Courrier des statistiques N7 - 2022

Mixed-mode collection in household surveys: a modernised collection method and a more complicated process

With the introduction of the Internet as a new data collection mode and the increasing difficulties in contacting households, the evolution of surveys towards mixed-mode protocols has become a strong strategic orientation for official statistical offices. Many mixed-mode protocols are possible, making it possible to take advantage of the benefits of each collection mode depending on the constraints, the survey topic and the target populations.

However, such protocols tend to make the survey process more complex. Adaptations are necessary to guarantee the quality of the results: firstly, the questionnaire and its duration, then the definition of the collection protocol and finally the statistical processing of the data after collection. Through the efforts of standardisation and simplification that it imposes, in particular with the introduction of self-administered sequences, the evolution towards mixed-mode surveys constitutes a real paradigm shift for household surveys.

- Mixed-mode data collection, a paradigm shift for household surveys

- Box 1. Towards Mobile First design

- Collection modes that adapt to the context of each survey

- A multitude of mixed-mode protocols: competitive, sequential, combined...

- ... or integrated (for sensitive questions)

- Protocols that can be adapted to the pace of surveys...

- Box 2. The protocol choices made by different countries regarding European social surveys

- ... and adapted to the profile of the populations surveyed

- The questionnaire: the cornerstone of a successful mixed-mode survey

- Adjust the duration of the questionnaire in line with the most restrictive modes

- Box 3. Levers to increase participation in surveys

- The challenge of data aggregation...

- ... and correction modes that do not definitively remove all difficulties

- Box 4. Obtain the resources in advance that will be needed to correct collection mode errors subsequently

- Making mixed-mode collection an asset to improve survey quality

Protocols using multiple data collection modes (in person, by telephone, online, etc.) are not new in Official Statistics surveys. However, the proliferation of Internet use, the evolution of household practices in terms of communication and participation and the standardisation of data collection tools are profound changes that are favourable to the expansion of mixed-mode data collection in household surveys. This evolution has been keenly promoted within official statistical services since the 2010s and has recently accelerated in the specific context of the Covid-19 health crisis. More than ever, it is emerging as a strong strategic focus for Official Statistics. However, mixed-mode data collection complicates both data collection processes and data processing following collection, creating a risk of breaks in series. Beyond the opportunities that this paradigm shift offers for household surveys, it is important to identify the challenges that this transition poses to statisticians. The choices made in France are based on a consideration of international dimensions.

Mixed-mode data collection, a paradigm shift for household surveys

The mixed-mode nature of a survey relates to both the contact protocol and the collection protocol. The initial contact very often consists of a letter, although the collection is rarely carried out via a paper questionnaire.

In reality, however, we refer to a mixed-mode survey when the collection protocol involves the use of multiple information collection modes: in person with an interviewer, by telephone, online, etc.

Multiple parameters come into play when determining the appropriateness of mixed-mode data collection: the target population, the information available to reach it (the sampling frame and contact data) and the subject. Several Official Statistics surveys have thus been conducted in a mixed-mode manner for many years, e.g.:

- the household Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) (Technologies de l’information et de la communication) survey has been carried out online, by paper and by telephone since 2007;

- the French Labour Force Survey (LFS) now combines collection in person, by telephone (since 2003) and online (since 2021) depending on the date of collection;

- for the Living Environment and Security (Cadre de vie et sécurité – CVS) survey, carried out by INSEE in person from 2006 to 2021, part of the questionnaire is self-administered with the information being collected anonymously via headset, etc.

Over the past decade, INSEE has embarked on a series of experiments to assess the impact of the introduction of online collection in survey protocols. This increasing use of online collection leads to a fresh analysis of mixed-mode protocols. In fact, in Official Statistics surveys, online collection is rarely envisaged as the only collection mode and is viewed as more of a supplementary mode.

There are three reasons for switching to mixed-mode surveys.

The first reason is the downward trend in the response rate for household surveys, although the situation in France is less problematic than in other European countries (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLuiten et al., 2020). However, diversification of the ways of contacting people increases the chances of reaching them and, in principle, the collection rate, even though the response rate does not in itself constitute a definitive indicator of quality (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGroves and Peytcheva, 2008). Thus, recent work (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletCornesse and Bosnjak, 2018) has shown that mixed-mode surveys are of better quality in terms of representativeness and that surveys conducted exclusively online have low participation rates and significant selection effects.

Generally speaking, conducting surveys in person seems better than doing so by telephone and online in terms of the representativeness of certain segments of the population, particularly the least privileged or educated, immigrants, those with a poor command of the French language or those living in urban areas (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBuelens and Van den Brakel, 2010).

The development of household appliances and practices is also a favourable context for mixed-mode surveys. Over the last decade, the rate of households obtaining Internet access (hardware and subscriptions) has skyrocketed in France: Internet is now in common use. Such a situation now brings France more in line with countries with more long-standing Internet take-up, such as the Netherlands, the Nordic countries, the United Kingdom and Germany. The conditions are therefore increasingly in favour of using this mode to survey households. In addition, the expectations of the households themselves seem high: some of the households surveyed increasingly fail to understand why such a service is not available, given that recent advances in web-based administrative processes are highly visible.

However, some people only access the Internet via smartphone: over 60% of the population of Europe are able to access the Internet via mobile phone. This underscores the challenge of offering an interface and questionnaire designed from the outset for this type of media (Mobile first), the page format of which adapts in an ergonomic way (responsive design) (Box 1).

Box 1. Towards Mobile First design

With tablets and then mobile phones, the need to generate “agnostic” questionnaires, i.e. questionnaires capable of providing the best ergonomics possible regardless of the situation and device used, has become crucial, particularly for surveys of young people.

Indeed, it is impossible to prevent respondents from responding on their smartphone, though doing so often requires zooming and scrolling efforts by the respondent. However, if the ergonomics of the questionnaire are not adapted to smartphones, there is a high risk of lower quality completion: systematic responses, partial non-responses or abandonment of the questionnaire part way through.

The questionnaire and questions should therefore be as short as possible and minimise the scrolling effort (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletCouper and Peterson, 2017). The use of “radio buttons” (or option boxes) is also recommended, adapting their size to the small screen and making the entire option selectable (not just the radio button). These authors even encourage switching to open-ended questions rather than long lists of options.

