Courrier des statistiques N4 - 2020

The 2020 Socio-Professional Classification Continuity and Innovation, For Greater Use

On the release of the latest revision to the French Classification of Professions and Socio-Professional Categories (PCS), this article reconsiders those central but underrated subjects of official statistics: classifications, also sometimes known as nomenclatures. They are essential to statisticians in naming and organising the reality they have to describe and they help stabilize the cognitive and practical space. But over time, they must remain in step with the state of the world and make sense to the parties handling them.

The reform of the PCS illustrates the two key issues at stake in the periodic revision of classifications: the conflict between the need for an update, set against the wish to maintain a comparison over time; and their appropriation by users, whether they produce or make use of statistics. The chosen solution provides flexibility, combining continuity and innovation: it reaffirms the classification principles and keeps the historic socio-professional categories unchanged; but at the same time, it proposes additional categorisations for analysing social position, and an update to the detailed level of classification of professions. Based on a simplified coding system and educational presentation via a dedicated website, the updated PCS classification constitutes a complete system allowing a wider range of current and historic analyses of the world of work and the social structure.

- Statistical Classifications are not Abstract Edifices

- Classification Means Naming and Organising...

- ... Reflecting and Establishing Reality, in Different Ways

- The Mark of Time: Why and How to Update the PCS?

- Professions: Reaffirmed Principles and Updated Headings

- A Job Class Schema to Complement the Historic Categories

- Box 1. The Job Class and Subclass Schema

- Categorisation Packages, or Disruption to Continuity

- Box 2. Household PCS, a New Concept More Appropriate to Social Change

- Increasing Use Through a Simplified Coding Procedure...

- ... and Appropriation of the Classification thanks to a Dedicated Website

Classifications play a remarkable role in economic and social statistics. It would

be impossible to give an account of a perceptible reality that is too diverse to be

directly observed, measured and understood without the use of classifications. Like

the key indicators (of growth, prices, unemployment, etc.), they define the rudimentary

categories of the language of statistics: they are the cells of tables and bars in

charts. Classifications are therefore essential, like the words in a dictionary. And

yet they continue to be underrated.

Between the mathematical formalisations supporting them and the institutions that

champion them, they are “the obscure face of scientific and political work alike” (Desrosières, 2010). Just as mastering a language in practical terms does not presuppose

thorough knowledge of its grammar and etymology, so the effectiveness of classifications

does not require mastery of their principles and origin. It is even partly the opposite:

the success of statistical categories is due to their apparent obviousness. Their

names and the reality they denote must seem natural so that we can forget, at least

temporarily, the construction from which they stem.

Statistical Classifications are not Abstract Edifices

They are not unconnected with the ordinary or institutional categories (government, legal and scientific) that refer to the sometimes long history of human practices and compilations. As François Héran wrote (Héran, 1984), “[the statistician or demographer] works [...] on precut categories and ready-to-count elements, so can allow themselves to forget their genesis”. By establishing the conventions of equivalence, i.e. the categorisation rules demarcating the spaces where individual situations may be deemed equivalent, classifications follow the rhythm set by institutions and social norms. They are form-giving operations or “investments in forms” (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletThévenot, 1986), whose time horizon is measured in decades rather than years. They allow us to measure short or medium term changes, but cannot reflect structural transformations, which necessitate the revision of categories.

