Economic outlook - February 2021

Presentation

Conjoncture in France

Paru le :10/02/2021

The second lockdown brought household consumption down more than production

The publication of the national accounts for Q4 2020 was a stark reminder, if one were needed, of the uncertainty in making economic forecasts in the context of the health crisis. The various monthly business tendency surveys and high-frequency data from search engines, for example, provide useful pointers regarding changes in economic activity, but they are no substitute for “hard” data (turnover indices calculated from VAT, etc.) which are consistent within the framework of the national accounts.

Since the start of the crisis, taking into account the spread of the epidemic and the associated containment measures of course, economic activity has twice proved higher than expected: first in May-June, at the end of the first lockdown, when there was a stronger rebound than forecast, then in November-December, when ultimately the second lockdown penalised economic activity to a lesser extent than suggested by virtually real-time estimates.

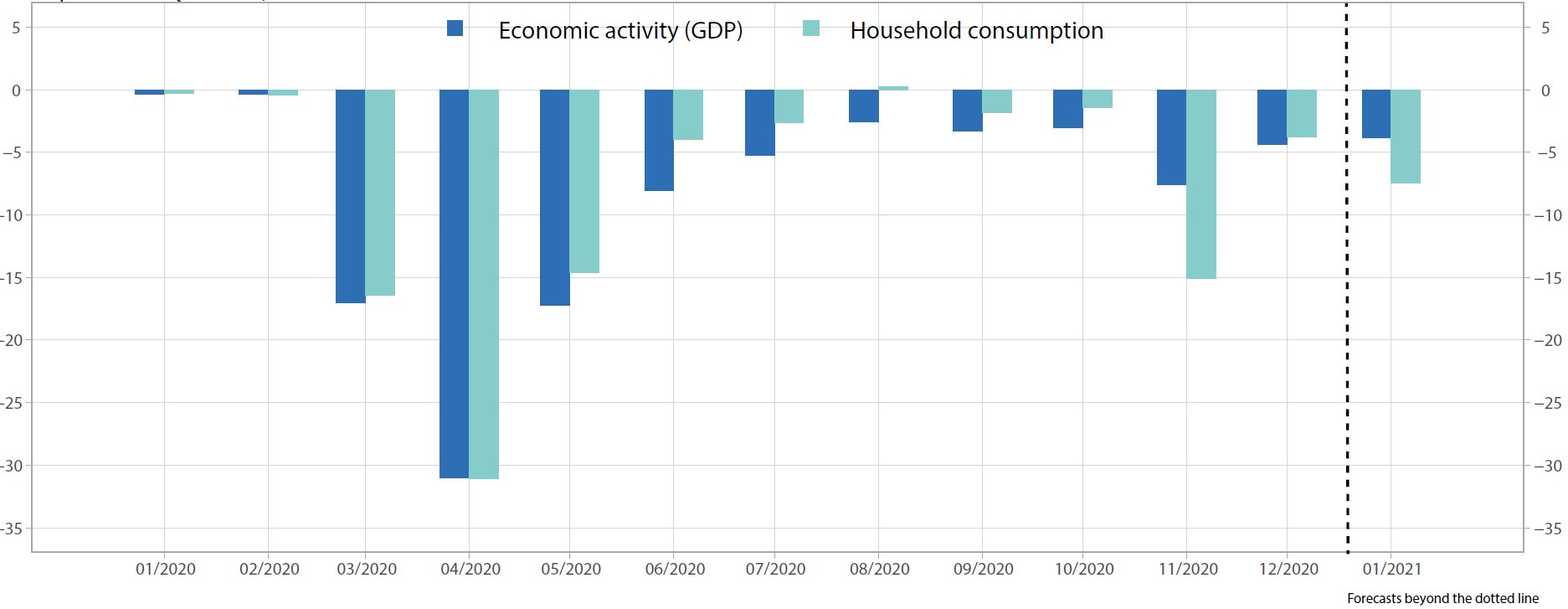

In November, the difference in GDP compared to its pre-crisis level will therefore have been around –8%, a considerable decline certainly, but only a quarter of that seen in April, before moving to –4% in December (figure). Industrial output was hardly affected at all, and services performed better than expected. The shock was to a large extent confined to the sectors most exposed to the restrictive measures: retail, leisure, accommodation-catering, transport. Investment and foreign trade held up better than expected.