The most recent data indicate that when a survey is designed appropriately for smartphones, the quality of the data can be as good as that of data from online surveys completed via a desktop computer (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAntoun et al., 2017). There is therefore a strong incentive to adopt an approach of optimising questionnaires for mobile devices, particularly smartphones.

Notes: Mobile First is a web design concept optimised for mobile devices that goes beyond responsive web design. It consists of designing a site by prioritising the mobile version and gradually adapting the web design for larger screens, in contrast to the approach that was previously most widespread, which was to gradually downgrade a website to adapt it to display on a mobile phone.

Telephone surveys however, which have been used widely in the 1990s by polling institutes and part of Official Statistics, are now faced with lower participation rates, due to the weariness caused by incessant sales calls by phone. Landline telephones, which were the basis of such surveys until the 2010s, are now a tool that is very rarely answered (or connected) by new generations.

Budget constraints also generate an interest in the costs associated with the various collection modes: interviews with interviewers (in person or by telephone) are the most expensive and it is preferable to use them only for subjects or populations for which their experience is essential.

Given that each collection mode has its strengths and weaknesses in terms of coverage and selection bias, it is important to take advantage of the benefits that each of them offers when developing survey protocols.

Collection modes that adapt to the context of each survey

The analysis of measurement bias – i.e. of the impact of the collection mode on the response to surveys – contrasts self-administered methods (paper and online) and the modes involving interviewers (in person and by telephone). The two main forms of bias caused by the presence or absence of an interviewer are social desirability and satisficing:

- social desirability refers to the fact that some respondents may be led to provide a response that provides a rewarding image of themselves or that they believe meets normative expectations. It occurs more frequently during interviews by an interviewer and for questions concerning opinions or sensitive or intimate questions, such as the use of alcohol or illegal drugs (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBeck and Peretti-Watel, 2001) or sexual behaviours (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLegleye and Charrance, 2021);

- satisficing bias refers to the fact that some respondents are not willing to put in the effort to provide the optimal answer (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletKrosnick, 1991). This phenomenon occurs more frequently with self-administered, difficult, lengthy or repetitive questionnaires for which levels of concentration and commitment are lower than in the presence of an interviewer. It can take the form of providing approximate answers, a tendency to give preference to selecting the first options provided (primacy effect) or the most recent options provided (recency effect), a failure to refer to documents, the rounding of answers involving figures, the selection of average answers, a partial failure to respond or even the abandonment of the questionnaire. The lower level of concentration associated with self-administered modes means that they require significantly less time than interviews by telephone and this reduction in time need is accentuated further in the case of in-person interviews.

Furthermore, self-administered survey modes suffer from lower response rates and a greater risk of self-selection relating to the subject of the survey, given that responding requires a more pro-active approach by respondents.

These effects may vary depending on the characteristics of the respondents. Thus, for the most highly educated young people, people with digital skills and an interest in the digital world, responding online may seem perfectly natural: their responses via this mode are unlikely to be affected by satisficing. Conversely, these populations may be more difficult to interview by telephone or in person and their responses may be affected by a high level of social desirability in the presence of an interviewer. Furthermore, the contact details available vary: while the postal address is known for all households, this is not always the case for the mobile or landline phone numbers and the email address. The availability of these different contact details differs throughout the population, together with the ability to effectively contact people and their appetite to respond via the different collection modes.

A study conducted among a population of migrants thus showed that paper was the most appropriate mode for men and the telephone was most suitable for women – particularly to limit the impact of their partner’s presence (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletKappelhof, 2015).

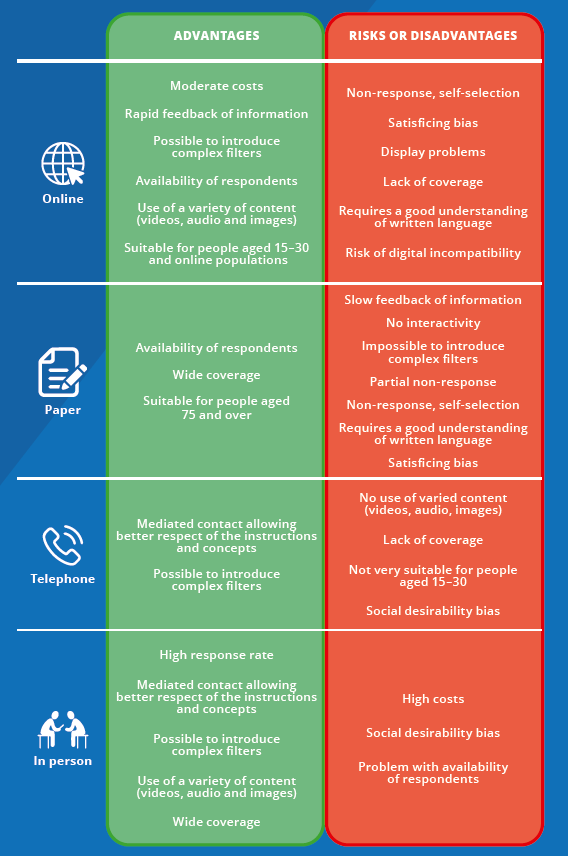

Each mode therefore has its advantages and disadvantages, depending on the subject, the target populations and the contact modes available (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Each collection mode has its own characteristics

A multitude of mixed-mode protocols: competitive, sequential, combined...

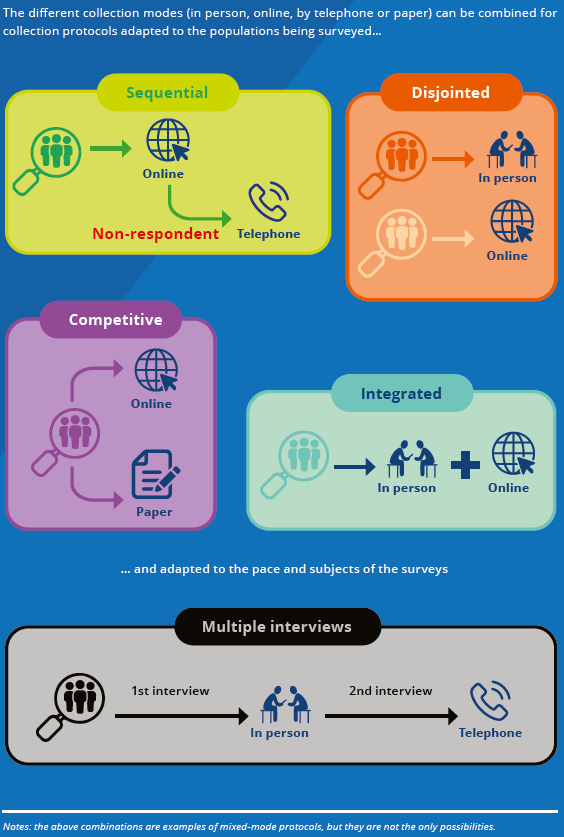

Protocols created on the basis of the different possibilities offered by the collection modes take very different forms (Figure 2).