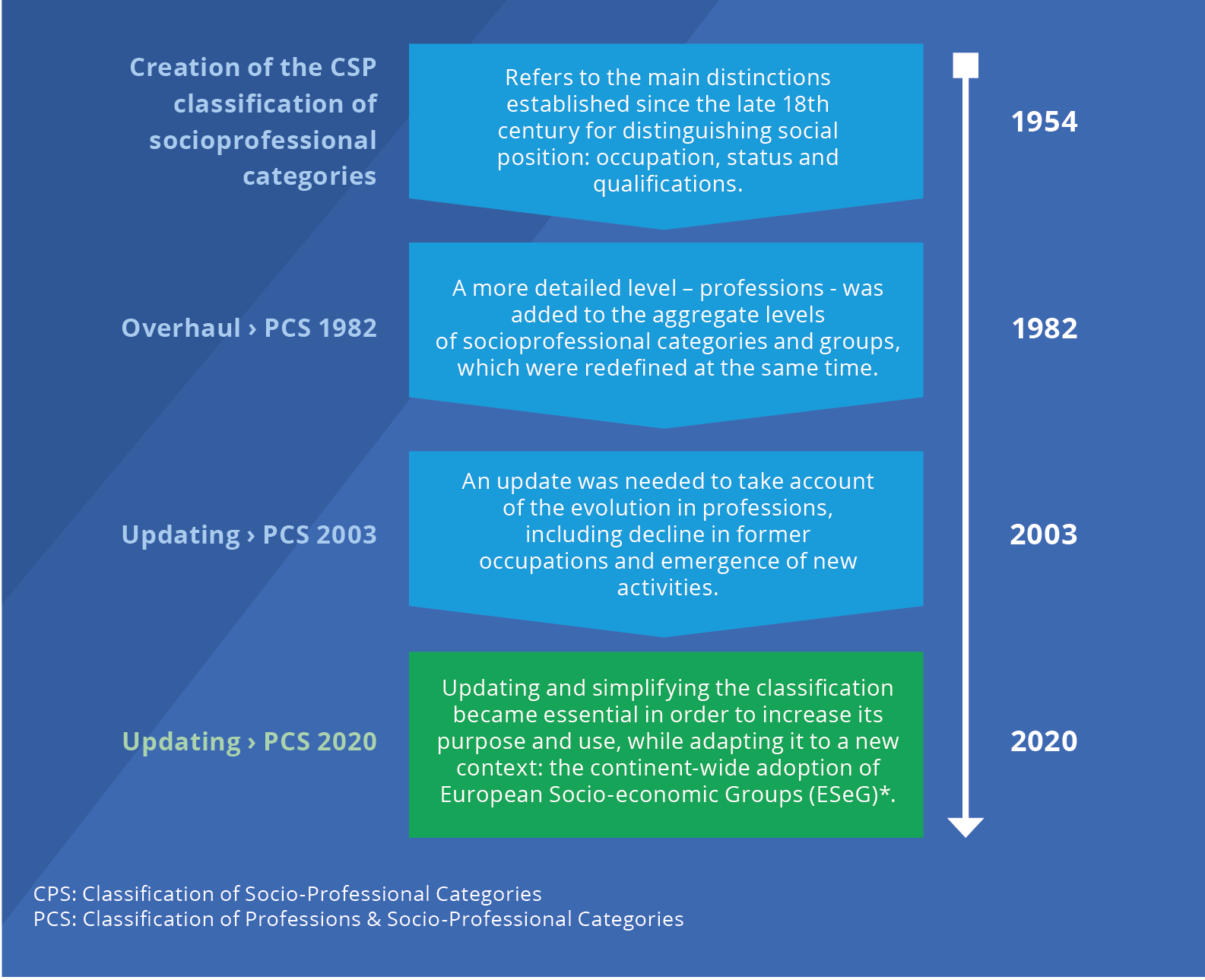

The Professions and Socio-Professional Categories (PCS) are emblematic of the consideration given to statistical classifications in France (Figure 1). An examination of their history, from their origin to their latest update (Desrosières, 1977; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAmossé, 2013; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAmossé, 2019), provides the opportunity to reconsider the complex subject that classifications more broadly represent, starting with scientific classifications, then gradually narrowing the focus and moving on to the statistical. In the case of the PCS, they pose two main challenges: their evolution, with the need of up-to-date grids set against the opposing wish for comparisons over time; and their appropriation by users, whether they produce or make use of statistics.

Figure 1. The Socio-Professional Classification: the Benchmark in France for Analysing SocialStratification, Social Classes and the Working World

* See (Meron et alia, 2016).

Classification Means Naming and Organising...

Nomenclature literally means a description of all the terms used in a given field (a science, technique, art, etc.). The word is derived from Latin roots: nomen (“name”) and calare (“to call”), giving the word nomenclator in Ancient Roman times (“a slave who told his master the names of the people he had to greet”) and nomenclateur in modern-day French (“a person who names things and living beings”). So, compiling a nomenclature, or classification, initially meant naming reality in all its diversity, with the terms having to refer to all the entities deemed relevant in describing a particular field. It was only later on, when the naturalists of the 18th century (Linnaeus, Buffon, etc.) had drawn up the first modern scientific classifications, that the idea took hold of the need for a method of organising names and entities.

Classification, which is the preferred term among English speakers, and taxonomy, another synonym for nomenclature that comes from the Greek word taxi meaning “order”, are both more indicative of this other dimension: the elements and information in a nomenclature must be classified and ordered. It entails grouping together the entities described by name while adopting a method or rules that reflect both the way in which reality itself appears to be organised, and the view one has of it.

The etymology reveals some of the issues raised by classifications. Alain Desrosières analysed these issues in the chapter on Classifying and Encoding in his work entitled The Politics of Large Numbers (Desrosières, 2010). In it, he describes the conflict between the two taxonomies of living beings proposed by Linnaeus and Buffon. The first is related to a divine order and is set up as a system: all of nature is to be found in tables there, according to the general features selected by Linnaeus, which are presented as an assertion of reality itself and are systematically used to distinguish between species, genera and families, etc. In the second, Buffon adopts a method where he constructs a representation of nature by selecting, step by step, the relevant traits to distinguish one species from another locally. By placing importance on the typical characteristics of common families of species and their names, Buffon’s method produces a nomenclature that can be described as natural, typical and nominalist, whereas the Linnaeus system is a logical, criterion-referenced and realistic classification.

This conflict, taking us back, respectively, to reasoning by example and by generalization, runs throughout the history of nomenclatures and classifications. As Desrosières noted, “the theoretical taxonomist is spontaneously drawn to the Linnaeus approach and suspicious of the Buffon approach”. Consequently, modern science has contributed to the development of systematic and theoretical approaches to compiling classifications; for example, in the late 18th century, Lavoisier’s Report on the need for reform and improvement of chemistry nomenclature was aimed at replacing the old designations derived from alchemy.

However, scientific advances do not all head in a single direction and they have their ups and downs. Some theories emerge while others decline. In science, but also in administration too and, more broadly, in economic, social and human activities as a whole, competing views develop over the course of history, providing multiple ways of thinking about and organising reality. They are limited in number, given the cognitive and practical costs entailed in the compilation and appropriation of such world representations. But the prospect of having at one’s disposal, within a given field, a single, unique classification that is founded on systematic criteria and related to a unified theory of reality often appears illusory. As the fruit of the sedimentation and hybridization of divisions with often local relevance, reliant on typical examples and on names taken from everyday language, classifications compiled over time show more similarities with Buffon’s method than with the Linnaeus system.

... Reflecting and Establishing Reality, in Different Ways

The plurality and hybridization of denomination rules and classification principles stem in particular from the history of statistical taxonomies. In this article, the latter denote classifications whose statistical implementation seems central, it being understood that any classification may be used for statistical purposes, that is to say, to count the entities categorized therein.

So, right from its initial adoption in the late 19th century, the International Classification of Diseases has referred in an interlinked way to two competing principles, demonstrating both the expected objectives in regard to knowledge of the causes of death, and the practical coding constraints: according to the first, topographical principle, pathologists categorize deaths according to the symptoms observed and their physical location; the second, aetiological principle, preferred by epidemiologists, presupposes identification of the disease that was the initial cause of death (Fagot-Largeault, 1990). At the time of writing, there are no fewer than five medical information classifications aimed at addressing the diversity of needs in regard to organising health knowledge and practices: these include classifications describing diagnoses (ICD), techniques used by health professionals (CCAM and CSARR), and medical devices and medication (LPP and ATC).

Different statistical classifications are also frequently to be found in the field of economics; for example, budget regulations stipulate that government accounts may be presented according to the issuing department or the department that is the beneficiary of the expenditure, but also according to the nature of the expense (staff, operational, etc.) or the corresponding operational area (or activity). Still in the field of economics, the history of the different branches of industry has revealed the multiplicity of ways of classifying economic activities since the 18th century (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGuibert, Laganier and Volle, 1971): so, over time, preference has been given, in turn, to rules based on the raw materials used, production techniques and product use which are the structuring principles still found set out within the French official classifications of activities and products (NAP).

