This is indeed the case for people not residing in ordinary housing for example, who are often elderly, and could therefore have an impact on the measurement of mortality by standard of living (Blanpain, 2018b). The author also compared their target population to other data to verify that the population of interest they had selected in the EDP was representative of the entire study population (comparison of life expectancies estimated using the EDP to those derived from population censuses (Blanpain, 2018b)) and to be able to readjust the selected population if necessary.

Once the population has been selected in the EDP, the question arises as to whether it represents the general population well, and thus the question of weightings.

Figure 3. As it becomes a richer source of information, the EDP becomes more complex to use

Box 4. Panel monitoring requiring a unique and unvarying identifier

From the outset, the longitudinal tracking of the people included in the EDP has been based on the identification number (NIR) in the National Register of Identification of Natural Persons. This identifier is unique and unvarying*. The people included in the sample tracked in the EDP are initially identified on the basis of their identity traits (surname, forename, sex, date and place of birth (Jugnot, 2014)): the aim is to use this information to find their NIR, and then to enrich their trajectories in the panel. For sources, such as the “all employees” panel, which already contain the NIR, this identification procedure is obviously not necessary. The NIR is only used for EDP production purposes, and surnames and forenames are not retained once identification has been completed.

The files made available to research officers and researchers for statistical purposes do not contain the NIR, but only a dissemination identifier which cannot be used for personal identification (which therefore does not provide information on the person). This dissemination identifier allows them to perform matching between the different EDP databases.

*Strictly speaking, the NIR can be changed in very rare cases (change of gender, for

example, which would change the first digit of the NIR).

… knowing how to use weightings

The switch from the comprehensive census to census surveys has introduced a new practice for studies carried out based on the EDP: weightings. The selection of dates of birth adopted in the EDP does not bias the analyses (within the limits mentioned above). Only a scaling factor was sometimes used to give orders of magnitude of the numbers involved (e.g. multiplying the numbers involved in the EDP by 365/4 or 365/16 depending on the years involved). However, estimating distributions or coefficients in econometric models did not always require the use of weights: all individuals had the same weight.

Yet, since 2004, the drawing of the sample for the annual census surveys (EARs) has differentiated between small and large communes: this makes it essential to use the weightings associated with the EARs in the EDP when they are used to define the population of interest. Weighting variables thus appeared in the EDP when the census stopped being comprehensive in nature.

However, the EARs can also be used without using these weightings, for example if this source is only used to supplement other data by adding additional variables.

Thus, in the study of the evolution of the standard of living of those who retired in 2013 (Abbas, 2020), an analysis is conducted by highest qualification. The population of interest was defined based on fiscal data and the declaration of income in the form of pensions. The information for these people was supplemented by the highest qualification level found in one of the EARs available in the EDP. There is then no reason to take into account the EAR weightings in this case, once it has been verified that the population for which a highest qualification level could be linked does not differ from the total target population (age, standard of living, etc.).

However, the richness of the data contained in the EDP has made its use more complex. This is why an EDP usage group was created by INSEE in 2015. It brings together research officers and researchers to discuss the new features added to the EDP and the work carried out based on this panel.

Access to the data has a strict framework

The EDP contains increasingly precise information on the individuals who make up the panel (Box 1), but it contains no personal data that would allow them to be identified directly. However, the repetition of information over time makes these data more sensitive to the risk of non-compliance with anonymisation criteria. Indeed, if we know a person whose date of birth corresponds to an EDP date, the cross-referencing of their other known characteristics with the information contained in the panel could lead to their identification in the panel, the probability of which is higher when the information is repeated over time than if we only have characteristics as at a given date. There is therefore a risk of learning more information about that person than is already known, and thus a potential breach of confidentiality. For this reason, the formation of and access to EDP data are highly regulated (Box 5).

At INSEE, research officers can access the data in a dedicated area after a nominative request, and they use the data in another area that is dedicated to processing.

For researchers, access is through the Secure Access Data Centre (Centre d’accès sécurisé aux données – CASD) (Gadouche, 2019), after the confidentiality committee has given approval for their project. This mode of access, which has been in force since 2010, has made it possible to develop uses of the EDP, on themes as diverse as territorial inequalities, the geographical mobility of immigrants in France, career paths and career transitions between the public and private sectors.

For the staff of the Ministerial Statistical Offices, the situation varies according to the security conditions for data access within the MSO. If necessary, they can also use the intermediary of the CASD.

Box 5. The legal framework of the EDP in a nutshell

The EDP is a processing of personal data carried out in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the French Law on Data Processing, Data Files and Individual Privacy. Therefore, it is subject to strict rules and measures to ensure the security and confidentiality of data.