The different collection modes can be proposed to respondents at the same time, with the modes being placed into some form of competition (this is referred to as a competitive mixed-mode protocol), or they can be proposed successively, with an alternative being proposed only to non-respondents in the previous phase (this is referred to as a sequential mixed-mode protocol). Generally speaking, a sequential mixed-mode protocol involves proposing the least costly collection modes first.

Most protocols result in a period in which several modes are competing: this is the case with sequential online/telephone protocols for which the ability to respond online remains available even when the telephone survey phase has begun. This is referred to as a combined protocol.

Figure 2. With mixed-mode protocols, data collection is becoming more flexible

The main limitation of the sequential protocol is that it makes some respondents respond

using a mode that is not their preferred mode and that this could degrade the quality

of their responses (a sensitive subject, an aversion to the mode, etc.). It also generates

a risk that respondents who would have agreed to respond if they had been approached

by an interviewer in the first place will find themselves in a worse disposition when

such contact is made after they have first refused to respond via a self-administered mode of collection: persistence with their initial refusal, marked

reluctance to make the necessary efforts to ensure the quality of the answers, etc.

Furthermore, the sequential protocol imposes a minimum collection time at each stage,

without which the chances of success of each mode are diminished. A short period of

field time is therefore an incentive to propose a competitive or combined mixed-mode

protocol rather than a sequential mixed-mode protocol.

However, generally speaking, the sequential mixed-mode protocol is considered most effective, particularly in financial terms (Dillman et al., 2014). In addition, leaving the choice of response mode to the respondent can be perceived as an additional cognitive burden (Schwartz, 2005), at a time when the respondent is often waiting for the interviewer, or the protocol if there is no interviewer, to guide them to allow them to complete the task as quickly as possible. Leaving the choice of response mode to the respondent is particularly interesting in panel surveys or with re-interviews, as the respondent can express their preference at the end of the first round of interviewing and provide their contact details, facilitating the use of a particular mode in subsequent rounds.

... or integrated (for sensitive questions)

An integrated mixed-mode protocol refers to the use of an additional collection mode during the collection for all respondents. This is the case, for example, when an interviewer in the home allows the respondent to answer part of the questionnaire on a computer alone, as in the case of the CVS survey, where they can use a headset and answer alone via the keyboard.

This type of protocol seems particularly well suited to sensitive questions (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletTurner et al., 1998). It undoubtedly makes it possible to take advantage of the different modes requested, but it is generally the most expensive.

In surveys conducted via telephone, it is also possible to request a switch to fully completing the questionnaire online (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLegleye and Charrance, 2021). For a series of sensitive questions, it is possible for the interviewer to be replaced by Interactive Voice Response (IVR), with which it is hoped that social desirability bias will be reduced (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletKreuter et al., 2008). This leads to quite a number of people abandoning the questionnaire during collection, as the experience is probably not considered very pleasant by respondents who lose the motivation caused by the audible presence of the interviewer and may result in the respondent not continuing with the questionnaire. It therefore seems preferable to use this collection mode only for short series of questions.

Protocols that can be adapted to the pace of surveys...

In longitudinal surveys, it is possible to adapt the collection modes to the different rounds of interviewing. The presence of an interviewer is often necessary to start the collection process. In contrast, subsequent rounds of interviewing (re-interviews) can often be carried out using less costly and less invasive collection modes, such as via telephone or online. In France, the Labour Force Survey and the Rents and Charges Survey (enquête Loyers et Charges) have been based on this type of protocol for many years now, combining an initial round of interviewing in person, followed by re-interviewing via telephone before the end of the process in-person. Since January 2021, a sequential online/telephone mixed-mode protocol is proposed for re‑interviewing related to the Labour Force Survey (Guillaumat-Tailliet and Tavan, 2021).

There are also two-phase protocols based on a double survey. The first phase entails a short survey conducted among a very large number of people, based on questions aimed at identifying a population of specific interest (people with disabilities, victims of violence, sexual minorities, etc.). Given the size of the sample, it may be advantageous to implement a sequential mixed-mode protocol using the less costly collection modes: online, then paper, then potentially telephone, for some of the non-respondents. The second phase, which can also use a mixed-mode protocol, is carried out among a selection of respondents from the first phase, in which certain characteristics of interest are over-represented thanks to the information from the filter survey. It can also use a mixed-mode protocol. Such a protocol was successfully adopted for the Everyday Life and Health/Autonomy (Vie quotidienne et santé (VQS)/Autonomie) survey of the Directorate of Research, Studies, Evaluation and Statistics (service statistique du ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé – DREES) and for the Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGender and Security (Genre et Sécurité – GENESE) survey by the Ministerial Statistical Department for Internal Security (SSMSI) of the Ministry of the Interior.

Finally, the increasing market penetration of smartphones now offers researchers the ability to collect data from smartphone users through passive data collection through the phone’s application use and history (geolocation, physical movements, online behaviour, etc.). Some of the collection can even be done on a smartphone (a diary or short questions at regular intervals, for example). This opportunity should not conceal the difficulties that some respondents face when they download an application to their smartphone or the challenges raised in relation to their consent to the collection and use of such data.

Ultimately, the constraints of each survey project may lead designers to focus their choices among the possibilities mentioned above (see the choices made for certain major European surveys in Box 2).