The diversity of statistical classifications, or the principles on which they are based, can be explained by the complex link they maintain with the reality they represent. They cannot be considered neutral instruments or simple mirrors of a reality that exists outside the format they provide. They reflect it but also establish it: by allowing a move from singularity to generality, they serve as a means of reference to understand the world around us, as supports for formulating judgements, and as guides for taking decisions. Classifications thus help stabilize the cognitive and practical space, for a while at least. And they can do so in many different ways. As a result of negotiations between stakeholders, they are policy constructions which can follow several principles and be formalized in different ways: they may be autonomous or linked to others, continuous or discontinuous, flat or nested, hierarchical or not (Boeda, 2008).

These characteristics have been emphasized in particular by the comparative analysis of the socio-professional classifications in different countries and at different periods. From the scales describing socio-economic status or prestige discussed on the other side of the Atlantic, to the British hierarchical classification and the multi-dimensional non-ordered categories adopted in France, these classifications show there is no single way of expressing the structure of jobs and social positions. Moreover, the recent updating of the PCS in France demonstrates the two central challenges posed and which the rest of this article will illustrate: the potential conflict between stability and updating that is involved in the evolution of classifications; and their appropriation by a wide variety of users for a wide variety of purposes.

The Mark of Time: Why and How to Update the PCS?

The recent history of the French socio-professional classification attests to “the peculiar position of a tool of social representation that was ostensibly static amidst constant changes in the institution that managed it, the actors who used it, the social categories—everyday or legal—to which it referred, and, finally, the sociological theories that gave it a conceptual grounding and anchored its interpretation” (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAmossé, 2013). It is for that reason that each of its reworkings and successive updates have been preceded by a survey of its users. Their conclusions have been similar: the world changes, yet the categories do not lose all relevance. So, the work on producing an overview of the situation carried out prior to the latest update indicates that the classification continues to constitute “a ‘common language’ that is known and recognised in various professional worlds and a tool that meets a wide range of user expectations and objectives. ” (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletPenissat, Perdoncin and Bodier, 2018).

Admittedly, the model for representing professional hierarchies within companies was somewhat transformed with the development in the 1990s of the new system of “classifying criteria” as a grid format for collective bargaining agreements (note: these grids locate all jobs on a scale according to “classifying criteria” such as degree of autonomy, responsibility, etc.). Similarly, new rules for managing public sector employment and the reclassification into new administrative categories of several professions (school teachers, police officers, nurses, etc.) changed the job structure in the civil service and public sector. And yet these changes were gradual and partial: the traditional branches where there are many small businesses, such as construction, demonstrated attachment to the historic categories used in collective agreements, known as Parodi, that distinguish between the major groups referred to as “labourer”, “manager”, etc. Consultations prior to the last two updates helped to measure the real but limited scale of the changes that had affected the institutional job classification categories used as the foundation for the socio-professional classification. So, the prospect of a thorough revision of the classification in terms of its structure or principles was put off.

However, alongside the wish stressed by many users to keep the historic categories unchanged to allow comparisons over time, there was also demand for evolution. So the classic conflict arose between maintaining the categories for use in long series, and the need to update them to give an account of socio-economic changes. Justification for modifying the classification notably included the transformations in professions at the detailed level, such as the spread of digital technologies, the development of the transition to the green economy, and the convergence of occupations carried out by public sector employees and private sector employees. Broader changes were also mentioned, affecting, for example, the recomposition of the “manual” and “non-manual” basic worker groups (the “ouvrier” and “employé” group in French, and the need to express their segmentation by level of qualification), the hierarchy within the “manager” group, known as “cadre” in French (distinguishing senior management and clarifying the position of teachers), and a new demarcation and differentiation in regard to self-employed workers (where the “grey areas” of employment would be separated out).

To meet these partially contradictory expectations, the 2020 updating operation opted for an original solution. Firstly, the decision was taken to update the professions to provide an updated frame of reference for the world of work at the detailed level of the classification, while keeping the historic socio-professional categories unchanged at aggregate level to preserve their comparability over time. Secondly, a social categorisation was devised as an addition to the historic classification – the Job Class Schema – which provides a framework for analysing social positions that expresses the emerging divisions within the employment structure. As we will see, these developments respect the history and principles of the classification while ensuring some degree of flexibility in its possible uses.

Professions: Reaffirmed Principles and Updated Headings

Expanding on the principle of the statistical recording of social practices in classifying occupations that the classification has adopted since 1982 (Desrosières and Thévenot, 2002), the concept of profession, in the sense of the PCS, corresponds to the diversity of ways in which working activities are organised, established, qualified and described in their own professional world. It thus expresses not just the content of the work, but also its economic or institutional environment.

This summary concept refers to pragmatic sociology and the economics of convention, which have identified a multiplicity of ways of stating one’s occupation and organising work activities (Boltanski and Thévenot, 1991; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletKramarz, 1991). But it also echoes North American sociology of professions and more recent work on micro-classes (Grusky and Sørensen, 1998).

So, given its reaffirmed theoretical associations, the concept of profession in the PCS still seems appropriate to the French situation: institutional differences (for example by self-employed / employee status or by the public / private nature of the employer) continue to have a specific influence on objective work situations as on everyday representations (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletHugrée and De Verdalle, 2015; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletHugrée, Penissat and Spire, 2015). Profession in the PCS constitutes an additional approach, at least in regard to principles, to the one followed by the classification of occupations produced by the International Labour Organisation, which refers to what the activity entails (tasks carried out, duties performed or skills used). In practice, the profession headings in the socio-professional classification correspond both to an activity and a professional context that can be identified through a set of specific descriptions, together with a combination of variables defining the work environment (status, number of employees, professional position and nature of employer).

While reaffirming these principles and taking as its basis an empirical examination of head counts and descriptions of existing professions, the finely detailed level of the classification (known as the P 2020) has been updated to express the dynamics of work environments and occupations and it now has fewer headings (310, compared with 486 previously).

The updated headings, whose size and construction are more consistent all over the classification, ensure a more balanced representation of male-dominated and female-dominated professions, as well as greater comparability between private sector and public sector professions, where the reality of the tasks performed is now also taken into account and not just the administrative position. The explicit definition of a new middle level (126 groups of professions, defined by the top three P 2020 positions) is also aimed at providing greater clarity as regards how the professions are organised and how they link up with the classification's aggregate categories.