Any person having access to the data is bound by statistical confidentiality. The data can be communicated to research officers and researchers, following approval by the Statistical Confidentiality Committee, pursuant to the provisions of French Law No 51-711 of 7 June 1951 on Legal Obligation, Coordination and Confidentiality in the Field of Statistics. However, identifying data, in particular the NIR, cannot be communicated under that framework.

Ongoing and future projects

The integration of socio-fiscal data has made it possible to conduct studies in a new field: changes in standard of living following an event, and in the years preceding or following that event. It drew the interest of researchers in the fields of economics and families: for example, the Big_Stat project, on massive statistical data to observe a mobile society (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletINED, 2021). It has also expanded the possibility of regional analyses (Lacour, 2018, Bertaux et al., 2019, Balouzat and Labosse, 2020, Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDherbécourt and Kenedi, 2020).

The expansion of the EDP sources will continue in the near future, with the non-employee panel, to cover broader employment trajectories: the EDP will include annual data on salaried employment and non-salaried employment, again over a long period, thus making it possible to analyse the trajectories between different types of employment over the course of a career, in connection with the socio-demographic characteristics of individuals (highest qualification, family, etc.). By accumulating information for more than 50 years now, the EDP has already made it possible to follow long trajectories, combining family life and career paths in particular.

The EDP is also opening up to a new field, within a specific legal framework: the field of health. In 2019, DREES provided the EDP with information from the French national health data system (système national des données de santé – SNDS): this source, which is managed by the National Health Insurance Fund, includes, in particular, health care consumption and medical causes of death, over 10 years, but without information on income, social background or professional and family circumstances. As health data are subject to specific procedures, this processing, which is authorised by the CNIL, is limited in time (5 years) (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDREES, 2020). It has a limited purpose, to evaluate the French national health strategy 2018-2022. It makes it possible to respond to questions regarding the assessment of social health inequalities, and to complement the analyses conducted with panel health data, but with few social descriptors. The first publication by DREES using the “EDP-health” thus offers a complementary analysis of the voluntary interruption of pregnancy and the frequency of abortions according to standard of living (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletVilain et al., 2020).

Finally, the emergence of new sources on professional careers and reasons for interruption offer avenues that are calling out to be investigated.

Legal reference

Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletArrêté du 6 août 2014 portant création d’un traitement automatisé de données à caractère personnel relatif à l’échantillon démographique permanent de l'INSEE. In: site de Légifrance. [online]. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

Paru le :02/10/2023

The Order of 6 August 2014, creating automated processing of personal data relating to INSEE’s permanent demographic sample (see the references to the regulations at the end of the article).

General population censuses (until 2004) were usually conducted in March.

Over a period of five successive years, the entire territory is covered by a census collection. The first results with the new method are those for 2006, which combine the surveys from 2004 to 2008 (Godinot, 2005).

One in five small communes (fewer than 10,000 inhabitants) is subjected to a comprehensive census each year, together with 8% of addresses in large communes. In total, around one in seven inhabitants is included in the census in a given year.

In practice, the switchover date varies depending on the source: 2004 for the civil register, 2008 for the EARs, 2002 for the “all employees” panel; 2011 for fiscal data (income received in 2010) and backcasting since the early 1990s for electoral registrations.

1 January was excluded, as this is too often the date used when the date of birth is unknown (INSEE, 2019).

The integration of fiscal data into the EDP was also in response to recommendations by the CNIS (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletChaleix and Lollivier, 2004).

Aside from a one-off study carried out with monitoring over 5 years (Bonnet, Garbinti and Solaz, 2015).

Longitudinal studies on career paths can be carried out using panels of employees or non-employees. However, the EDP also includes socio-demographic data, such as on family circumstances.

Pour en savoir plus

ABBAS, Hicham et GARBINTI, Bertrand, 2019. De la rupture conjugale à une éventuelle remise en couple : l’évolution des niveaux de vie des familles monoparentales entre 2010 et 2015. In: France, portrait social, édition 2019. [online]. 19 November 2019. INSEE. Pp. 99-113. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

ABBAS, Hicham, 2020. Des évolutions du niveau de vie contrastées au moment du départ à la retraite. [online]. 12 February 2020. Insee Première, n°1792. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

BALOUZAT, Bruno, LABOSSE, Aline, 2020. Lors d’une séparation, les femmes basculent plus souvent dans la pauvreté que leur conjoint. [online]. October 2020. Insee Analyses Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, n°103. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

BERTAUX, Frédéric, BOUSSAD, Nadia et SAGOT, Mariette, 2019. En quinze ans, la moitié des Franciliens résidant dans des espaces « pauvres » ont changé de commune. [online]. 30 September 2019. Insee Analyses Île-de-France, n°104. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

BLANPAIN, Nathalie, 2016. L’espérance de vie par catégorie sociale et par diplôme – Méthode et principaux résultats. [online]. 18 February 2016. INSEE. Documents de travail, Direction des Statistiques Démographiques et Sociales, n°F1602. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