Box 2. The protocol choices made by different countries regarding European social surveys

As part of the European Mixed Mode Designs in Social Surveys (MIMOD*) project, led by the Italian statistical institute ISTAT from January 2018 to April 2019, a questionnaire concerning a few major European social surveys was conducted to establish the current situation in relation to mixed-mode data collection.

The majority of countries now conduct mixed-mode surveys, which was not yet the case five years ago. There appears to be a great deal of variety in relation to the protocols and, for the time being, the majority (57%) do not include an online collection mode.

According to experts in each country, some surveys seem to be more suited to collection online. For the first interview of the Labour Force Survey, it is the absence of the interviewer that appears to be the most damaging, while for that of the SRCV** surveys, it is the length of the questionnaire. The vast majority of the rounds of re-interviewing are identified as compatible with online collection, particularly those of the Labour Force Survey.

Of course, national contexts are sometimes key when determining structure: the availability of population registers in the Nordic countries, for example, can significantly reduce questioning when certain information is contained in such registers, which encourages the use of online collection. The countries that rely heavily on the telephone have connected systems that allow the retrieval of paradata (number of attempts, date and time of each attempt, etc.), even when the interviewers call from their homes, using virtual telephone platform systems.

*All the reports of the various working groups are available on the ISTAT website

(Ouvrir dans un nouvel onglethttps://www.istat.it/en/archivio/226140).

**Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (Statistiques sur les ressources et conditions de vie). The EU-SILC statistical system is intended to enable the production of structural indicators on the distribution of income, poverty and exclusion that are comparable across the European Union Member States.

... and adapted to the profile of the populations surveyed

These different types of mixed-mode protocols may not apply in the same way to all sampled units in a single survey. Thus, in recent years, protocols allowing the adaptation of the data collection strategy to the socio-demographic profile of the respondents have been designed and are now beginning to be implemented (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletChun et al., 2018). Adaptive design thus uses the information available prior to data collection in order to select the collection mode that, in principle, is the most effective for each unit surveyed, whether in terms of response rate or limitation of measurement bias.

For example, in the case of surveys on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use, sex and age appear to be dividing characteristics in terms of choosing the collection mode (self-administered or via telephone) (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBeck et al., 2014). One of the differences between adaptive design and the other forms of mixed-mode protocols is that the preference for a particular mode is fixed from the outset by the designer (as opposed to competitive mixed-mode protocols in which the respondent makes the choice) and that it is assumed (such a mode is better suited to such a sub-population).

Given that the length of the questionnaire is a factor that limits interest in the use of the Internet, it is also possible to target a population with a good ability to respond online without any degradation of quality (young people, from households of 1 or 2 people, who therefore do not have an overly complex household to describe), while the rest of the population is interviewed via telephone or in person.

There are also more complicated protocols involving the use of the information available during collection (data collected by questionnaire or obtained from paradata) to adjust the collection strategy for the rest of the sample: this is referred to as responsive design. It may thus be decided, during the collection, to focus efforts on a particular profile by targeting it directly or indirectly via a specific collection mode. Before being used in French Official Statistics surveys, this type of protocol would need to be tested to assess its appropriateness.

The questionnaire: the cornerstone of a successful mixed-mode survey

The implementation of a mixed-mode protocol requires that all stages of survey design and production be adapted to provide an ergonomic approach that minimises the effects of the mode. This effort is greatly facilitated by tools for the design and generation of collection media based on active metadata.

The first challenge is to adapt the questionnaire to the different modes envisaged: should we go all out to retain the same structure and the same questions for all modes or, instead, should we try to do the best we can in each mode? International recommendations strongly support the first solution (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDe Leeuw, 2018), although the most recent work calls for a third way seeking to optimise each questionnaire while minimising differences between the different modes.

This omni-mode (or agnostic) approach, which is used by multiple national statistical institutes (e.g. the Netherlands and the United Kingdom), consists of designing the questionnaire independently of the collection mode and then making the necessary adaptations in each mode, so as to minimise the mode effects. The main recommendations in this area are:

- adopt an omni-mode approach: the questions should not be linked to a specific mode;

- stick to one question per screen so that the respondent remains focused on one question at a time, unless they are filter questions or tracking questions;

- repeat the texts of the questions on the next page to provide the full stimulus again;

- always include all answer options on the screen in questions to be read aloud by interviewers;

- avoid tables and grids and give preference to a series of questions in all modes;

- minimise instructions and explanations and present them in a similar manner in the different modes.

The necessary adaptations include choices regarding graphic charts, the size and position of buttons/tick boxes and whether the “don’t know”/“do not want to answer” options should be shown always, only for a second attempt or never.

Generally speaking, the switch to mixed-mode protocols, particularly the introduction of self‑administered collection, is a good opportunity to re-examine what it is that the protocol is attempting to measure and to thus review the complications that may have been introduced over the various editions of surveys. If comprehension of the concepts and questions is reliant on the interviewer, it may not be passed on to the respondents themselves, which risks non‑response or incorrect answers.

The use of self-administration thus requires the use of simple question formulations and the provision of examples to provide clarification for respondents, particularly those among the general population, given that no rephrasing or guidance can be provided by the interviewer (Koumarianos and Schreiber, 2021). The way in which instructions, guidance and examples are presented must be considered on an ad hoc basis, to ensure that they are presented in an attractive and appropriate manner. Interviewers perform an important task of checking the information entered and compliance with the instructions during the switch: when the interviewers are absent, all this verification work is transferred to the statisticians in charge of data clearance, with a significant risk of error due to the inability to ask for clarifications regarding the information entered after the fact.

Adjust the duration of the questionnaire in line with the most restrictive modes

Responding to a survey is always a difficult exercise; however, participation in a survey and the quality of the information collected depend on the length and complexity of the questionnaire. While the presence of an interviewer, particularly in person, opens up possibilities for long and complex questions, self-administration, in contrast, very quickly comes up against the limits of what the least literate section of the population, or the section least interested in or affected by the subject, can or want to accomplish. Beyond a certain length of time that depends on the collection mode, the risk of satisficing increases, along with the risk of random answers, abandonment, increased use of “don’t know”, shorter responses to open questions and an overall decline in quality (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGalesic and Bosnjak, 2009). In the case of mixed-mode surveys, the length of the questionnaire is determined by the collection mode that generates the most constraints for the respondent.