The updated and reorganised version of the detailed level of the classification is also accompanied by a new level of analysis, more closely related to the work situations. This level corresponds to the descriptions of professions stated in the surveys. These are standardized as they are taken from a list of several thousand items used in the updated coding procedure (see below), and will allow examination of professional fields spanning the professional headings in the classification (though subject to access guaranteeing compliance with rules on statistical confidentiality and security of processing). So, as part of the updating process, four ad hoc groupings of professional descriptions were formed: teachers; digital professions; occupations in the green economy; and high level business leaders, managers and professionals (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAmossé, 2019).

A Job Class Schema to Complement the Historic Categories

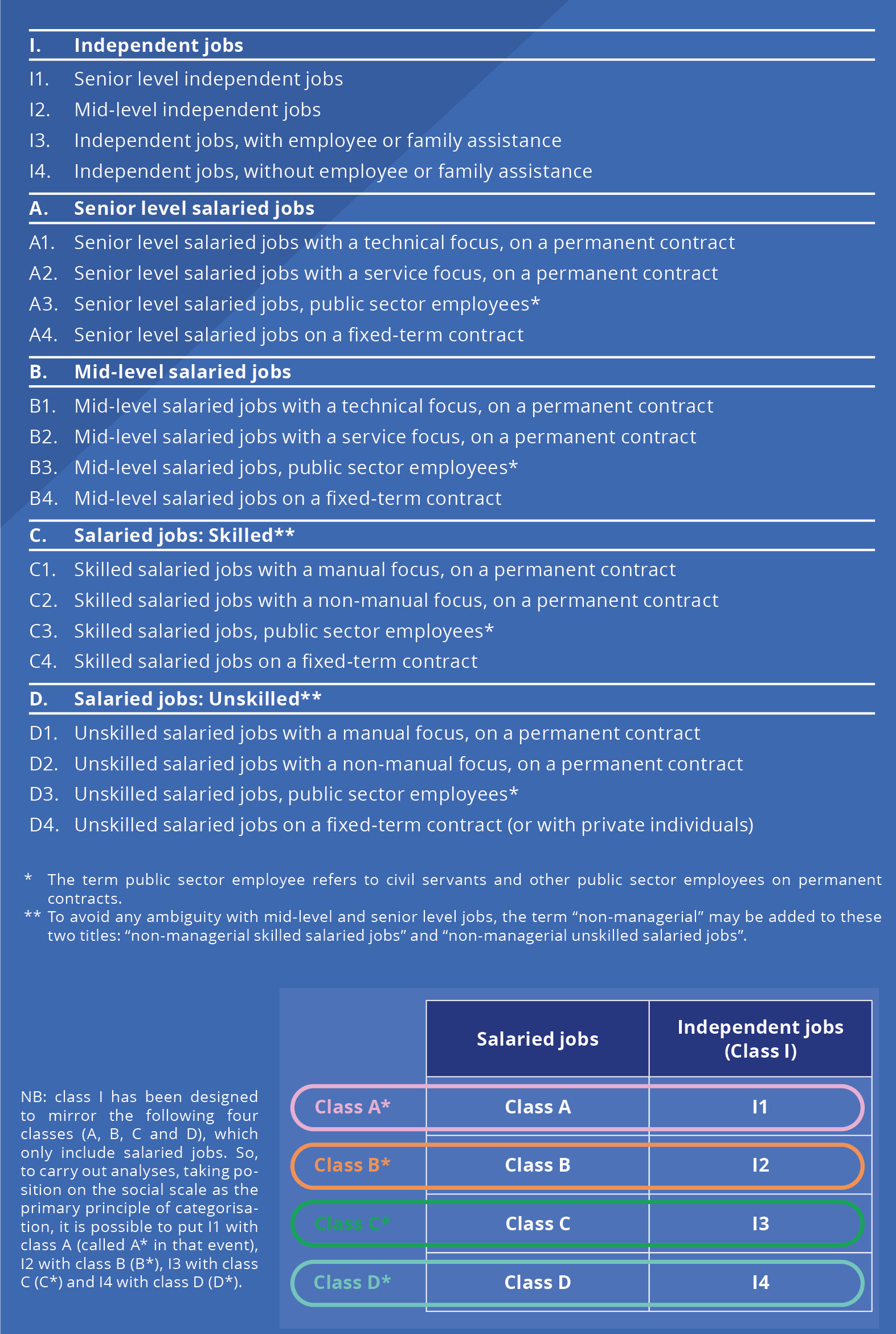

At the classification's aggregate level too, the updating process strove to address the conflict between continuity and disruption. As the socio-professional groups and categories only propose one relevant, albeit dated, way of representing society, a schema of job classes and subclasses has been devised.

Designed to be as clearly distinguishable as possible from the historic classification, this schema meets the need for a better representation of the divisions that are increasingly significant in the way jobs are structured and social positions determined: the distinction between self-employed and salaried workers, highly skilled and unskilled workers, in stable or insecure jobs, in the public or private sector, and in a technical or tertiary occupation. The intention is thus to allow analysis of the transformation in working society that has been in progress for decades (Box 1).

The analyses carried out show that, in light of their qualifications, few professions merit being put into a different job class in comparison with the historic classification groups (“managers and intellectual professions”, “associate professionals and technicians”, “basic tertiary employees” and “labourer”). However, there is a clear distinction between a limited number of these professions and their historic groups, such as school teachers, who appear to be markedly more qualified than all the associate professionals and technicians (consequently in the job class schema, these professions are included in senior level salaried jobs). These analyses thus indicate not only that the socio-professional groups are far from having lost all relevance for expressing social stratification, but also that the job classes are more appropriate to the work done, from this perspective.