However, household consumption tumbled almost as much as anticipated (–15% in November compared to its pre-crisis level), before rebounding strongly in December (–4% compared to its pre-crisis level). The high-frequency data used for this estimate (aggregated bank card transaction amounts, scanner data from major retail outlets) very closely track purchases of goods and services that directly make up part of household consumption, thus confirming their relevance.

graphiqueMonthly estimates and forecasts of GDP and household consumptiondifference compared to Q4 2019, in %

- Source: INSEE calculations and forecasting.

A mixed picture for January 2021, both on the economic front and the epidemic front

These same data suggest that household consumption is likely to be somewhat weakened during January 2021, moving back to 7% below its pre-crisis level. There are several factors that can account for this movement: December saw purchases made that had been postponed, given that “non-essential” stores were closed in November, but this catch-up phenomenon is unlikely to extend into January. In addition, the time of the curfew was gradually brought forward to 6pm for the entire country. Lastly, the shift in the dates of the winter sales may have meant that some January purchases were postponed from January to February.

The international environment also seems a little less buoyant at the start of the year, especially in Europe: the deterioration in the health situation in many countries has resulted in a tightening of restrictive measures. And possible changes in inventories in the United Kingdom at the end of 2020 just before Brexit could cause a backlash in January.

However, the business climate is stable in January compared to December. The various high-frequency indicators also suggest an overall stability in economic activity within the meaning of GDP, which would therefore seem to have maintained its December level in January (i.e. 4% below its pre-crisis level). Activity would seem to have remained on a plateau to some extent, rather like the epidemic: both have indeed evolved in tandem since the start of the crisis.

In the coming months, there will be no decline in uncertainty

Building precise forecasts beyond the month of January is currently something of a challenge. Just after the first wave of the epidemic, INSEE applied the expectations expressed in company surveys regarding the time needed to “return to normal”. This type of information is especially useful after a seismic shock that is unlikely to reoccur. However, the successive waves of the epidemic determine the recovery of the sectors most impacted by a return to normal of the health situation. And this seems to depend to a large extent on the ongoing race worldwide between the circulation of the virus and its variants on the one hand, and the vaccination campaigns on the other.

At this stage, all we can do is to sketch out some scenarios by way of illustration for the coming months:

- Assuming that activity in January is maintained in February then March, with no further tightening of the health restrictions, growth in Q1 2021 is likely to be around +1½%;

- Assuming a one-month lockdown in the next few weeks, with restrictions similar to those during the November lockdown, then growth would be zero (0%) in Q1;

- Finally, a lockdown of the same type as in November, but covering a large part of February and the whole of March, could lead to a further contraction in activity (of around –1%).

By assuming a return in Q2 to the level of activity reached in Q3 2020 (almost 4% below the pre-crisis level), according to the three scenarios given above, the annual growth overhang by mid-2021 would be between +4 and +5%.

In the short term, the effects of a possible third lockdown are at first difficult to predict: its impact would be closely dependent on the restrictions put in place, on its duration, and also on the ability of the economy to adapt (teleworking, development of digital technologies, etc.). In the slightly longer term, forecasting the situation in different sectors of activity is not straightforward: the first two lockdowns certainly demonstrated an ability to rebound in many sectors, helped by massive budgetary support. Regarding the sectors most affected, where activity remains restricted for the most part, uncertainties may be greater: a spring compressed for too long may not necessarily regain its original shape.

Alongside estimates of GDP and household consumption, this Economic Outlook includes two Focus reports:

- 2020 was marked by an unprecedented decline in economic activity (–8.3%), commented on extensively since the end of March in successive editions of Economic Outlook. This shock will probably have long-lasting consequences for employment, unemployment and income. Seen from a completely different perspective, this shock will have produced a temporary decline in greenhouse gas emissions generated by this economic activity. One Focus report sets out to quantify the temporary decrease in the carbon footprint of household consumption during the lockdowns (–36% in April, compared to its pre-crisis level), under the effect of both a decrease in consumption and, to a lesser extent, the change in its structure.

- The curfew was gradually extended to 6pm instead of 8pm during January, affecting a growing number of departments. A Focus study mobilises high-frequency data, especially the aggregated amounts of bank card transactions, to estimate the impact of this time change. When it was put in place, the extra 2 hours of curfew resulted in a decrease in bank card transaction amounts (excluding online sales) of around 6 to 7%, although it is not possible to infer what this impact might be if this measure were to last: it is likely that part of this effect is only transitory, while household behaviour adapts to these time restrictions.