The maximum recommended duration for telephone surveys is around half an hour (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletRoberts et al., 2010), but the presence of an interviewer often leads designers to exceed this limit, though they usually do not exceed three quarters of an hour. For online surveys, it is highly recommended not to exceed 20 minutes, with the ideal being a questionnaire with a median response time of 10 minutes (Revilla and Ochoa, 2017).

There are several possible solutions to limit questioning time if reducing the questionnaire is insufficient. The first is to administer the questionnaire in several sessions, which is like “panelising” the survey. This is not without risk or cost: attrition, management of household moves or breakdowns, extension of the reference period, complication of the statistical operations after collection, etc. Adaptive design protocols seek to address these problems by adjusting the questionnaire so that each respondent has an optimal questioning time from the point of view of the quality of the information collected. Thus, it may be the case that not all respondents are asked every question, but instead a common core of questions is determined and then different blocks of questions are randomly allocated to several sub-samples (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBeck and Richard, 2013). The matter of financial incentives, in the case of more difficult or longer questionnaires, is raised in Box 3.

Box 3. Levers to increase participation in surveys

According to the theoretical work of (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGroves et al., 2000) on the determining factors of participation in a survey, acceptance is influenced by: the nature of the body sponsoring the study, the respondent’s ability to use a smartphone, the duration of the data collection period, etc.; however, acceptance is above all influenced by the use of an incentive.

The international studies carried out over the past two decades have shown that a financial incentive is the most effective way to increase participation in household surveys (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSinger and Ye, 2012; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEdwards et al., 2009), rather than “gifts”. In particular, incentives are used by some statistical institutes where the burden on respondents is particularly heavy (due to the complexity or duration of the questionnaire), for example when the individual or household is asked to participate in a panel or when the duration of the questionnaire exceeds three quarters of an hour. They help to limit attrition. We note that experiments of this kind are rare in France (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLegleye et al., 2014; Ouvrir dans un nouvel onglet2016) and that their implementation by an Official Statistics body, for surveys that are mostly compulsory, raises questions of several kinds, particularly budgetary (increased cost) and ethical (for example: should civic participation in projects of social interest be monetised? Is there a breach of equality when targeting particular sub-populations? Should compensation be extended to all surveys? etc.). Such a decision complicates production procedures and requires a strict assessment (balance between cost and effectiveness in terms of representativeness or increases in variance or bias). Finally, long-term effects could arise: damage to the image and reputation of institutes; assessment of the importance of a survey based on the compensation provided for responding to it could lead to inter-survey competition and an upward trend in compensation, etc.

The challenge of data aggregation...

In mixed-mode surveys, the aggregation of data from different collection modes requires certain precautions. Indeed, that which is observed via one collection mode may not be directly comparable to that which is observed via another mode. This difference is called a mode effect. It can be broken down into two parts:

- selection bias: a given collection mode may lead to under-representation of certain categories of the population, as the likelihood of them responding depends on the mode proposed to them. Thus, the composition of the respondents differs from one collection mode to another, such that the average of the variables of interest is affected: this is called composition bias or selection bias;

- measurement bias: a given collection mode can lead to answers different to those provided via other modes, as the survey situation will influence the way respondents answer (social desirability, satisficing, memory bias, difficulty in dealing with a long list of items in self-administration or on the telephone, etc.). Measurement bias is the direct consequence of the collection mode on the response of a given individual (or similar individuals, given that the response of a single individual via two different collection modes is rarely observed).

The existence of selection bias stems from one of the objectives of mixed-mode surveys, i.e. from increasing the ways for respondents to respond. It is not in itself a problem, provided that there is no measurement effect and that the set of respondents, regardless of the mode of collection they use, is representative of the target population.

It is therefore important to neutralise all composition biases in order to properly assess that which is exclusively due to the collection mode, i.e. to assess the measurement bias.

To do this, modes are used that make it possible to render those responding via each collection mode perfectly comparable. In practice, however, it can be difficult to distinguish between the biases resulting from these two effects, selection and measurement (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletKlausch, 2014). Indeed, all of these modes are based on the strong assumption that there is no non-ignorable selection bias, i.e. an unobserved factor that influences both participation and the value of the variables of interest and which has little correlation with the observed factors for which controls are implemented (Rubin and Little, 2002). In such a case, particularly complex endogenous selection problems occur that are difficult to handle (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLee, 2009; Castell and Sillard, 2021; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletHeckman, 1979).

Work carried out on different data sets from French surveys has made it possible to determine the differences between the values obtained by reference surveys conducted in-person and online asking the same questions (Razafindranovona, 2015). These differences are lessened by taking socio-demographic characteristics into consideration and can be lessened further if the control variables are enriched by survey variables that are directly related to the subject of the survey.

However, a residual difference may remain, reflecting both a measurement bias and a composition bias on non-observable variables, such as interest in the subject of the survey (endogenous selection bias).

... and correction modes that do not definitively remove all difficulties

Collection mode effects are undoubtedly the most powerful constraint on the development of mixed-mode surveys: they complicate analyses, make it difficult to estimate the “true” levels of the survey’s indicators of interest and can lead to breaks in series. Estimating and correcting these biases requires assumptions to be made. To ensure the plausibility of these assumptions, specific resources must be available, which must be considered prior to collection (Box 4).

Box 4. Obtain the resources in advance that will be needed to correct collection mode errors subsequently

Analysis of measurement effects requires the assumption that there is no non-observable composition bias between respondents via different collection modes and that each respondent via one collection mode will find a comparable individual among respondents via the other mode. There are solutions available to ensure the closest possible alignment with these assumptions, but they must be thought out in advance of the collection operations.

- An initial method involves having a disjointed control sample, on which the survey will be conducted via one of the mixed-mode sample collection modes. Ideally, the protocol dedicated to this sample should not only be based on the reference mode for the subject of the survey (i.e. leading to minimal measurement bias) but should also maximise the collection rate, which is often difficult. In the event of a trade-off between reducing measurement bias and maximising the collection rate, preference should be given to the collection rate, so as to obtain a sample containing all the profiles to be compared in each collection mode. This method can therefore be widely applied to multiple sub-samples, resulting in several different combinations of collection methods.