Other statistical operations, carried out to validate the Job Class Schema, confirm the relevance of the socio-professional groups and categories, which remain more strongly associated with the social origins and social positions of the spouse and geographic situations than the job classes (and the European socio-economic classification, the ESeG). The explanation for this situation can be found notably in the historically and sociologically typical symbolic categories at the top and bottom of the social spectrum, namely farmers and labourers, the liberal professions and business leaders. The Job Class Schema is better at expressing the diversity of situations in regard to age, marital/partner status, housing and income. It thus appears to be clearly complementary to the historic classification, by including head counts that are more balanced across the entire social spectrum (owing to more consistent grading by level of qualification) and giving a view of sections that were, up to now, under-represented or not represented at all, such as, for example, the public sector jobs and insecure jobs at each qualification level.

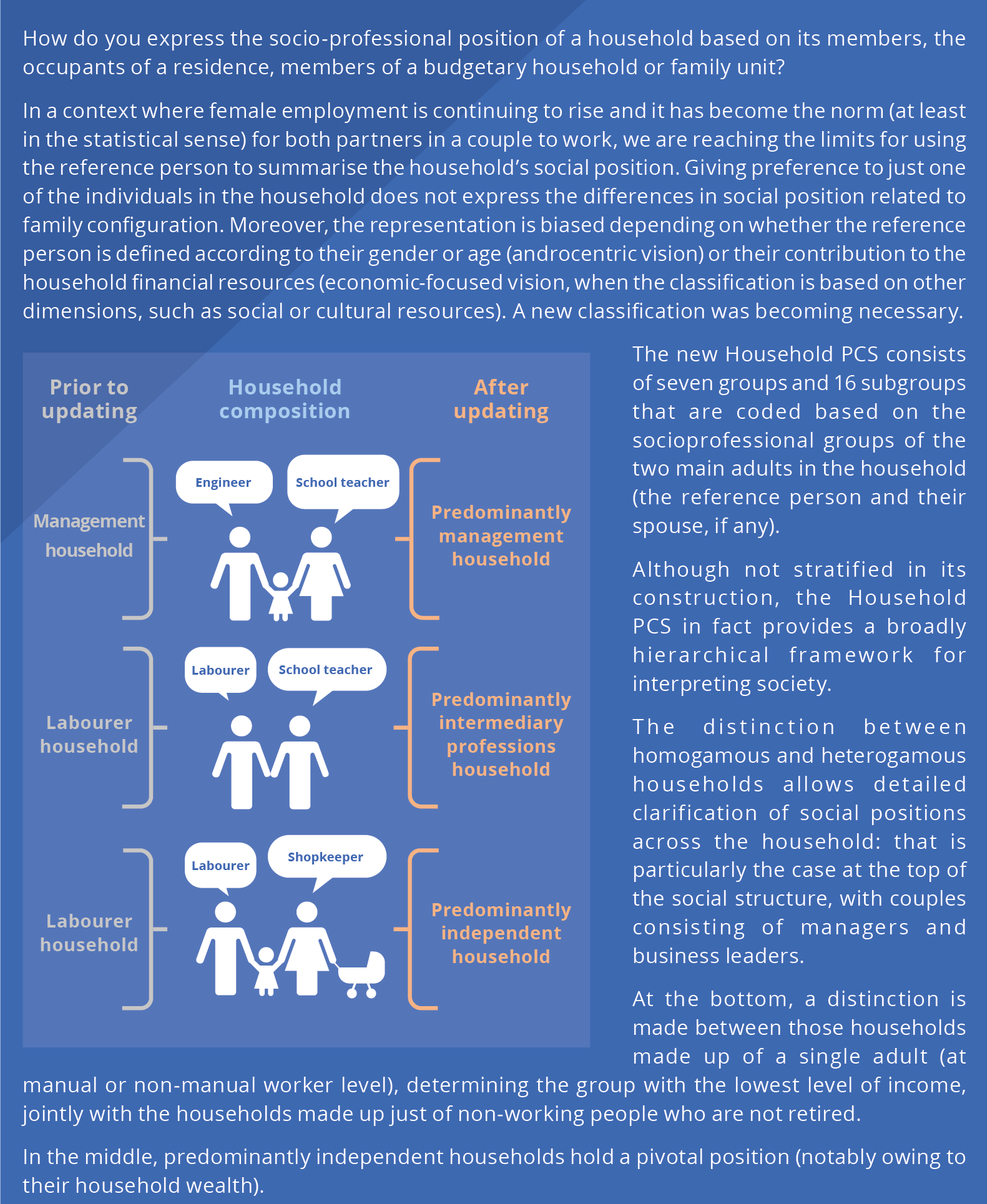

Categorisation Packages, or Disruption to Continuity

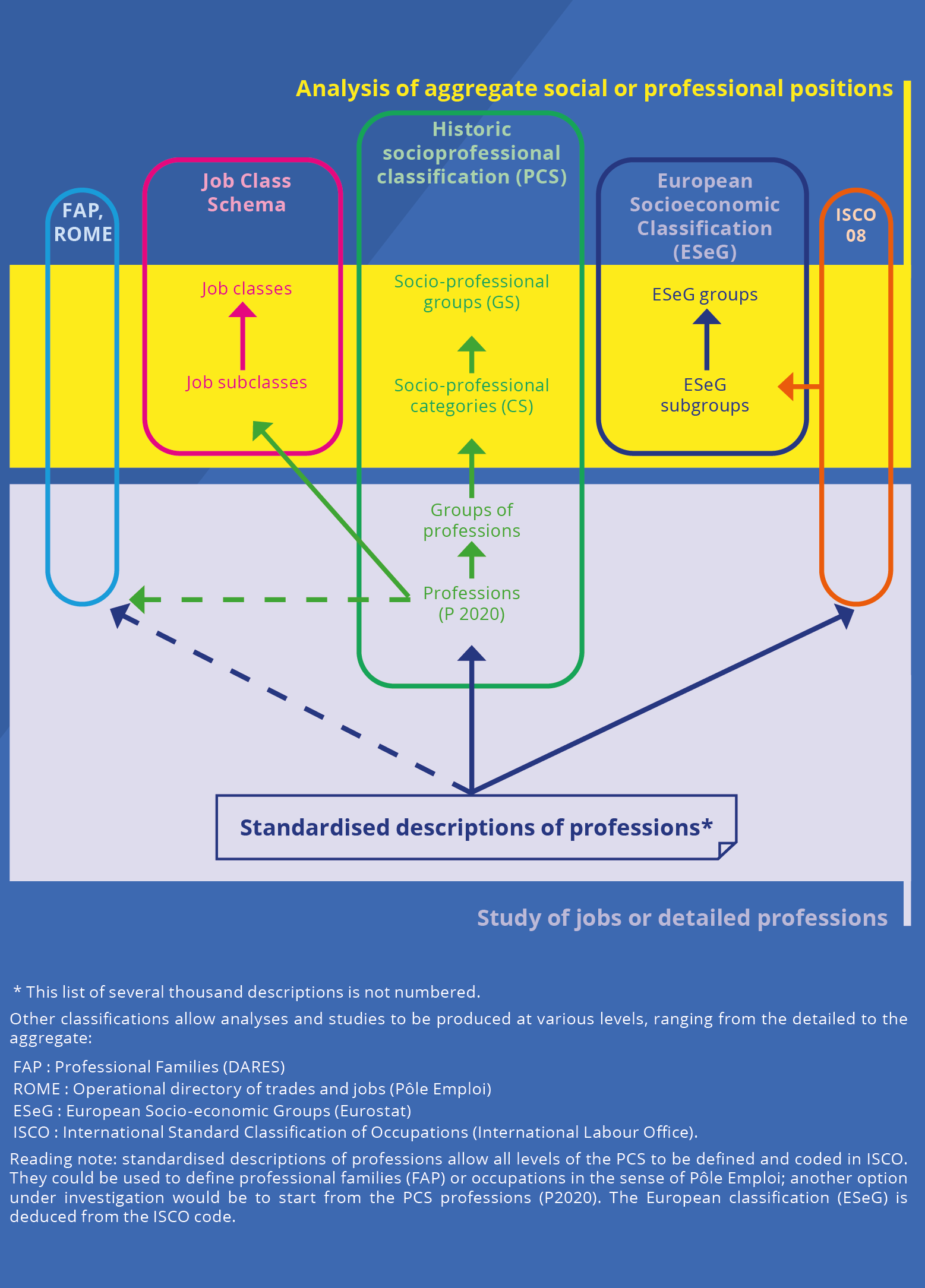

With the Job Class Schema, the classification reform offers an original solution to facilitate both comparisons over time and the updating of frameworks for analysing society. It thus offers a package of social categorisations linked to the socio-professional classification that will be able to address users’ different analytical issues: the historic groups and categories, whose sociological relevance has been confirmed, and which will continue to be particularly useful for historic and geographic analyses; all of the ESeG groups and subgroups, the primary purpose of which is to aid European-wide comparisons between the various national situations; and lastly, the job classes and subclasses, which can be used to examine the forms and consequences of job segmentation. In addition to this package, there is also the Household PCS, another innovation included in the updating of the classification, which provides an alternative to using the reference person in order to study the social position of households (Box 2).

But users do not need just one package of social categorisations. In fact, while guaranteeing their reference frame, the updating of the classification has led to a complete rethink of the different detailed levels of the updated classification, with the standardised descriptions and their ad hoc groupings, the professions and groups of professions all creating an extensive tool kit for analysing job structure and work situations, supplemented by the main international classification (ISCO) and French classifications (the DARES’ FAP classification and the ROME register kept by the French employment agency, Pôle Emploi). So a second package of categorisations has resulted from the update, each with a preferred use:

- Descriptions of professions collected on a list, for investigations linked as closely as possible to working activities;

- The level of professions and groups of professions for structural analyses of the world of work;

- The FAP and ROME for studying the dynamics of the labour market;

- ISCO for international comparisons.