BLANPAIN, Nathalie, 2018a. L’espérance de vie par niveau de vie : chez les hommes, 13 ans d’écart entre les plus aisés et les plus modestes. [online]. 6 February 2018. Insee Première, n°1687. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

BLANPAIN, Nathalie, 2018b. L’espérance de vie par niveau de vie – Méthode et principaux résultats. [online]. 6 February 2018. Documents de travail, Direction des Statistiques Démographiques et Sociales, n°F1801. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

BONNET, Carole, GARBINTI, Bertrand et SOLAZ, Anne, 2015. Les variations de niveau de vie des hommes et des femmes à la suite d’un divorce ou d’une rupture de Pacs. In: Couples et familles. [online]. 16 December 2015. Insee Références, pp. 51-61. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

CASD, 2021. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEDP : Échantillon Démographique Permanent. In: site du Centre d’accès sécurisé aux données. [online]. Les sources de données déjà disponibles au CASD. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

CHALEIX, Mylène et LOLLIVIER, Stéfan, 2004. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletOutils de suivi des trajectoires des personnes en matière sociale et d’emploi. [online]. June 2004. Cnis, Mission Panels, note n°98/B010, class. 1.5.91. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

CNIS, 2006. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDynamique et trajectoires. Compte rendu de la séance du 3 avril 2006. [online]. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

COSTEMALLE, Vianney, 2016. Catégorie sociale d'après les déclarations annuelles de données sociales et catégorie sociale d’après le recensement : quels effets sur les espérances de vie par catégorie sociale ? [online]. 18 February 2016. INSEE. Documents de travail, Direction des Statistiques Démographiques et Sociales, n°F1603. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

COSTEMALLE, Vianney, 2017. Formations et ruptures d’unions : quelles sont les spécificités des unions libres ? In: France, portrait social, édition 2017. [online]. 21 November 2017. INSEE. Pp. 95-111. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

COUET, Christine, 2006. L’échantillon démographique permanent de l’Insee. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. INSEE. n°117-119, pp. 5-14. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

DHERBÉCOURT, Clément et KENEDI, Gustave, 2020. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletQuelle influence du lieu d’origine sur le niveau de vie ? [online]. 12 June 2020. France Stratégie. La note d’analyse, n°91. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

DREES, 2020. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletL’EDP-Santé : enrichissement de l’échantillon démographique permanent par les données du système national des données de santé (SNDS). [online]. 8 July 2020. Direction de la recherche, des études, de l'évaluation et des statistiques. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

DURIER, Sébastien, 2017. Après une rupture d’union, l’homme reste plus souvent dans le logement conjugal. [online]. 17 July 2017. Insee focus n°91. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

DURIER, Sébastien, 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletUne nouvelle source de données sur la famille : l’EDP enrichi de données socio-fiscales. In: Observer, décrire et analyser les structures familiales. [online]. Édité par Nicolas Cauchi-Duval. Association internationale des démographes de langue française. Pp. 5-15. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

GADOUCHE, Kamel, 2019. Le Centre d’accès sécurisé aux données (CASD), un service pour la data science et la recherche scientifique. In: Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 19 December 2019. INSEE. n°N3, pp. 76-92. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

GODINOT, Alain, 2005. Pour comprendre le recensement de la population. [online]. Insee Méthodes hors série May 2005. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

INED, 2021. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBig_Stat. In: site de l’Ined. [online]. Institut national des études démographiques. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

JUGNOT, Stéphane, 2014. La constitution de l’échantillon démographique permanent de 1968 à 2012. [online]. 19 September 2014. INSEE. Documents de travail, Direction des Statistiques Démographiques et Sociales, n°F1406. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

LACOUR, Cédric, 2018. Les séparations : un choc financier, surtout pour les femmes. [online]. 16 October 2018. Insee Analyses Nouvelle-Aquitaine n°64. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

SAUTORY, Olivier, 1988. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletPlus de la moitié de la population a changé au moins une fois de commune en vingt ans. In: Économie et statistique. [online]. April 1988. INSEE. n°209, pp. 39-47. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

THÉLOT, Claude, BOURREAU-DUBOIS, Cécile, CHAMBAZ, Christine, 2016. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLes ruptures familiales et leurs conséquences : 30 recommandations pour en améliorer la connaissance. [online]. March 2016. Cnis, rapport de groupe de travail. [Accessed 30 May 2021].

VILAIN, Annick, ALLAIN, Samuel, DUBOST, Claire-Lise, FRESSON, Jeanne et REY, Sylvie, 2020. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletInterruptions volontaires de grossesse : une hausse confirmée en 2019. [online]. September 2020. Drees. Études et Résultats, n°1163. [Accessed 30 May 2021].