- Another method, which supplements the first, is to add relevant questions directly to the questionnaire. These questions should make it possible to ensure comparability between respondents via each of the collection methods in a more robust way than with the information available in the sampling frame or with conventional socio-demographic variables. For example, they may relate to the uses of different collection methods. It is important, however, that these variables are not themselves subject to measurement effects.

These methods are effective, but there is always a risk that profiles of specific respondents will have very little representation via one collection mode, making it difficult to assess and correct measurement effects. In addition, the effects can vary from one sub-population to another, which can greatly complicate the analysis.

- Another method, which performs particularly well, involves re-interviewing the same individuals, with a certain delay, via two different collection methods. The test is based on the strong assumption that the responses provided via the second mode are not affected by the earlier participation in the first method. In so far as the situation created by this protocol is very artificial, it is necessary to take particular care regarding contact with the respondent. It is also recommended that changes be made to the questionnaire, replacing the least important questions with didactic efforts to justify this fresh interview (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletKlausch, 2014).

- Another solution involves randomly assigning a collection method after obtaining agreement to participate, obtained following an initial request (ideally made via a different mode of contact than the collection methods tested). Estimates are then free from bias (on the sample of respondents) if the post-agreement response rate reaches 100% (which is unlikely). However, this method typically allows control of the two selection phases (one relating to the survey and the other relating to the method), which increases its reliability in relation to a conventional mixed-mode protocol.

The MIMOD project (Box 2) has made it possible to identify the modes specifically used in national statistical institutes to aggregate data from different collection modes and to update the knowledge gained on mixed-mode surveys. While there is beginning to be a wealth of experience in measuring the effects of collection modes shared among European countries, experience in correcting such effects remains rare, as does scientific literature on the subject.

There are several possible correction modes, but they remain bound by strong limitations, hence the most commonly taken option of not correcting for collection mode effects.

First, measurement bias is conceptually a problem at partial response level (compared to selection bias which is a problem at complete response level). In this respect, it can seem like a missing-value problem: it is thus effectively processed by imputation. However, this method constitutes a strong methodological, or even ethical, choice as it changes the responses of the respondents. Instead, “parsimonious” methods are given preference, selecting the observations with the most bias so as to minimise changes in the database (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLegleye et al., 2019).

Another method is to use calibration. This makes it possible to neutralise not only selection bias, but also measurement bias at aggregated level, by introducing constraints regarding the levels of the variable of interest. Thus, instead of changing the data, the weighting is changed so as to obtain the correct level in all or part of the sample. In contrast, measurement bias is not corrected at individual level. Again, margins will be given preference on the sub-populations with the most bias and the use of a control sample collected via a single mode is strongly recommended.

It is also possible not to correct the measurement bias, but to instead try to contain it in time: in repeated surveys, it is possible to introduce a constraint in the adjustment that maintains the shares of the different collection modes at constant values (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBuelens and Van den Brakel, 2010). This has the benefit of simplicity, but also raises questions of sustainability if a collection mode disappears or in the event of a change in the shares of the different collection modes over time.

Beyond measurement bias, it may be necessary to correct another bias: a non-observable selection bias affecting all respondents. This issue is not directly related to mixed-mode surveys which, on the contrary, can improve the representativeness of the survey, depending on the protocol. However, mixed-mode surveys are most often associated with the introduction of the Internet and the use of collection modes with a lower response rate and a lower representation of respondents than in person. In such cases, correction methods exist, based on Heckman’s approach (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletHeckman, 1979). However, their validity is based on the strong assumption that there is no measurement bias (Castell and Sillard, 2021) because, at present, there is no method that makes it possible to deal with both simultaneously if the choice to respond via a certain method is made by the respondent (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLee, 2009).

Generally speaking, the methods of correcting measurement effects require specific work to be carried out. Thus, not all variables in a survey can be analysed, let alone corrected. It is therefore important to carefully select the main variables of interest. Furthermore, the methods require the assumption that one of the collection modes constitutes the reference, either because it is the historical mode used by a survey series or because it is deemed to produce the best quality measurement. A quality control sample, collected via a single mode (or with embedded mixed-mode collection) is therefore often required.

Thus, the detection of collection mode effects may justify adapting the survey protocol and its sampling method, in particular to ensure that disjointed sub-samples can be collected in accordance with the compositions of the different collection modes (Box 4).

Making mixed-mode collection an asset to improve survey quality

The development of mixed-mode collection gives us an opportunity to reconsider the design of household surveys around fundamental and structural good practices, which guarantee a minimum quality of responses such as meeting a maximum response time for a questionnaire and the use of concepts and formulations that are understandable to the large majority of the population.

In its “mixed-mode collection” programme, INSEE has chosen to propose online as the sole option only in certain contexts (short or sequenced surveys, simple concepts and re-interviews following initial mediated contact). At a time when some polling institutes are abandoning in-person surveys and, in some instances, even telephone surveys, INSEE’s strength is that it has a network of interviewers who are highly experienced in terms of in-person interviews and are well spread throughout France.

Ultimately, the evolution towards mixed-mode data collection is indeed an opportunity to improve surveys in many respects; however, it also represents an organisational cost and a challenge in terms of managing collection mode effects: this should call for us to take greater care in the methodological choices considered when designing the survey. In view of the spread of mixed-mode data collection in Europe, it would be necessary, for example, to shift European regulations towards omni-mode questionnaires, which would have to be simplified compared with those currently in use which were designed in a world dominated by in-person data collection. In autumn 2021, an ad hoc working group (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEurostat, 2021) presented recommendations along those lines: a position paper (coordinated by France) identifies the fields of inquiry for the coming years (in terms of methodological and data collection issues) to adapt European household surveys to the context of mixed-mode data collection.

Paru le :19/02/2024

As regards the impact of mixed-mode data collection on the way in which the data collection is organised and the work of investigators, see the article by Éric Sigaud and Benoît Werquin on “The arrangement of mixed-mode surveys” in this issue.

The article is based, in particular, on the seminal work of Dillman et al. (2014) in the United States and that of Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDe Leeuw (2018) in Europe, as well as on an initial assessment of the situation performed in the context of French Official Statistics (Razafindranovona, 2015).