A new overall architecture thus emerges (Figure 2): still structured around its backbone, which interlinks with nested professions, socio-professional groups and categories, the classification is supplemented with both aggregate and detailed levels. The rigid connection between social and professional provided by the classification since 1982 is thus rendered flexible and new levels of analysis are offered: more detailed levels through the descriptions collected, mid-levels through the profession groupings (similar to micro-classes) and aggregate levels with the Job Class Schema.

Figure 2. New Architecture of the French Information System for Socio-Professional Situation

In parallel with these developments, other innovations have been adopted, technical this time, aimed at encouraging use of the classification.

Increasing Use Through a Simplified Coding Procedure...

While the history of the socio-professional classification has focused particular attention on its practical dimension (Desrosières and Thévenot, 2002; Desrosières, 2010), these works were mainly interested in the coding practices and the constraints these imposed on producers in terms of the clarity and simplicity of statistical categories. The broader question of the conditions for its users to appropriate the classification has received far less attention, other than in the one-off surveys carried out before the 1982 reworking and the 2003 and 2020 updates.

It was for that reason, and to reflect the wishes expressed when these surveys were being produced, that the group in charge of the latest classification update made the user central to their thinking and included greater use of the classification as one of their main objectives. They endeavoured to meet this objective not only by simplifying its production, thanks to a streamlined coding procedure, but also by facilitating its appropriation through a dedicated website.

The method followed up to now for coding the classification was initially established for past surveys in paper format. So it was based on the descriptions of professions as spontaneously declared or entered in plain text, and on a large number of items of so-called “related” information used to supplement the often incomplete descriptions and ultimately to allow a code to be obtained (automatically, through the SICORE-PCS environment or manually corrected). This method had its limitations: cost of gathering the data related to the number of associated variables and cost of correction due to the difficulty of coding imprecise descriptions. A new protocol was therefore produced, based on the possibilities offered by the development of digital tools and, in particular, “smart” search engines to allow searches using an auto-complete function when looking for a description in a list of thousands.

Thanks to an efficient data collection app (smooth completion process, including when self-administrated) and the drawing up of a comprehensive list of enhanced, standardized descriptions of professions, so they can all be coded, the expected volume of descriptions not found in the list (which will continue to be coded as at present) is low.

This development constitutes a noticeable improvement in that the information collected has a decisive effect on coding quality, regardless of the coding process envisaged. In addition, the number of “related” variables can be greatly reduced since they are now limited to status and size of company for independent workers, and professional position according to type of employer for salaried workers. The reduction in the number of variables needed for coding purposes is also accompanied by the simplification and standardization of their formulation, so as to allow better comparability with the codes obtained in different surveys, based on a “multi-mode” data collection approach.