Very few household surveys still use paper (ICT survey), while some have even started to do so alongside the Internet (e.g. The Lived and Perceived Experience in relation to Security (Vécu et Ressenti en matière de Sécurité – Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletVRS) survey conducted by the Ministerial Interior Security Statistical Service (Service statistique ministériel de la sécurité intérieure – SSMSI)).

A survey of non-respondents to the LFS has been conducted since 2007 online and in paper format and its results have been incorporated into the weighting for the 2007 survey. See the article in Courrier des statistiques issue n°6 on the new data collection protocol for the LFS (Guillaumat-Tailliet and Tavan, 2021).

For example, the response rate has fallen for CVS surveys (from 72% to 66% between 2012 and 2021) and surveys on Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (Statistiques sur les Ressources et les Conditions de Vie – SRCV) (from 85% to 80% between 2010 and 2019) conducted in person.

Between 2007 and 2021, the rate of households with Internet access increased from 54% to 91%, while the daily or near-daily use rate increased from 36% to 72% (Household ICT Survey).

The article is based, in particular, on the seminal work of Dillman et al. (2014) in the United States and that of Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDe Leeuw (2018) in Europe, as well as on an initial assessment of the situation performed in the context of French Official Statistics (Razafindranovona, 2015).

Between 2007 and 2021, the rate of households with Internet access increased from 54% to 91%, while the daily or near-daily use rate increased from 36% to 72% (Household ICT Survey).

The response rate for the first round of the Monthly Consumer Confidence survey (Enquête mensuelle de conjoncture auprès des ménages – CAMME) fell from 63% to 53% between 2013 and 2020.

According to the 2021 ICT survey, only 66% of those aged 15 to 29 have a landline telephone: 42% answer all calls, 21% never answer and 23% answer only when they know the number making the call. By comparison, 99% of them have a mobile phone: 65% answer all calls, 2% never answer and 31% answer only when the number making the call is known.

This portmanteau word is a combination of satisfying and sufficing: it first appeared in 1957 in a speech by the sociologist, economist and psychologist Herbert Simon as part of his research into human behaviour.

IVR is used to support respondents and issue reminders or in automated mode asking the questions and collecting the answers. In relation to sensitive subjects, it provides better results than the telephone, though it does not reach the level of self-administered questionnaires, which remain the preferred method for reducing social desirability bias.

Information that is not targeted by the collection but that can be collected at the same time, such as: if a unit belongs to the sample, if it has responded, the number of attempts to contact it, the collection method, etc.

The notion of active metadata was discussed in issue no 3 of the review. See also the article by Éric Sigaud and Benoît Werquin also in this issue.

This may be the case with the feeling of insecurity reported in relation to assessing the effect of the collection method on victimisation rates or with a well-being score to assess the effect of the collection method on some working conditions, etc.

Pour en savoir plus

ANTOUN, Christopher, COUPER, Mick P. et CONRAD, Frederick G., 2017. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEffects of Mobile versus PC Web on Survey Response Quality: A Crossover Experiment in a Probability Web Panel. In : Public Opinion Quarterly. [online]. 28 March 2017. Vol. 81, n° S1, 2017, pp. 280-306. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

BECK, François et PERETTI-WATEL, Patrick, 2001. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLes usages de drogues illicites déclarés par les adolescents selon le mode de collecte. In : Population. [online]. 56e année, n° 6, pp. 963-985. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

BECK, François, et RICHARD, Jean-Baptiste, 2013. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLe Baromètre santé de l’INPES, un outil d’observation et de compréhension des comportements de santé des jeunes. In : Agora Débats Jeunesses. [online]. Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, n° 63, pp. 51-60. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

BECK, François, GUIGNARD, Romain et LEGLEYE, Stéphane, 2014. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDoes Computer Survey Technology Improve Reports on Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use in the General Population? A Comparison Between Two Surveys with Different Data Collection Modes In France. [online]. 22 January 2014. PLOS ONE. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

BUELENS, Bart et VAN DEN BRAKEL, Jan, 2010. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletOn the Necessity to Include Personal Interviewing in Mixed-Mode Surveys. In : Survey Practice. [online]. 30 September 2010. Vol. 3, n° 5. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

CASTELL, Laura, SILLARD, Patrick, 2021. The Treatment of Endogenous Selection Bias in Household Surveys by Heckman Model. [online]. 24 March 2021. Insee. Document de travail n° M2021/02. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

CHUN, Asaph Young, HEERINGA, Steven G. et SCHOUTEN, Barry, 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletResponsive and Adaptive Design for Survey Optimization. In : Journal of Official Statistics. [online]. September 2018. Vol. 34, n° 3, pp. 581‑597. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

CORNESSE, Carina et BOSNJAK, Michael, 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletIs there an association between survey characteristics and representativeness? A meta-analysis. In : Survey Research Methods. [online]. 12 April 2018. Vol. 12, n° 1, pp. 1-13. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

COUPER, Mick P, PETERSON, Gregg J, 2016. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletWhy Do Web Surveys Take Longer on Smartphones? In : Social sciences computer review. [online]. 11 February 2016. Vol. 35, n° 3, pp. 355-377. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

DE LEEUW, Edith, 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletMixed-Mode: Past, Present, and Future. In : Survey Research Methods. [online]. 13 August 2018. Vol. 12, n° 2, pp. 75-89. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

DILLMAN, Don A., SMYTH, Jolene D., CHRISTIAN, Leah Melani, 2014. Internet, Phone, Mail and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. August 2014. Éditions Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-45614-9.

EDWARDS, Philip James, ROBERTS, Ian, CLARKE, Mike J., DIGUISEPPI, Carolyn, WENTZ, Reinhard, KWAN, Irene, COOPER, Rachel, FELIX, Lambert M. et PRATAP, Sarah, 2009. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletMethods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. [online]. 8 July 2009. Éditions John Wiley & Sons. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, n° 3, article n° MR000008. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

EUROSTAT, 2021. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletPosition Paper on Mixed-Mode Data Collection in Household Surveys. [online]. 19 October 2021. Groupe de travail sur les enquêtes ménages en multimode. Projet présenté aux directeurs des statistiques sociales (DSS), aux directeurs de la méthodologie (DIME) et aux directeurs des systèmes d’information (IT). [Accessed 15 December 2021].