This updated collection system is accompanied by a simplification of the coding procedure, thanks to a program following the matrix-based entry of information that allows a code to be allocated in a deterministic way to any couple (description and related variable). Consequently, the expected improvements do not just concern the professionals in departments that produce official statistics, who should see a reduction in collection costs and an improvement in coding quality. Another practical effect of the updated coding procedure will be documentation guides that are more accessible, notably a guide for viewing all the rules on allocation of the listed descriptions, in alphabetical order.

The provision of all these tools (description collection app, formulation of related variables, codification program and documentation guides) should thus allow a broader community of users (statisticians from polling institutes and research teams) to be able to simply obtain a quality PCS variable in the surveys they produce. Encouraging such use is one of the specific objectives of the future dedicated website for the classification.

... and Appropriation of the Classification thanks to a Dedicated Website

The overview of the situation and the consultations carried out as part of the updating process stressed the importance of having a digital space for information and discussion that, together with www.insee.fr, would enable all users’ expectations to be met.

Such a website is therefore expected to provide:

- information to help understand the history and key principles of the classification, and how it links with its counterparts in France and abroad;

- a browsing tool to be able to follow its logic more clearly and skim through the menu of its component headings and the aggregation methods it proposes;

- statistics for analysing and understanding society based on the socio-professional classification, from a selection of tables and charts to a micro-data search engine and with basic statistical analyses done online;

- the instruments needed to collect and code the classification, its various aggregates, as well as the international classification of occupations (ISCO) and European socio-economic categorisation (ESeG).

These are the precise objectives that have guided the design of the projected tree structure of this site, which is due to be set up gradually between 2020 and 2021. In principle, therefore, it will be organised under four main headings: Discover; Browse; Describe and Code. This is the result of a partnership between various institutions (INSEE, PROGEDO, the Printemps laboratory at the University of Versailles Saint-Quentin and CNAM-CEET), and is aimed at meeting all of the expectations of PCS producers and users, including members of the general public, journalists, representatives of organisations and unions, teachers, researchers and statisticians in both the public and private sphere.

In the end, following its latest update, the socio-professional classification offers greater clarity and greater flexibility of use. At the detailed level, its principles have been reaffirmed while its headings have been updated and supplemented with new analysis options. The same applies at aggregate level, where new analytical frameworks have been added to the historic categories. The simplification of the coding procedure and the dedicated website add the finishing touches to the whole project, resulting in the consolidation of the central position held by this iconic French official statistics classification.

Paru le :15/09/2022

These revisions prove necessary through the disconnect between real and statistical time dimensions, echoing the three time dimensions (relating to the law, databases and the real world) analysed by Isabelle Boydens (Boydens, 1999).

The recent updating of the PCS took the form of a working group from the National Council for Statistical Information (CNIS), who carried out the work in 2018 and 2019.

In the 17th century, in his fable called The Case of Conscience, La Fontaine describes Adam in the original French work as the “nomenclateur” in the section usually translated into English as “GOD, in his goodness, made, one lovely day, Apollo, who directs the lyric lay, And gave him pow'rs to call and name at will, Like father Adam, with primordial skill. Said he, go, names bestow that please the ear.”.

As a general rule these are backed by information systems, as in the case, for example, of the legal status of firms, recorded in the SIRENE register, or the classification of water use, which is linked to the water information system (SANDRE).

A classification in which the topographical and aetiological principles still remain interlinked today (following the addition of categories relating to external causes of mortality and factors influencing state of health).

CCAM: the French coding system for clinical procedures; CSARR: specific catalogue of physiotherapy and rehabilitation procedures.

LPP: list of products and services covered by French health insurance; ATC: Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System.

A rear-view mirror, for example, may be classified according to the main material from which it is made (the glass manufacturing sector) or its use (the vehicle equipment sector).

As Desrosières said, “it is necessary to come together to agree on what is understood to be equivalent, as equivalence is never a foregone conclusion” (Desrosières, 2014).

These surveys were conducted by Alain Desrosières in 1975, Hedda Faucheux and Guy Neyret in 1998 and Étienne Penissat, Anton Perdoncin and Marceline Bodier in 2018.

They are named after Alexandre Parodi, the Minister of Labour at that time, who introduced them in 1945.

Modifying the normative structures that the classification grids represent presupposes renegotiation of employees’ relative positions in the wage hierarchy in relation to one another, which can have a significant cost for companies in terms of balance and organisation.

Apart from the rewording of some titles to express the evolution in their composition and the prospect of their gender-neutral version.

International Standard Classification of Occupations, known as ISCO.

These “descriptions” correspond to the way respondents declare their occupation in statistical surveys: they are therefore job labels.

This standardization of head counts by profession according to gender corresponds with the dual move to group together professions that are declining in number, and splitting professions that are expanding, which are more often male-dominated and female-dominated, respectively (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAmossé, 2004).

Unlike the historic classification, it follows a logical, criterion-based construction and does not refer to the existing categories in the world of work.

A distinction is made between four qualification levels for professions undertaken as a salaried worker, based on a composite concept combining the educational qualifications required, the position held and the level of remuneration observed on average within the profession.

The Research, Studies, and Statistics Directorate (DARES), the French statistical Department of the Labour Ministry, has compiled the Professional Families classification (FAP).

ROME: Operational directory of trades and jobs used by Pôle Emploi to encode jobs sought by job seekers and job vacancies listed by companies.

The latest revision to the International Classification of Diseases followed the same approach, regarding ICD-10 as the nucleus of a “family” of classifications for covering other analytical purposes.

Status and number of employees in the company, professional position, nature of the workplace and also the business sector and role performed or, more exceptionally, gender for family workers and, for farmers, the type of farm, surface area of farmland used and region in which the farm is located.

SICORE is an automatic coding tool used for the last 25 years in French official statistics to code all kinds of descriptions in a given classification: PCS, NAF (the French classification of business activities), municipality codes, etc. (Rivière, 1995). The SICORE-PCS environment is the version used by INSEE to code the PCS in its household surveys.

Auto-completion or automatic completion is an IT function that lets the user limit the amount of information they enter and suggests potentially appropriate additions to the chain of characters the user has begun to enter.

As an initial estimate, it is in the order of a few percentage points in face-to-face surveys.

On this subject, following an international comparison carried out by INSEE in 2018, there was no algorithm or tool that appeared more effective than the SICORE environment at that time.

The development of “multi-mode” surveys (collecting data over the internet, by phone and face-to-face) and tools for designing questionnaires have, for example, led INSEE to simplify and standardize the questions (Cotton and Dubois, 2019; Koumarianos and Sigaud, 2019).

At the time of writing this article, all of the component elements of the documentation on use of the PCS 2020 are being produced.

PROGEDO (PROduction et GEstion des DOnnées – Data Production & Management) is a Very Large Research Infrastructure (TGIR) tasked with driving and structuring a public data policy for social sciences research.

The Centre for Employment Studies (CEET) is an overarching programme within the National Conservatory of Arts & Crafts (CNAM), aimed at developing multidisciplinary research into work and employment, from an academic perspective and to meet a social need.

Pour en savoir plus

AMOSSÉ, Thomas, 2004. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletProfessions au féminin : représentation statistique, construction sociale. In : Travail, genre et sociétés. [online]. Éditions La Découverte, 2004/1, n°11, pp. 31-46. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

AMOSSÉ, Thomas, 2013. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLa nomenclature socio-professionnelle : une histoire revisitée. In : Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. [online]. Éditions de l’EHESS, 2013/4, 68e année, pp. 1039-1075. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

AMOSSÉ, Thomas, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLa rénovation de la nomenclature socioprofessionnelle (2018-2019). [online]. December 2019. Rapport de groupe de travail du Cnis n°156. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

BOEDA, Michel, 2008. Les nomenclatures statistiques : pourquoi et comment. In : Courrier des statistiques. [online]. November-December 2008. N°125, pp. 5-11. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

BOLTANSKI, Luc et THÉVENOT, Laurent, 1991. De la justification. Les économies de la grandeur. 12 April 1991. Gallimard, Collection NRF Essais. ISBN : 978-2-07-072254-9.

BOYDENS, Isabelle, 1999. Informatique, normes et temps. Évaluer et améliorer la qualité de l'information : les enseignements d’une approche herméneutique appliquée à la base de données LATG de l’ONSS. 31 December 1999. Éditions Bruylant. ISBN : 978-2-8027-1268-8.

COTTON, Franck et DUBOIS, Thomas, 2019. Pogues, un outil de conception de questionnaires. In : Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 19 December 2019. N°N3, pp. 17-28. [Accessed 18 May 2019].

DESROSIÈRES, Alain, 1977. Éléments pour l’histoire des nomenclatures socio-professionnelles. In : Pour une histoire de la statistique. Insee, Journées d’études sur l’histoire de la statistique, 23-25 June 1976, Vaucresson, Contributions, tome 1, pp. 155-231.

DESROSIÈRES, Alain, 2010. La politique des grands nombres. Histoire de la raison statistique. 19 August 2010. Éditions La Découverte, collection Poche / Sciences humaines et sociales, n°99. ISBN : 978-2-7071-6504-6.

DESROSIÈRES, Alain, 2014. Prouver et gouverner. Une analyse politique des statistiques publiques. 3 April 2014. Éditions La Découverte, collection Sciences humaines. ISBN : 978-2-7071-8249-4.

DESROSIÈRES, Alain et THÉVENOT, Laurent, 2002. Les catégories socioprofessionnelles. 24 October 2002. Éditions La Découverte, collection Repères, 5e édition. ISBN : 978-2-7071-3856-9.

FAGOT-LARGEAULT Anne, 1990. Les causes de la mort. Histoire naturelle et facteur de risque. Éditions Vrin, Lyon, Collection Science, histoire, philosophie. ISBN : 978-2-7116-9611-1.

GUIBERT, Bernard, LAGANIER, Jean et VOLLE, Michel, 1971. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEssai sur les nomenclatures industrielles. In : Économie et statistique. [online]. February 1971. N°20, pp. 23-36. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

GRUSKY, David B. et SØRENSEN, Jesper B., 1998. Can Class Analysis Be Salvaged? In : American Journal of Sociology. [online]. March 1998. N°5, vol.103, pp. 1187-1234.

HÉRAN, François, 1984. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletL’assise statistique de la sociologie. In : Économie et statistique. [online]. July-August 1984. N°168, pp. 23-35. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

HUGRÉE, Cédric et DE VERDALLE, Laure, 2015. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletIncontournables statuts. « Fonctionnaires » et « indépendants » à l’épreuve des catégorisations ordinaires du monde social. In : Sociologie du travail. [online]. April-June 2015. Vol. 57, n°2, pp. 200-229. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

HUGRÉE, Cédric, PENISSAT, Étienne et SPIRE, Alexis, 2015. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLes différences entre salariés du public et du privé après le tournant managérial des États en Europe. In : Revue française de sociologie. [online]. 2015/1, vol. 56, pp. 47-73. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

MERON, Monique, AMAR, Michel, BABET, Charline, BOUCHET-VALAT, Milan, BUGEJA-BLOCH, Fanny, GLEIZES, François, LEBARON, Frédéric, HUGRÉE, Cédric, PENISSAT, Étienne et SPIRE, Alexis, 2016. ESeG = European Socio economic Groups. Nomenclature socio-économique européenne. [online]. February-March 2016. Insee, DSDS, Document de travail, n°F1604. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

KRAMARZ, Francis, 1991. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDéclarer sa profession. In : Revue française de sociologie. [online]. N°32-1, pp. 3-27. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

KOUMARIANOS, Heïdi et SIGAUD, Éric, 2019. Eno, un générateur d’instruments de collecte. In : Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 19 December 2019. N°N2, pp. 29-44. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

PENISSAT, Étienne, PERDONCIN, Anton et BODIER, Marceline, 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLa PCS et ses usages, état des lieux et défis. [online]. October 2018. Rapport de groupe de travail du Cnis n°151. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

RIVIÈRE, Pascal, 1995. SICORE, un outil et une méthode pour le chiffrement automatique à l’Insee. In : Courrier des statistiques. [online]. August 1995. N°74, pp. 65-69. [Accessed 18 May 2020].

THÉVENOT, Laurent, 1986. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLes investissements de forme. In : Les conventions économiques. [online]. Cahiers de Centre d’étude de l’emploi, n°29, pp. 21-71, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris. [Accessed 18 May 2020].