GALESIC, Mirta et BOSNJAK, Michael, 2009. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEffects of Questionnaire Length on Participation and Indicators of Response Quality in a Web Survey. In : Public Opinion Quarterly. [online]. 28 May 2009. Oxford Academics Journal. Vol. 73, n° 2, pp. 349-360. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

GROVES, Robert M. et PEYTCHEVA, Emilia, 2008. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletThe Impact of Nonresponse Rates on Nonresponse Bias: A Meta-Analysis. In : Public Opinion Quarterly. [online]. 7 May 2008. Oxford Academics Journal. Vol. 72, n° 2, pp. 167-89. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

GROVES, Robert M., SINGER, Eleanor et CORNING, Amy, 2000. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLeverage-Saliency Theory of Survey Participation: Description and an Illustration. In : Public Opinion Quarterly. [online]. 1er November 2000. Oxford Academics Journal. Vol. 64, n° 3, pp. 299-308. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

GUILLAUMAT-TAILLIET, François et TAVAN, Chloé, 2021. A new Labour Force Survey in 2021 - Between the European imperative and the desire for modernisation. In : Courrier des statistiques. [online]. 8 July 2021. Insee. N° N6, pp. 7-27. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

HECKMAN, James J., 1979. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSample Selection Bias as a Specification Error. In : Econometrica, Journal of the econometric society. [online]. January 1979. Vol. 47, n° 1, pp. 153-161. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

KAPPELHOF, Johannes W. S., 2015. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletFace-to-Face or Sequential Mixed-Mode Surveys Among Non-Western Minorities in the Netherlands: The Effect of Different Survey Designs on the Possibility of Nonresponse Bias. In : Journal of Official Statistics. [online]. March 2015. Vol. 31, n° 1, pp. 1-30. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

KLAUSCH, Lars Thomas, 2014. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletInformed Design of Mixed-Mode Surveys − Evaluating mode effects on measurement and selection error. [online]. 10 October 2014. Utrecht University − Department of Methodology and Statistics. ISBN 978-90-393-6192-4. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

KOUMARIANOS, Heïdi et SCHREIBER, Amandine, 2021. Conception de questionnaires auto-administrés. [online]. 15 December 2021. Insee. Document de travail n° M2021/03.[Accessed 15 December 2021].

KREUTER, Frauke, PRESSER, Stanley et TOURANGEAU, Roger, 2008. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSocial Desirability Bias in CATI, IVR, and Web Surveys: The Effects of Mode and Question Sensitivity. In : Public Opinion Quarterly. [online]. December 2008. Oxford Academics Journal. Vol. 72, n° 5, pp. 847-865. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

KROSNICK, Jon A., 1991. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletResponse strategies for coping with the cognitive demands of attitude measures in surveys. In : Applied Cognitive Psychology. [online]. May/June 1991. Vol. 5, n° 3, pp. 213-236. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

LEE, David S., 2009. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletTraining, Wages, and Sample Selection: Estimating Sharp Bounds on Treatment Effects. In : The Review of Economic Studies. [online]. July 2009. Vol. 76, n° 3, pp. 1071-1102. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

LEGLEYE, S., BOHET, A., RAZAFINDRATSIMA, N., BAJOS, N. et MOREAU, C., 2014. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletA randomized trial of survey participation in a national random sample of general practitioners and gynecologists in France. In : Revue d’Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique. [online]. August 2014. Vol. 62, n° 4, pp. 249-255. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

LEGLEYE, Stéphane et CHARRANCE, Géraldine, 2021. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSequential and Concurrent Internet-Telephone Mixed-Mode Designs in Sexual Health Behavior Research. [online]. 30 August 2021. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

LEGLEYE, Stéphane, RAZAFINDRANOVONA, Tiaray et DE PERETTI, Gaël, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAgregating mix-mode survey data: a practical approach to neutralize measurement bias. [online]. 19 July 2019. European Survey Research Association. Conférence internationale 2019, Zagreb. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

LEGLEYE, Stéphane, RAZAKAMANANA, Nirintsoa, CORNILLEAU, Anne et COUSTEAUX, Anne-Sophie, 2016. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletIntéressement financier, motivation initiale et caractéristiques des enquêtes : effets sur le recrutement et la participation à long terme dans le panel ELIPSS. [online]. 30 October 2016. Université du Québec en Outaouais. 9e Colloque francophone sur les sondages, Gatineau. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

LUITEN, Annemieke, HOX, Joop et DE LEEUW, Edith, 2020. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSurvey Nonresponse Trends and Fieldwork Effort in the 21st Century: Results of an International Study across Countries and Surveys. In : Journal of Official Statistics. [online]. 24 July 2020. Vol. 36, n° 3, pp. 469-487. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

RAZAFINDRANOVONA, Tiaray, 2015. La collecte multimode et le paradigme de l’erreur d’enquête totale. [online]. 27 March 2015. Insee. Document de travail n° M2015/01. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

REVILLA, Melanie et OCHOA, Carlos, 2017. Ideal and Maximum Length for a Web Survey. In : International Journal of Market Research. 24 October 2017. Vol. 59, n° 5, pp. 557-566.

ROBERTS, Caroline, EVA, Gillian, ALLUM, Nick et LYNN, Peter, 2010. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletData Quality in Telephone Surveys and the Effect of Questionnaire Length: a Cross-National Experiment. [online]. 9 November 2010. Institute for Social and Economic Research. Working Paper Series n° 2010-36. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

RUBIN, Donald B. et LITTLE, Roderick J. A., 2002. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 26 August 2002. Éditions John Wiley & Sons, Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. ISBN 978-1119013563.

SCHWARTZ, Barry, 2005. The Paradox of Choice − Why More is Less. 18 January 2005. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0060005696.

SINGER, Eleanor et YE, Cong, 2012. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletThe use and effects of incentives in surveys. In : The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. [online]. 26 November 2012. Vol. 645, n° 1, pp.112-141. [Accessed 15 December 2021].

TURNER, C. F., KU, L., ROGERS, S. M., LINDBERG, L. D., PLECK, J. H., et SONENSTEIN, F. L., 1998. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAdolescent Sexual Behavior, Drug Use, and Violence: Increased Reporting with Computer Survey Technology. In : Science. [online]. 8 May 1998. Vol. 280, n° 5365, pp. 867-873. [Accessed 15 December 2021].